When does satire become defamation?

Charlie Hebdo may be about to find out after officials of an Italian town said they wanted prosecutors to take action against the French magazine for depicting earthquake victims as pasta dishes, and appearing to blame the mafia for the death toll.

An earthquake last month killed at least 290 people, most of whom lived in Amatrice -- home to the famous amatriciana pasta sauce.

Amatrice town council filed a petition for "aggravated defamation" with a local prosecutor on Monday, its lawyer Mario Cicchetti told CNN. The prosecutor will consider the claim before deciding whether to pursue the magazine.

The complaint centers on two cartoons Charlie Hebdo published after the quake.

The first, headlined "Earthquake, Italian-style," showed victims with varying degrees of injury, each likened to an Italian recipe.

It sparked outrage in Italy, and prompted the French embassy in Rome to issue a statement distancing itself from the publication.

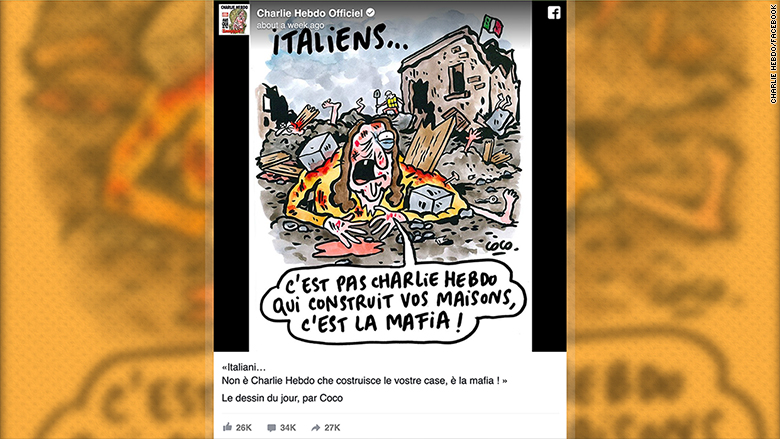

The second stated: "Italians... it's not Charlie Hebdo that builds your homes, it's the mafia!"

Amatrice was left in ruins. Many of the houses in the area -- unreinforced brick or concrete frame buildings -- were vulnerable to earthquakes, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and offered little resistance to the powerful quake.

The town council said the cartoon "attributed the blame for the devastation of central Italy to the mafia."

"Criticism, even in the form of satire, is an inviolable right both in Italy and France, but not everything can be 'satire' and in this case the two cartoons offend the memory of all the victims of the earthquake, the people who survived and the town of Amatrice," Cicchetti was quoted as saying by Italian news agency ANSA.

Charlie Hebdo declined to comment on the likely legal action.

"Charlie Hebdo's newroom has no comments to make. For now, they are not intending to respond to this situation," said a spokesperson for the magazine.

Related: Charlie Hebdo cartoonist done with drawing Mohammed

The publication became an international symbol of free expression after an attack on its newsroom in January 2015 left 12 people dead, including its top editor and several of the publication's cartoonists.

The shooting was in retaliation for the newspaper's caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed, a serious affront to some Muslims.

A little more than a week after that attack, Charlie Hebdo put out another issue that featured a cartoon depiction of Mohammed on the cover.

-- Nicola Ruotolo in Rome and Camille Verdier in Paris contributed to this article.