For all the headaches on Capitol Hill over Obamacare, tax reform, 2018 budget proposals and the Russia investigations, there is one issue that lawmakers simply can't afford to ignore much longer: Congress must raise or suspend the debt ceiling this year.

But the $20 trillion question is when, exactly, that must happen -- and just as importantly, when it will happen. While no one knows for sure on either count, something needs to happen soon if the United States is to avoid defaulting on any of its bills.

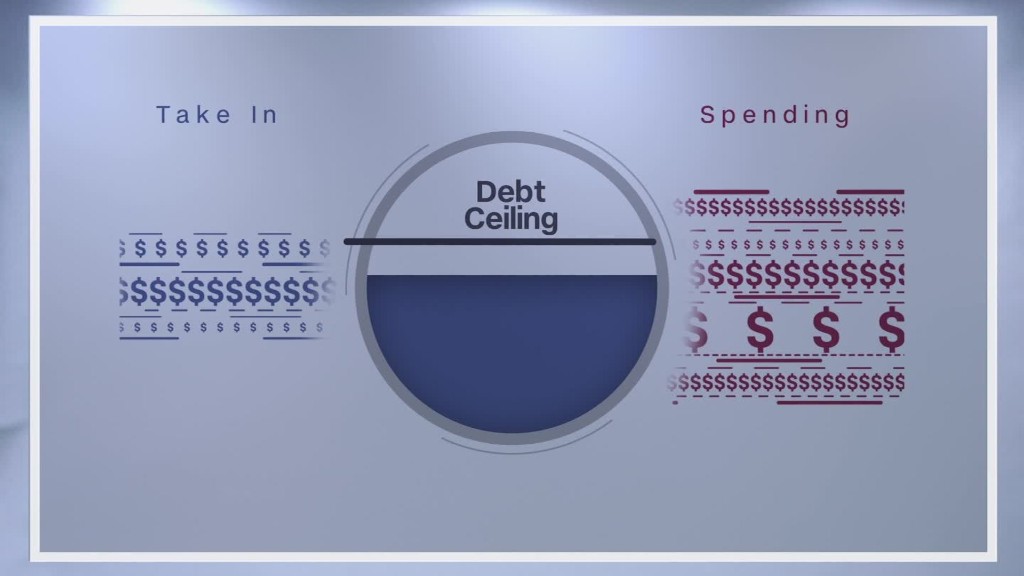

The legal cap on U.S. borrowing is currently set at $19.81 trillion. Since mid-March, when the last debt ceiling suspension ended, the Treasury Department has been using special accounting measures to keep debt below that limit in order to continue paying all the country's bills in full and on time.

But those measures will only last so long. When they run out, Treasury will only be able to pay bills with the cash and revenue it has on hand. And there won't be enough to cover everything on a daily basis.

Related: Mnuchin calls out debt limit as a 'ridiculous concept'

Both the Congressional Budget Office and the Bipartisan Policy Center have estimated the so-called extraordinary measures will likely be exhausted sometime this fall. But Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin hasn't offered an official estimate.

What he did do last week, however, is suggest to lawmakers that they act before they leave for their August recess. That, combined with a comment from White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney that revenue appears to be coming in "a little bit slower than expected," has had people worried that the must-act-deadline for Congress will come even earlier than the fall.

But in fact Mnuchin has been on record urging lawmakers to deal with the debt ceiling since his confirmation hearings this past winter. In March, for instance, he also suggested they act before the August recess.

Here's why: Projections of when extraordinary measures will run out are always uncertain because revenue flows are hard to predict with precision.

So if Congress relies on them to postpone action until the very last moment and the projections turn out to be wrong, the United States could default on some of its legal obligations.

Those obligations include paying bondholders, federal contractors, Social Security recipients, tax filers owed refunds and a vast array of other parties. Missing payments to any of them could hurt the economy and markets to varying degrees, depending on who gets stiffed and for how long.

Related: Mnuchin to Congress: Raise the debt ceiling before you go home

To guarantee the government won't miss a payment, lawmakers should raise or suspend the ceiling before going on their August recess, said Shai Akabas, the Bipartisan Policy Center's director of fiscal policy. "If they come back mid-September and haven't yet addressed it, things start getting dicey."

Unfortunately, cutting a debt ceiling deal will also be dicey, said Greg Valliere, chief global strategist of Horizon Investments, in a morning note.

By that he means the conservative Freedom Caucus in the House will likely demand more spending cuts and budget reforms in exchange for their vote. So House Speaker Paul Ryan may have to bring House Democrats on board to pass an increase or suspension. And those Democrats will have their own demands.

"You can bet on two things," Valliere said. "[House Minority Leader Nancy] Pelosi will seek major spending concessions, and the GOP base will howl."