On the first day of the Democratic National Convention last month, Demetrios Marantis walked into a reception wearing jeans, an open-collared shirt, a little too much stubble and a suntan.

Then he took his place on a panel alongside a member of Congress.

"Some of my former colleagues were looking at me like, 'What happened to you? Where is your tie?' " Marantis says. One colleague later told him he looked like a "California hipster."

What happened to Marantis was Silicon Valley.

Marantis served as the Acting U.S. Trade Representative and a member of President Obama's cabinet, responsible for negotiating and enforcing international deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. But in 2013, Marantis left D.C. for sunny California and an executive role at Square (SQ), a payments company.

"I didn't know what to expect," says Marantis, who wanted to try helping small businesses through technology rather than trade policies. "It was the beginning of the exodus of people from D.C. moving to the Bay Area."

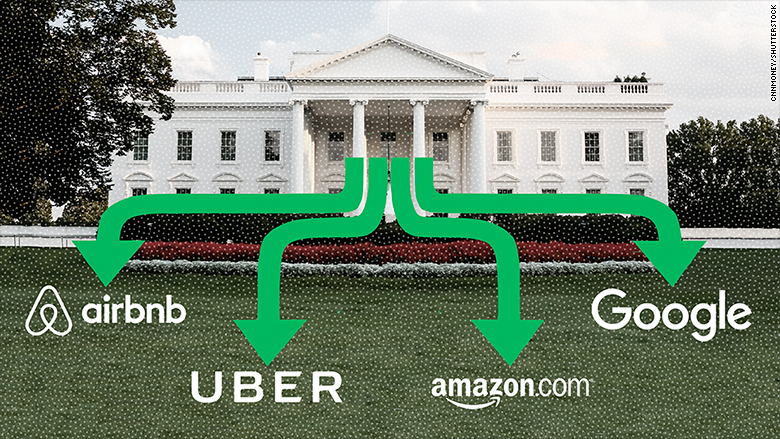

Marantis was one of the first Obama staffers to head west to be part of the tech scene. Since then, dozens of officials from all parts of the Obama administration have followed in his footsteps, including prominent figures like campaign manager David Plouffe (Uber), Environmental Protection Agency head Lisa Jackson (Apple (AAPL)) and most recently Attorney General Eric Holder (Airbnb).

Related: Google vs. the cable guys: the big fight over the little set-top box in your home

There was a steady drip of employees bouncing between government and tech before Obama took office. Sheryl Sandberg, for example, worked as chief of staff to Treasury Secretary Larry Summers in the '90s before taking executive roles at Google (GOOGL) and Facebook (FB).

But so many members of Obama's administration have gone to San Francisco that one former political official now in the tech industry likened it to American expats hanging out in Paris after World War I.

The Obama alumni now form an influential network in Silicon Valley that stands out from the pack.

Ryan Metcalf, a former senior analyst in Obama's White House who now works as chief of staff for PayPal cofounder Max Levchin, recalls showing up to his first meeting with Levchin wearing a flag lapel pin. "[Levchin] was like, 'Who are you? What are you doing in my office? I don't know if you're trying to be my security.' "

Metcalf and his peers from the administration had to learn to dress more like techies, trade D.C. jargon for tech speak like "disruption" and push for conversations about regulation and policy in an industry that cares more about building things fast.

"We're viewed as foreigners," Metcalf says. "In startup culture, it's like these regulations and all this stuff is just a burden."

Yet, this group of foreigners is only growing larger. Tech companies are turning to people with political experience as they encounter more scrutiny over public safety, discrimination, privacy and regulatory issues from pushing into markets like ride-hailing, home rentals and banking.

"It wasn't a goal of mine," says Nick Shapiro, former deputy chief of staff at the CIA who joined Airbnb in December to head crisis communications. "But time and time again you get hit up by companies in San Francisco who see what you've done in government and where you've been. They're looking for people who understand the intersection of press, politics and policy."

