The latest round in the epic health care reform battle has begun.

After decades of circling each other, the Democrats gained the upper hand in 2010, making their philosophy of universal health care coverage the law of the land. They called it the Affordable Care Act.

Now the advantage lies with the Republicans, who suddenly have the opportunity to advance their brand of universal health care access. The names of the repeal legislation floated over the years provides insights into their priorities. The Empowering Patients First Act. The Healthcare Accessibility, Empowerment, and Liberty Act. The Patient CARE Act.

While the Republicans have yet to issue a detailed plan to replace Obamacare, many of their proposals share common traits. CNNMoney lays them out for you as a guide to the Congressional battle that lies ahead.

Universal coverage vs. universal access:

A primary goal of Obamacare was to make sure all Americans -- or nearly all -- obtained health insurance. It created insurance exchanges for those seeking individual coverage and expanded Medicaid for low-income adults. It offered a mix of incentives and penalties to entice people to sign up.

Republicans have a different take. Rather than emphasizing coverage, they back making health insurance more accessible. They promise to lower the cost of premiums to make coverage more affordable so that more people can buy policies.

Comprehensive benefits vs bare bones coverage:

Obamacare requires that insurers cover lots of benefits that were hard to find in the individual market beforehand. Think: maternity care, mental health and prescription drugs. Under Obamacare, Americans can get preventative services, such as annual check-ups, cholesterol screening and certain vaccines, for free.

The law also provides other protections for Americans. It caps how much consumers paid out of pocket each year and ended insurers' practice of placing a dollar limit on how much they paid annually or over one's lifetime.

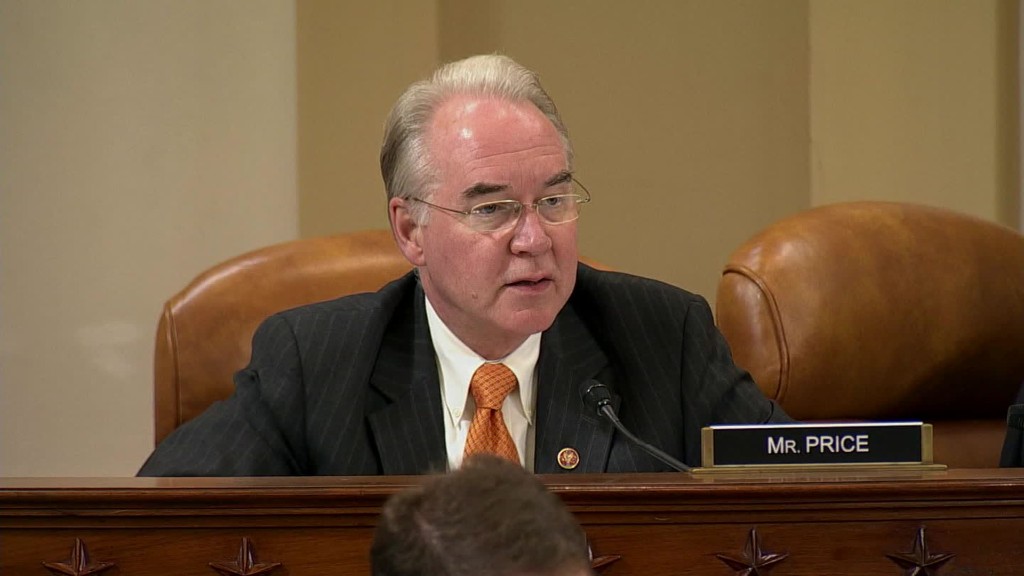

Related: How Trump's health secretary pick would replace Obamacare

Republicans argue mandating such comprehensive benefits drive up cost. They want to give consumers more choice. They say Americans should be able to pick the benefits they want -- why should a 55-year-old couple pay for maternity benefits?

This increased flexibility will likely mean lower premiums, though it could also mean higher deductibles. But that's okay with Republicans, who tout the concept of consumer-directed health care. The more people have to pay out of pocket, the wiser spending choices they'll make, the thinking goes. If people have to shell out $75 for a blood test, they'll think twice about whether they really need it or they will shop around to see if they can get it cheaper elsewhere.

Premium subsidies vs. tax credits:

Under Obamacare, the federal government provides a helping hand for low- and moderate-income enrollees in the form of premium subsidies, which are officially tax credits offered in advance. The less you earn, the higher the subsidy. More than eight in 10 Obamacare enrollees get premium subsidies, which lower their cost to less than 10% of their income.

The Republican replacement plans also provide tax credits to cover premiums. But the size of the Republican credits would be based on age, not income. Younger enrollees would get less than those age 50 and over.

Also, to help pay for coverage, Republicans would encourage the use of a favored tool: health savings accounts. HSAs allow people to sock away funds tax free for medical expenses. But it's mainly used by higher-income Americans, who can afford to contribute to them.

Pre-existing conditions ban vs. continuous coverage:

Obamacare barred insurers from discriminating against those with pre-existing conditions. Insurers could not reject those who had been sick, nor charge them more.

Republicans say they would protect people with pre-existing conditions -- if they've maintained continuous insurance coverage. That means if you have a gap in coverage — say, because you left your job and couldn't afford coverage on the individual market — you might not be protected.

Those who are uninsured and sick may be charged more or may have to look for coverage through state high-risk pools, which had a very troubled history before they were essentially disbanded after Obamacare's individual exchanges opened in 2014.

Related: How Trump may cover Americans with pre-existing conditions

Taxing high-cost employer plans vs. capping tax deduction:

Many lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle want to rein in the cost of employer-sponsored insurance plans, which cover 150 million Americans. These plans often offer rich benefits packages, which employees like to utilize, driving up the nation's health care spending.

Obamacare called for instituting the so-called Cadillac Tax. It would impose a 40% levy on the amount of employer premiums above $10,200 for individual and $27,500 for family policies. The idea is to have employers limit their benefits packages to a certain level, slowing the growth of health care spending and usage.

But even though the Cadillac Tax is in President Obama's landmark health reform law, it is not universally endorsed by Democrats. In fact, Congress came together to push back the date the tax is to go into effect to 2020, from 2018.

Republicans, on the other hand, would limit costs in employer plans by capping the tax deduction for premiums. The rationale is that this will force employers to provide less generous policies so their workers don't get socked with a tax bill.

Related: Repealing Obamacare affects everyone

Medicaid expansion vs fixed grants:

In keeping with its universal coverage philosophy, Obamacare aimed to expand Medicaid to all adults with incomes below 138% of the poverty level. Prior to Obamacare, most enrollees were low-income children, pregnant women, parents, the disabled and the elderly. The federal government enticed states by covering 100% of the cost of the newly eligible for three years and lowered reimbursement to 90% over time.

Related: Major changes for Medicaid coming under Trump and the GOP

Republicans have long favored turning Medicaid into a grant program. They would either provide states with a set amount of funds, known as a block grant, or provide a certain amount of money to cover each enrollee, which is called a per-capita grant. This would help curtail the growth of Medicaid spending and make it a more predictable cost for the federal government. But consumer advocates worry that funding caps will restrict the number of people who can enroll and the quality of care they receive.