An Ethiopian chemist washing dishes in a high school cafeteria. An Egyptian electrical engineer busing tables at a Burger King. A computer scientist from Cameroon packaging food for prisons.

Millions of highly educated immigrants come to the U.S. seeking a better life, only to end up either working hourly, low-skilled jobs, underemployed or out of work.

According to a new report from the Migration Policy Institute, nearly 1.5 million college educated immigrants were employed in low-skilled positions between 2009 and 2013. If this group had worked in middle or highly skilled jobs, researchers found that they would have earned nearly $39.4 billion more a year. That would translate into nearly $10.2 billion more in federal, state and local taxes, the institute reported.

"More attention should be paid to ensuring that all workers, regardless of their origin, are given the opportunity to fully utilize their human capital," the nonprofit research firm said in its report.

Immigration among the college educated has risen sharply in recent years. Between 2011 and 2015, almost half (48%) of arrivals were college graduates compared to 33% before the recession, MPI found.

Related: Immigrants, these cities want you!

Yet, language barriers, visa issues and cultural hurdles block many of these immigrants from attaining jobs that meet their skill sets. Another major issue is that foreign degrees and work experience often don't hold as much weight as a U.S.-based degree or job.

Some cities like St. Louis, Cincinnati, Detroit and Pittsburgh are trying to change that. They recognize how their economies could benefit from an immigrant professionals and entrepreneurs and have begun efforts to attract them. St. Louis' Mosaic Project, for example, is a public/private partnership that matches immigrants with local professionals and business owners to improve employment opportunities for these newcomers.

And states like Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York and Pennsylvania are working on policies that will more seamlessly recognize professional credentials from other countries, MPI said.

The computer scientist from Cameroon

Originally from Cameroon, Anicet Wafo Kom landed in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 2015 after winning a green card lottery.

The 31-year-old came with a bachelor's degree in computer science and a desire to grow professionally, but Kom struggled with English.

"My first interviews were tough," he said, noting that he lacked confidence when he spoke English.

To get by, he took a job packaging prison food at a nearby factory making minimum wage. He worked there for seven months while he sought another job. "It allowed me to buy a car and pay my bills," he said.

In 2016, his uncle introduced him to Upwardly Global, a nonprofit based in New York that has helped hundreds of highly skilled immigrants find work in their field. The group helped Kom fine tune his resume and hone his speaking and interviewing skills.

Related: How immigrants can revive America's blighted neighborhoods

In May, after about seven months of working with Upwardly Global, he found a job as a business intelligence analyst at Two Men and a Truck, a moving company based in Lansing, Michigan.

"I'm very happy to wake up in the morning to go to the office," he said.

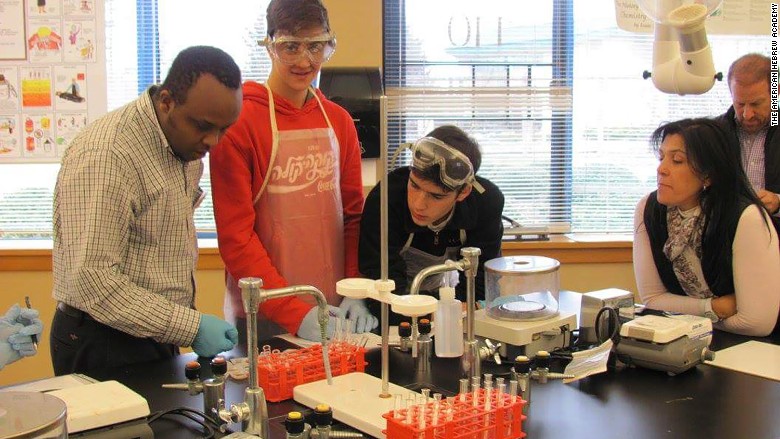

The Ethiopian chemistry teacher

Samuel Tesfay, 34, immigrated from Ethiopia to Greensboro, North Carolina, in 2013 with a master's in analytical chemistry from Addis Ababa University.

"My plan was to go to school and pursue my PhD," Tesfay said.

He hoped to eventually help his wife, who was four months pregnant at the time, immigrate to the U.S. But finding work in his field proved difficult.

"I decided to look for any kind of job, as long as it was in an educational environment. I thought I'd have a chance to network with other professionals," Tesfay said.

Related: How this Vietnamese refugee became Uber's CTO

A friend found him work as a dishwasher at The American Hebrew Academy, a Jewish boarding school in Greensboro.

A few months into the job, Tesfay emailed the dean to inquire about a teaching position. There weren't any openings, but she recommended he start tutoring, he said.

He began with math and soon the math teacher was recommending him to other teachers. "I started tutoring in physics and chemistry," he said.

After tutoring for about a year, a job opened at the school and he was hired.

Now Tesfay is in his second year as a full-time chemistry teacher. He also recently celebrated his first American Thanksgiving with his wife and daughter, who immigrated to the U.S. this year with the help of the school's legal staff.

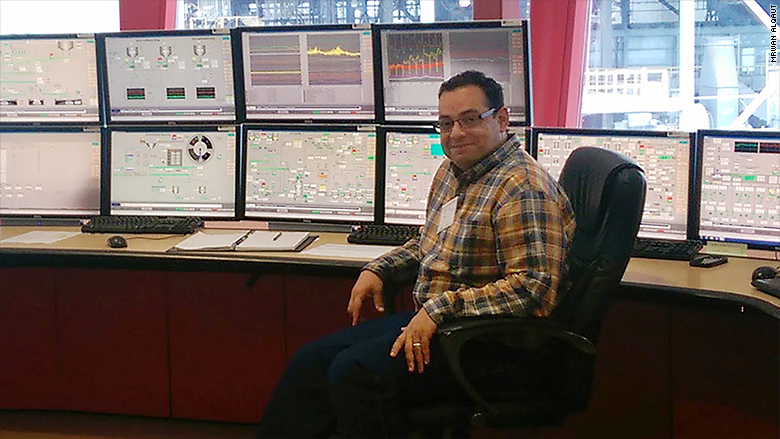

An electrical engineer from Egypt

Mrwan Alqaut, 57, immigrated from Egypt in 2012, after he too won a green card lottery.

"It was the first time I was lucky in my life," he said.

With $10,000 and nine years' experience as an electrical engineer he expected to find better work in the U.S.

But in two weeks, he'd spent $5,000, he said. "I went to California, everywhere, looking for work and then I came to New York City," Alqaut said. "I thought I could be better in New York because there was more diversity and more people from my country."

Related: Nigerian immigrant dreams of finding cures for infectious diseases

"After four months, I had $800 and I had to make a decision: Pay the rent or go back to my country."

He stayed and got a job as a busboy at a Burger King, where he worked for a year.

One day he stumbled across Upwardly Global online. There he optimized his "Egyptian-style" resume which was just focused on his technical background and had no cover letter.

He also practiced his interview skills. "They gave me the resources I needed." he said. "They told us how much we had to make and how to sell our knowledge and experience."

Today, he lives in Maryland and works as an electrical engineer with Holcim, a large global cement producer.

Before finding this job, Alqaut says he was extremely depressed.

"It's like you can see something very beautiful, but you can't have it because there's a big glass wall and you can't cross it."