When he was ready to leave government, Shapiro looked at where other officials in similar roles had gone. Those in the Clinton administration, he found, went to New York. Those in the Bush administration went back to Texas. And he noticed those in Obama's administration went to San Francisco.

"I'm surrounded by many of the same people I was surrounded by in the White House itself," Shapiro says. "There's a feeling of familiarity knowing you have a strong support network. Probably if I needed something at another company, one of my first calls would be to another Obama alumni."

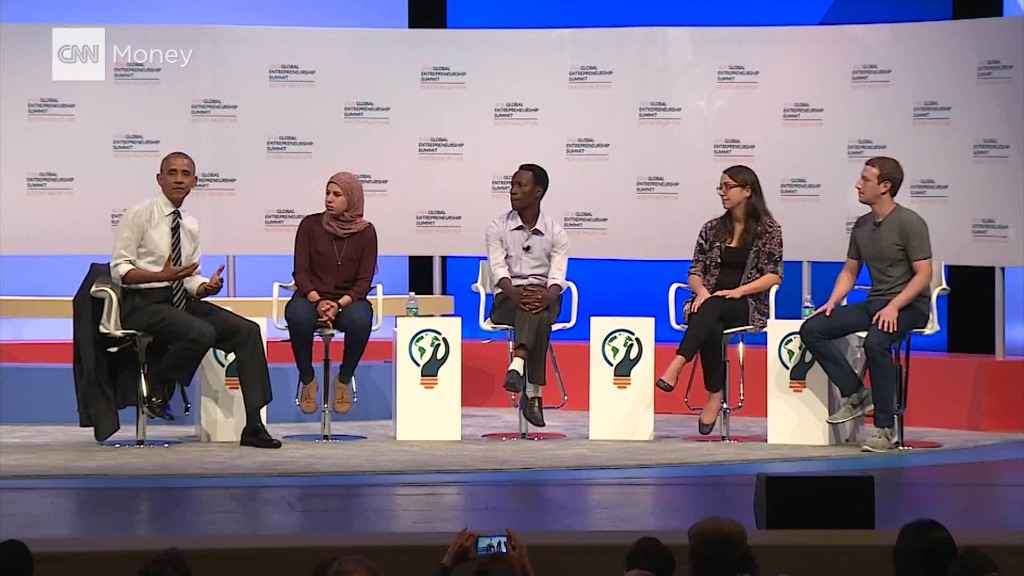

Even Obama himself has hinted at a desire to dabble as a venture capitalist after his presidency ends.

For some, Silicon Valley offers the promise of making an impact on the world through a fast-moving tech company rather than a sluggish government bureaucracy.

"There is an undeniable appeal to the growth and excitement of the tech industry -- especially when contrasted to working in a large bureaucracy with a lot of rules and a lot of reasons to say no," says Nick Sinai, former U.S. Deputy Chief Technology Officer and now a venture capitalist with Insight Venture Partners.

Many are searching for some combination of better pay, something resembling a work/life balance, fewer partisan battles and a more dynamic city after years of sacrificing these for the sake of a meaningful government job.

"We went to D.C. and did our time. That was our public service," Metcalf says. "Some people come here to cash out. You're probably nearing your 30s, have zero in retirement. Some people want to start families. You're never going to own a home here, but at least you'll be well compensated."

The allure of Silicon Valley is particularly strong among the many young staffers who worked for the Obama administration or his presidential campaigns, the latter of which have often been compared to a startup.

"The younger folks at the White House thought it was really cool," Nick Papas, director of public affairs PR at Airbnb, says of the reaction from colleagues when he left to join the travel startup. "Some of the folks who were a little older thought I was going to start a bed and breakfast."

Whatever their reasons for leaving D.C., all those we spoke with expressed relief to be gone as the general election gets underway. But they continue to follow it closely from afar.

"You can take the boy out of DC," says Marantis, who now works down the block from Square at Visa (V), "but you can't take the D.C. out of the boy."