Juilliard-trained cellist Christine Lamprea saw one of her biggest dreams come true last month: She had her first performance ever in Colombia, the country her parents left almost 50 years ago.

For five days, Lamprea, 26, joined Colombia's National Children's Symphony as a solo cellist. It was the first time she had ever visited Colombia and the trip helped her to realize the sacrifices her parents made in order to come to the United States and provide a better life for her and her siblings.

"I believe that my parents made the American Dream work for them. They came on their own and brought themselves up from their bootstraps," said Lamprea, who is currently a professional cellist with Astral Artists, a Philadelphia-based non-profit that helps develop the early careers of classical musicians.

Lamprea's father came to the U.S. in 1969 and her mother arrived a year later. They met at the Astoria Park Pool in Queens, New York and got married in 1972.

Her father, who arrived at age 20 dreaming of becoming an architect, ending up building a successful career in real estate. "My dad did it on his own. Now he's a salesman," said Lamprea.

Related: I want to bring health care to undocumented immigrants

Her mother arrived in the U.S. with her five siblings. She worked in a factory for five years, learned English at night and eventually became an accountant.

Lamprea was born in New York. But when she was seven, her parents moved the family to a predominantly English-speaking middle class neighborhood in San Antonio, Texas.

Many other relatives eventually moved to San Antonio as well and Lamprea grew up surrounded by her bilingual family members and immersed in Colombian culture. Yet, she didn't fully embrace her Latina identity, especially in her teenage years.

"I learned to dance Cumbia when I was little, was surrounded by Spanish, and was wrapped in the warm, generous spirit of my Latin family" she said. "But I had plenty of older cousins who were very Americanized and I moved in that direction. I didn't want to learn Spanish. English was the cool thing."

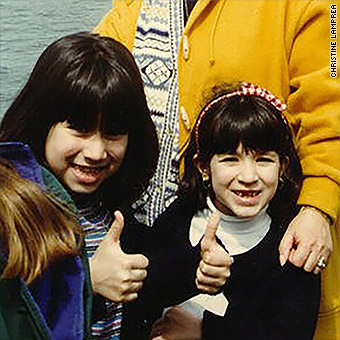

But her parents were able to influence both of their daughters when it came to music. As a result, Lamprea fell in love with the cello when she was 9 and her sister Stephanie became an aspiring opera singer.

In high school, Lamprea's first cello teacher recommended that she reach out to Ken Freudigman, the principal cellist of the San Antonio Symphony. "I played for him, and he agreed to take me on as a student. He pushed me very hard, and I owe him a lot," she said.

The summer of her junior year, she attended summer camp in Tanglewood, the classical music mecca outside of Boston and it changed her life.

"Being in a community where everyone loved music as much as I did inspired me to audition for a music conservatory," she said. "My teacher was surprised. He brought me in for two lessons a week instead of one and eventually I was accepted to The Juilliard School."

There, she studied under masters such as Bonnie Hampton, a protege of the great cellist Pablo Casals, and Itzhak Perlman, who even chose Lamprea to be his granddaughter's cello coach.

Related: My American Dream: Fighting for immigrant rights

After Juilliard, she pursued a master's from the New England Conservatory with the help of a fellowship. In 2012, she was awarded a Paul and Daisy Soros New Americans Fellowship which pays up to $90,000 for the graduate educations of 30 immigrants or children of immigrants.

At the time, Lamprea worried she wouldn't fit in with the other fellows. She was the only musician. The others were scientists, lawyers and activists. Plus, unlike many of the others, she didn't have a harrowing tale of overcoming poverty and she never felt like her status as the child of immigrants ever impeded her.

"I was asked, 'what's your immigrant story?' and I said 'I don't have an immigrant story,'" she remembers. But conversations with the other fellows opened her up to a different perspective.

Previously, she felt that her work ethic was simply part of her personality. Now she realizes it was heavily influenced by her parents.

"In so many of the anecdotes other fellows shared from their upbringing I found something similar had happened in mine, but simply disregarded its importance," she said. "It made me more conscious of how much of my life is influenced by my parents' and grandparents' journeys."

Related: Daughter of immigrants challenges the American Dream

The trip to Colombia reminded her of how tough life still is for many who remain in the country and the resilience that immigrants must have when they leave their homelands in pursuit of their dreams.

"After seeing that, I think there are more opportunities in America, even if it is more difficult now, it's still much better," Lamprea said.