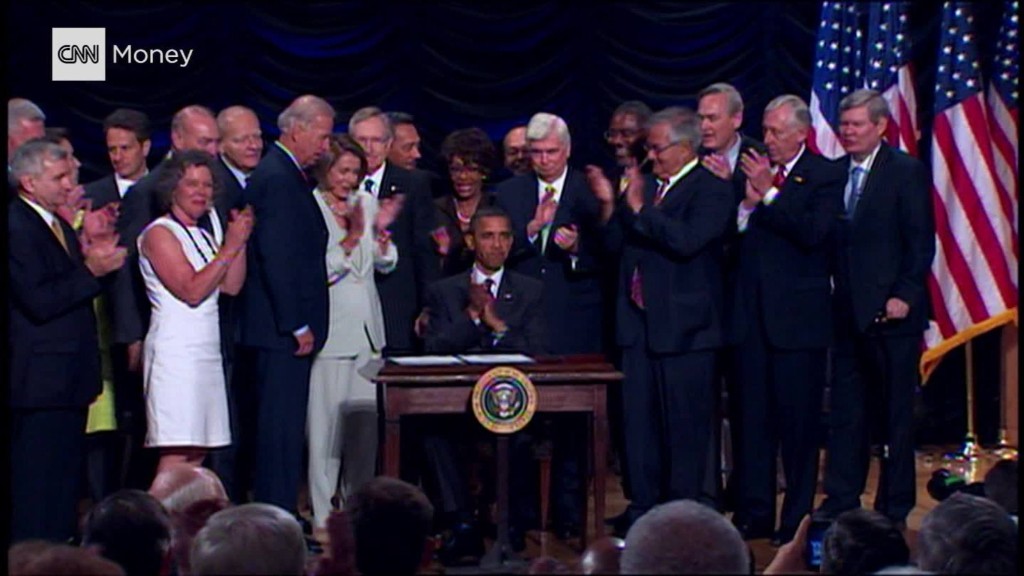

President Trump promised to do a "big number" on the 2010 Dodd-Frank law that Congress and President Obama enacted after the financial crisis.

"Dodd-Frank is a disaster," Trump said when he signed an executive order calling for less regulation after taking office.

Now he's following through.

In a 150-page report released Monday by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, the administration calls for dismantling strict regulations overseeing Wall Street banks.

The report would hand the president the power to fire the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency established in 2010 that has proven controversial on Wall Street but has been heralded by consumer advocates.

Fifteen pages of recommendations resemble significant aspects of the Republican bill passed last week by the House.

Trump had given Mnuchin 120 days to come up with a plan to address what he said were onerous regulations crimping banks' ability to lend and stifling economic growth.

"Treasury proposal advances ideas that have been pushed by industry lobbyists since Dodd-Frank was passed," said Lisa Donner, executive director for Americans for Financial Reform, a group that has fought to protect Obama-era rules.

Related: The most dangerous part about killing Dodd-Frank

During his campaign last year, Trump often slammed Wall Street for "getting away with murder."

But now he is embracing it. He has backed away from promises to break up the biggest banks. He's also stacked his cabinet with Wall Street veterans.

Three of his top advisers -- Mnuchin, chief economic adviser Gary Cohn and chief strategist Steve Bannon -- worked at investment bank Goldman Sachs. (There are more Goldman alums in the second rung of key positions).

Along the way, Trump's populist campaign rhetoric has been transformed into a more pro-business, center-right administration.

Among the recommendations in Monday's report: give Treasury greater power to oversee bank regulators; require regulatory agencies to analyze the cost of new rules; and strip the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. of its responsibility to oversee banks' plans for how they should be unwound if they fail.

The report also endorsed the idea of forcing the Federal Reserve to make its stress tests of the largest U.S. banks more transparent. Stress tests are simulations regulators run to gauge a bank's ability to weather a downturn.

The administration's report immediately drew applause from trade groups representing the biggest banks.

Sally Miller, chief executive of the Institute of International Bankers, hailed it as a "thoughtful, well-reasoned, common-sense approach" in addressing concerns tied to post-crisis financial rules.

An accounting provided by Senator Sherrod Brown's office, the top Democrat on the Senate Banking Committee, the agency consulted with 224 bank industry groups versus 13 consumers advocate organizations.

Related: Wall Street hates the Volcker Rule. Will Trump finally kill it?

Still, the administration's review left unanswered a number of pressing issues, including some dear to Wall Street.

Treasury said it would not recommend the repeal of Wall Street's most hated Dodd-Frank regulation -- the Volcker rule, which bans banks from making risky bets with taxpayer-backed money.

Mnuchin has previously expressed support for the rule's goal, saying that "proprietary trading does not belong" in banks with a government backstop. But he's been clear he believes the Volcker rule should be simpler and may have gone too far in reducing trading.

Since then, he's directed five regulatory agencies to revisit it.

The administration also refrained from diving into its plans to scrap a Dodd-Frank provision that gives the government power to unwind failing banks. That rule is the subject of a separate report due in October.

The GOP bill takes away regulators' ability to oversee that process. Republicans argue that Dodd-Frank codifies future government bailouts of big banks.

Mnuchin has criticized the provision, but he has also said that Treasury has yet to reach a final decision. During a Senate Banking Committee hearing in May, he acknowledged that the current bankruptcy code wouldn't be enough to unwind a big bank.

The Treasury report also didn't weigh in on Trump's calls for a "21st century Glass-Steagall Act," a reference to the Depression-era law that separates commercial and investment banking. The notion of restoring Glass-Steagall is anathema to banks and their lobbyists.

Mnuchin last month tried to clarify the president's endorsement, saying he did not support strict limits that require breaking up the big banks.