The money printing presses are spinning fast.

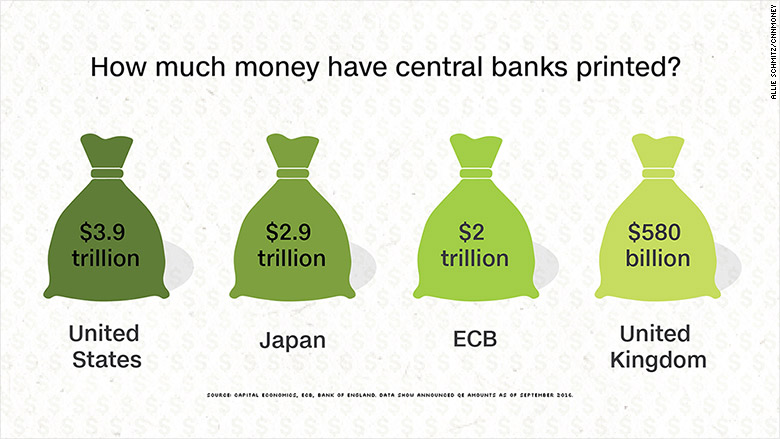

The world's four most powerful central banks have pumped more than $9 trillion into the global economy since the financial crisis in a bid to boost growth, inflation and employment.

That's a huge number, equivalent to the value of all the goods and services the U.S. produces in six months.

"If you brought a group of economists from 2008 to the present day and told them that central banks had bought $9 trillion in assets and were still looking for ways to boost inflation, I don't think they would believe you," said Michael Pearce, global economist at Capital Economics.

Central banks started creating new money in vast quantities as the world went into recession. The plan was simple: Injecting more money into the system would encourage commercial banks to lend, which would in turn lead to more business and household spending.

In normal times, it is enough for central banks to cut interest rates to prompt lending. But record low interest rates, and in some cases, negative interest rates weren't doing enough. So they turned to stronger medicine and experimented with buying bonds to flood markets with new money. Experts are divided over whether it works.

"The main effects appear to have been to lower longer-term interest rates and to boost equity prices," Pearce said. "There is little evidence that this has increased economic growth or inflation significantly," he added.

Related: Helicopter money: central banks' last resort

The Federal Reserve alone has injected $3.9 trillion dollars via three rounds of asset buying. It started in November 2008, shortly after the financial world went into meltdown, and continued until October 2014.

The Bank of England followed in March 2009, adding 375 billion pounds ($500 billion) in three rounds of stimulus. It revived its program in August this year after the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, dealing a blow to growth.

The Bank of Japan -- which had dabbled with a bond buying program between 2001 and 2006 to fight deflation -- entered the fray in April 2013, buying $2.5 trillion in assets since then, according to data from Capital Economics.

The European Central Bank came late to the party, launching its own stimulus program in March 2015. It plans to buy 1.7 trillion euros ($2 trillion) worth of assets by March 2017. It reiterated Thursday that it would pump out even more money beyond that date if necessary.

-- Anastasia Anashkina contributed reporting.