Can a career oil man help save the planet?

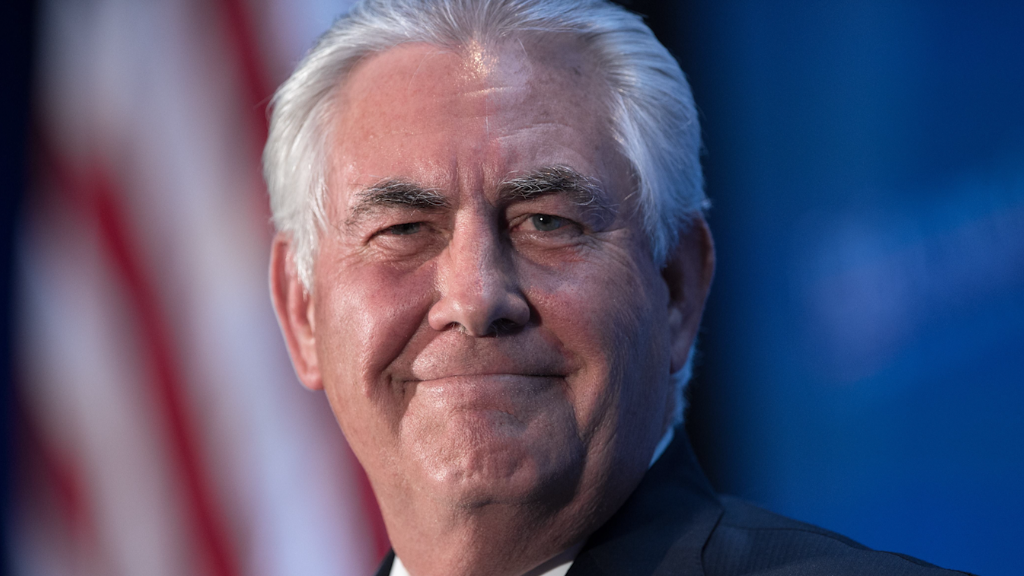

That's one key question as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to nominate ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson as secretary of state.

As secretary of state, Tillerson would be the country's key emissary on climate issues. He could negotiate a U.S. exit from the Paris climate accords, which John Kerry signed, and approve the Keystone XL pipeline.

Exxon, the world's leading oil company, has a complex relationship with global warming. It's under investigation for allegedly misleading investors and the public about the effects of climate change. The corporation denies it's done anything wrong, but acknowledges climate change is a real problem.

Tillerson's record is similarly complex. He's spent his working life at Exxon, which for years denied that burning fossil fuels contributes to climate change. But the company has softened its stance since he took the helm in 2006.

Exxon (XOM) even expressed support for the Paris agreement, which Trump opposed during the campaign. Exxon described the deal as "an important step forward by world governments in addressing the serious risks of climate change" in November.

And Tillerson, in a speech at the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition, said "both developed and developing countries are now working together to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions" because of the agreement.

That kind of language could put Tillerson at odds with Trump, who on Sunday said on "Fox News Sunday" that "nobody really knows" if climate change is real.

Tillerson's stance on climate change also marks a major change from what Exxon said in the past.

When Tillerson took charge, Exxon was struggling to balance its corporate interests with a growing public consensus on global warming, according to Steven Coll's book "Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power."

Under former CEO Lee Raymond, ExxonMobil promoted skepticism about the science of climate change. Raymond railed against the Kyoto Protocol, an earlier global climate pact, in a 1997 speech in China, saying the need for costly regulations and restrictions had "yet to be proven." He also claimed the greenhouse effect mostly came from natural sources.

Raymond later dialed down his position and admitted that global warming needed to be addressed, but he remained a staunch opponent of any formal regulations.

When Tillerson -- a longtime Raymond deputy -- became CEO, ExxonMobil saw an opening to begin adjusting its position on climate change, according to Coll.

In 2007, the company publicly admitted climate change presents risks, and said it is responsible policy to begin working to reduce emissions.

"While there are a range of possible outcomes, the risk posed by rising greenhouse gas emissions could prove to be significant," Tillerson said in a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations in 2007. "So it has been ExxonMobil's view for some time that it is prudent to take action while accommodating the uncertainties that remain."

The company often emphasizes technical solutions that won't hurt energy output or disproportionately raise consumer costs. Tillerson touted, in his speech in Abu Dhabi last month, an Exxon partnership that's researching how fuel cells can be used to capture emissions from power plants.

Today, climate change is also causing legal headaches for Exxon. New York's attorney general announced in November 2015 that his office is investigating whether the company withheld information from shareholders and the public about the risks of climate change. Massachusetts launched a similar investigation in April 2016.

Related: ExxonMobil facing climate change probe

Exxon could face massive legal costs if officials are able to prove it funded research that downplayed the risk of climate change while its own research documented negative effects. That's what happened in the 1990s and 2000s to the tobacco industry.

ExxonMobil, which did not respond to requests for comment for this story, denies those claims.

"We unequivocally reject allegations that ExxonMobil suppressed climate change research contained in media reports that are inaccurate distortions of ExxonMobil's nearly 40-year history of climate research," it says on its website.