Plastic products are ubiquitous -- from your sunglasses, toys and water bottles to your smartphones, tablets and even circuit boards.

What happens when these products are discarded?

The ideal scenario would be that it's all recycled. The reality is that a lot of it ends up in landfills.

Plastic isn't biodegradable, but it does decompose. As it breaks down, the polycarbonates used to make plastic products release BPA, an industrial chemical that can eventually leach into the environment.

Scientists at IBM (IBM) have figured out a way to repurpose this plastic so that it doesn't release BPA.

Related: This company has turned 4 billion plastic bottles into clothes

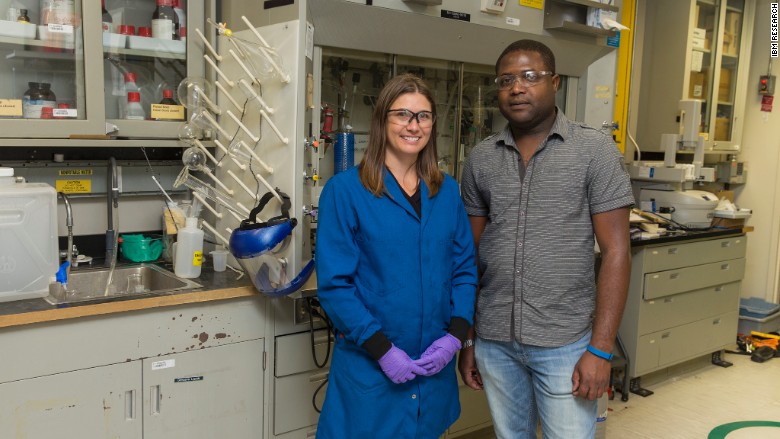

The process is fairly simply, and that's where the breakthrough has occurred, said Jeannette Garcia, a polymer scientist with IBM Research's Almaden lab in San Jose, California.

For the past four years, Garcia has been working on ways to sustainably recycle polymers.

"Polycarbonates get a bad rap because of BPA," said Garcia.

More than 2.7 million tons of polycarbonate plastic is produced each year, which goes to manufacture all kinds of everyday products.

It's the structure of polycarbonates that allows the polymer to leach BPA over time.

So Garcia and Gavin Jones, a fellow researcher in the Almaden Lab, figured out how to reconfigure it.

Related: She's recycling carbon dioxide into fuel

"We took apart the polymer, introduced new elements into it and recycled it into a new type of plastic that locks in the BPA," she said.

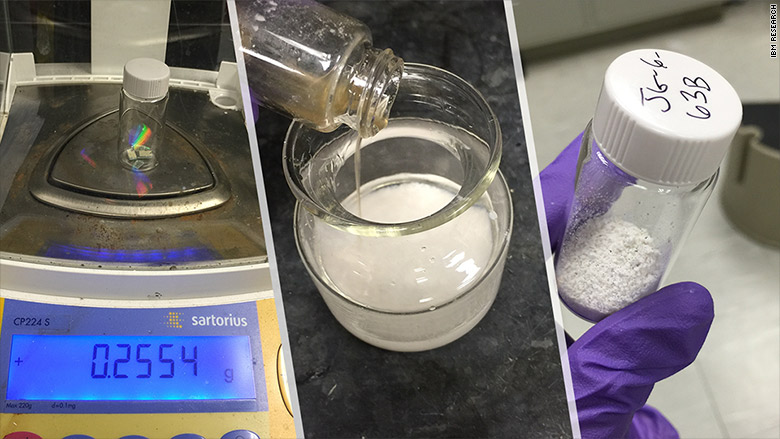

She described the process using an old CD. Garcia and Jones cut old CDs into small pieces, added a reactant that would seal in the BPA, and a powder very similar to baking soda. They heated the mixture at 190˚C.

They found that the new plastic could not only withstand high temperatures but also resisted the decomposition process that causes BPA to leach.

Moreover, Garcia said the recycling process could eventually keep more used plastic products out of landfills. "It's an environmental win on many fronts," she said.

The repurposed plastic, she said, could be safe enough to use in water purification systems, fiber optics and even medical equipment.

Related: These clothes can wirelessly charge your phone

Garcia and Jones are now looking for commercial partners to take their innovation to the next level.

"This is a brand new process, so we are a few years away from widespread adoption," she said. "But we do want to eventually scale this up."