The Reserve Bank of India acknowledged Wednesday that the country's ongoing cash crunch is hurting the economy.

The central bank slashed its growth forecast for the current financial year by half a percentage point, citing "uncertainty" resulting from Prime Minister Narendra Modi's shock decision to ban 500 and 1,000 rupee notes.

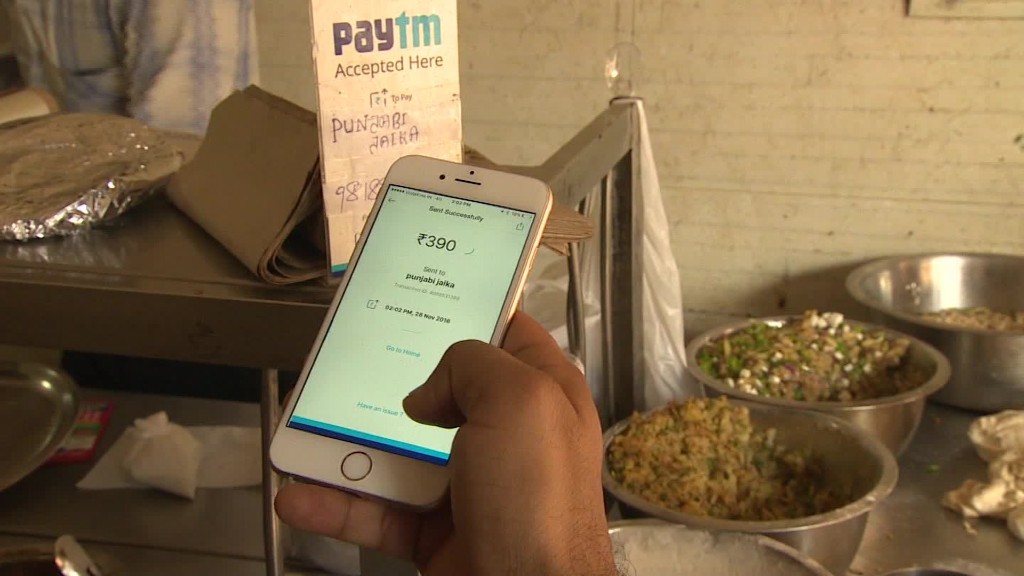

The ban, which was announced on Nov. 8, abruptly took 86% of legal notes out of circulation and led to an acute cash shortage.

More than 90% of daily transactions in India are made using cash, and analysts predict the disruption could knock as much as one percentage point off India's 7.3% growth rate over the next two quarters.

The central bank also sees evidence of slower growth as millions of Indians continue to line up to deposit canceled notes.

"Supply disruptions in the backwash of currency replacement may drag down growth this year," the central bank said in a statement. "The [economic] assessment is clouded by the still unfolding effects."

The RBI said it expects damage from the cash crisis to be temporary, but downgraded one of its key economic indicators. The bank now expects growth of 7.1% for the current financial year, down from its previous estimate of 7.6%.

More than 80% of the 14 trillion rupees ($209 billion) in banned notes have been returned, the RBI said. But the central bank has supplied only 4 trillion rupees ($56 billion) in replacement currency over the past month, leaving a huge cash vacuum.

Related: India's boom continues but for how much longer?

Despite the shortage, the RBI chose to keep the rate at which it lends to banks at 6.25%. That decision surprised economists, many of whom had expected the bank to cut rates in an effort to counter the monetary crunch.

"If economic activity has been damaged as much as many fear, the RBI's wait-and-see approach will come to be seen as complacent," wrote analysts at Capital Economics.

Related: India just made it even harder to get hold of new cash

The central bank, which is responsible for printing replacement rupee notes, also defended its role in the cash crisis.

"The decision [to ban the notes] has not been taken in haste, but after detailed deliberations," said Urjit Patel, who became RBI chief in September. "High secrecy had to be maintained."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the potential negative impact to gross domestic product growth from the rupee ban.