Fans waited four years for Frank Ocean to put out a followup to his Grammy-winning album Channel Orange, but when he finally released it this month, some listeners were upset to learn it was only streaming on Apple Music.

"You're tellin me I switched to Tidal & Frank gotta go and drop an album exclusively for Apple Music?" one person tweeted. "I do not have time for you Frank Ocean."

Ocean's release was just the latest example of tech companies vying for exclusives on new albums in a bid to attract customers. It's a tactic that has become more common over the last 18 months as streaming services try to differentiate themselves in an increasingly competitive and combative market.

Apple Music, built on top of the company's $3 billion purchase of Beats, and Tidal, the service owned by Jay Z, have been the most aggressive in signing up exclusives. These include Ocean, Drake and Taylor Swift for Apple and Prince, Beyonce and Kanye West for Tidal.

The exclusives can go on indefinitely, in the case of Prince, or last as little as 24 hours. The rewards can be significant: Tidal got more than one million customers to create accounts in the first week that Beyonce's album Lemonade was released, according to the New York Times.

The two companies have clashed with each other in the process. After a rumor that Apple (AAPL) would buy Tidal, West tweeted that "this Tidal Apple beef is f***ng up the music game."

Apple and Tidal may have also angered Spotify, which was recently reported to have penalized artists for signing exclusive deals with rivals by making their music harder to find. (Spotify later denied it.)

More disputes may be coming. Amazon (AMZN), which has a track record of bidding to stream exclusive videos, is said to be planning to launch a streaming music option as soon as next month.

Pandora (P) is rumored to be working on an on-demand streaming service too, moving beyond online radio.

Related: 'Carpool Karaoke' series will be exclusively on Apple Music

For a few years, the streaming market was dominated by Spotify and smaller services of varying legality, with less headbutting over exclusive deals.

"That was a really good period. You didn't have to worry about who you were offending," says Ted Cohen, managing partner at Tag Strategic and a former music exec who worked at EMI. "Now it's getting territorial again."

Suddenly big tech companies all want a piece of the pie.

"A major reason why you buy iPhones, Android phones and Amazon Echos is because you play music on them," says David Pakman, a venture capitalist at Venrock and former CEO of eMusic. "Right now, the current tactic [tech companies] are using to fight with each other is not features, it's content."

The price is the same for most -- around $9.99. So a key difference is the selection. As a result, Pakman says the push for exclusive music deals is becoming "the strategy of the moment."

To get those deals, music streaming services have brought on prominent figures from the recording industry who have clout with leading musicians.

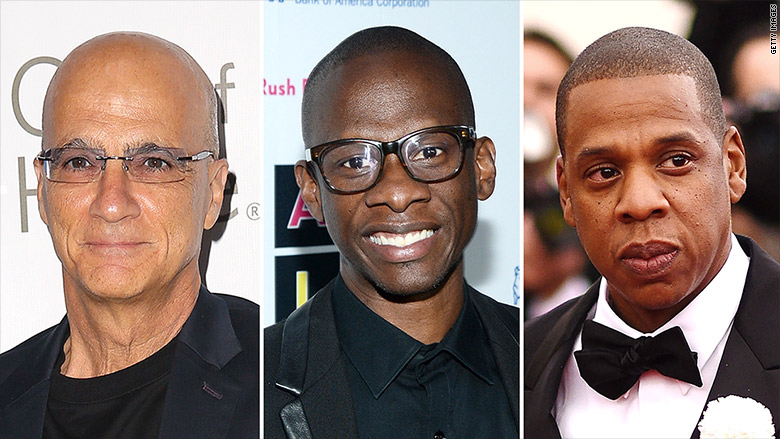

Chief among them is Jimmy Iovine, the former head of Interscope Records and cofounder of Beats, who now runs Apple Music. Under the leadership of Iovine and head of original music content Larry Jackson, Apple has worked to broaden the idea of music exclusives.

"Larry and Jimmy don't just think of content as the album or the recording," says Neil Smith, former head of business development at Beats Music who now works with MediaNet. "The exclusive isn't just the album or the single. It's that and the stuff around it."

In the case of Frank Ocean, that meant Apple getting exclusives to a new audio album as well as a separate "visual album" and hosting a live stream from Ocean before the release.

Related: Will buying Tidal help Apple fend off Spotify?

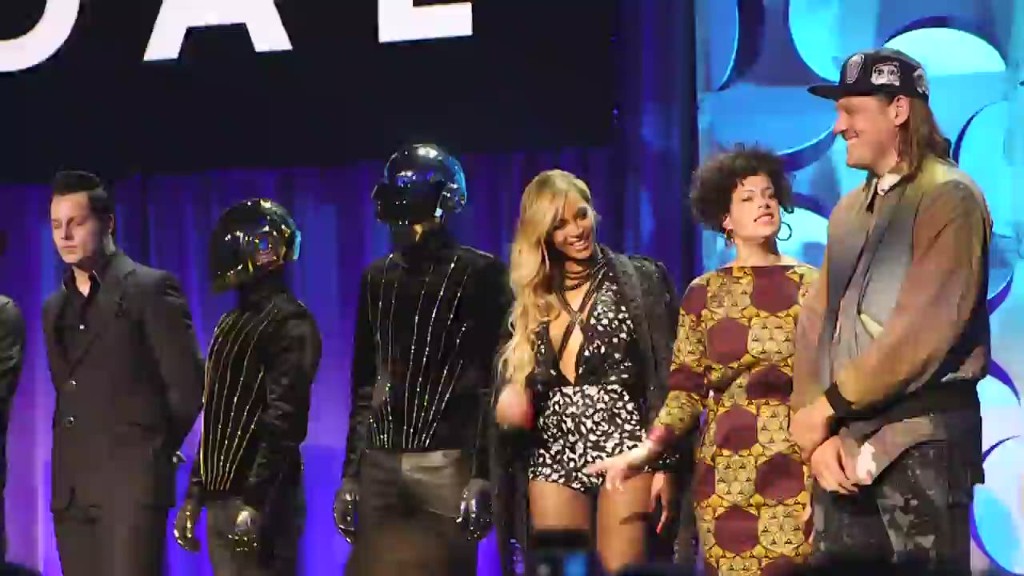

Tidal, meanwhile, has capitalized on its impressive list of owners, including Jay Z, Kanye West, Chris Martin and Rihanna, to land coveted exclusives.

Even Spotify, which has not publicly gone after exclusive deals, has nonetheless brought on Troy Carter, who has managed artists like Lady Gaga.

As Jay Samit, a former exec at Sony (SNE), put it, this is what companies feel is necessary "when a handful of current acts make up 40%-50% of all music revenue and there's a handful of executives who have access to them."

But this approach comes at a cost -- more money spent courting artists, more frustration for listeners who just want everything in one place and more crossfire all around in the industry.

"Everybody is being as aggressive in the current marketplace as terrestrial radio was," says Cohen, referring to the days of record execs jockeying for airplay. "It's just a different set of weapons."