Would the Republican health care plan cut Medicaid spending or not?

Trump administration officials and Republican lawmakers say that Congress is not cutting Medicaid, just slowing its growth rate to strengthen the program.

Health Secretary Tom Price told CNN this week: "The fact of the matter is the Medicaid proposal in the Senate bill goes up every single year that the plan is in place."

And President Trump himself tweeted that Medicaid spending would rise under the Senate plan, a vote on which was delayed earlier this week after it became clear that the GOP couldn't muster the support it needed for passage.

Yet, the Congressional Budget Office says the Senate bill would reduce federal spending on Medicaid by a total of $772 billion by 2026, and the House's legislation by $834 billion over that time.

That would leave between 14 million and 15 million fewer people insured under the program by 2026, the non-partisan agency said.

Democratic lawmakers, consumer advocates and health policy experts have decried the bill as gutting the nation's largest health care program, which covers 70 million low-income children, adults, elderly and disabled Americans. Even some Republican senators say they can't support the legislation because of the harm it would wreak in their states.

The National Association of Medicaid Directors Board of Directors said this week that "no amount of administrative or regulatory flexibility can compensate for the federal spending reductions that would occur as a result of this bill."

Related: Senate GOP health bill would slash Medicaid. Here's how.

Here's the deal:

Republicans would end enhanced federal funding for Medicaid expansion and curtail federal support for the overall program by turning it into a block grant or per capita cap program. This means states would receive a fixed amount of funds from Washington D.C., rather than an open checkbook based on how much they spend. (On average, the federal government foots 63% of the nation's Medicaid bills, while states pick up the rest.)

Also, the bills would slow the growth of future spending by pegging annual increases to an inflation measure. The House would tie yearly boosts to the medical inflation rate, while the Senate would increase funding by the standard inflation rate, which is considerably lower.

Medicaid costs are expected to rise 4.4% annually over the next 10 years, on average, according to CBO. But the medical inflation rate is projected to grow only 3.7% and the standard inflation rate at 2.4%.

Related: Even the middle class would feel GOP squeeze on nursing home care

So what would happen?

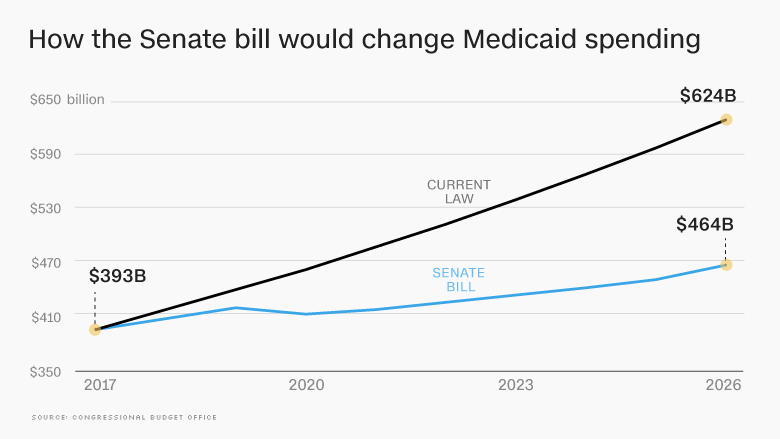

It's true that federal spending would rise over the next 10 years under both health care bills. Take the Senate bill: The CBO estimates that the federal government would shell out $393 billion for Medicaid next year and $464 billion in 2026.

However, that's 26% less -- or roughly $160 billion -- than the feds would spend on the safety net program under current law that year.

Spending would drop by about 35% in 2036, compared to current law, according to a separate CBO report released Thursday. The analysis, requested by Democratic leaders, showed that the gap in federal support would widen after 2025, when the annual growth in Medicaid would start being pegged to the standard inflation rate.

This reduction is what has Medicaid supporters up in arms. They say the increase in federal support will not keep up with the growth in costs, and the problem will only get worse over time.

There's no way that cash-strapped states can make up the difference, so they would be forced to tighten enrollment, eliminate benefits or cut provider rates, supporters say.

Related: Who gets hurt and who gets helped by the Senate health care bill

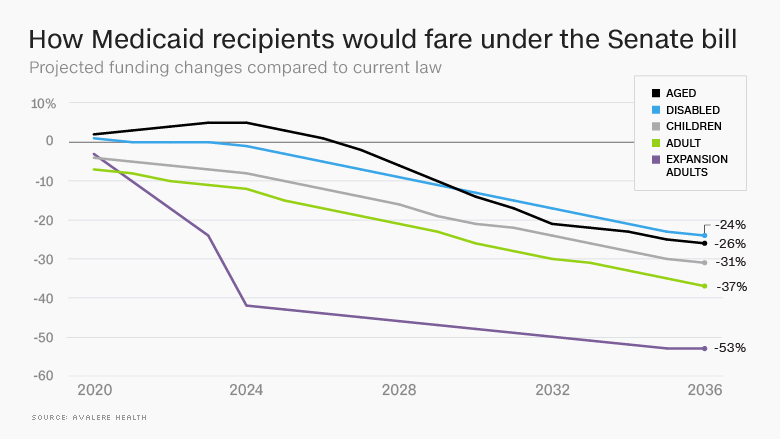

Each group covered by Medicaid would see major reductions in their federal funding -- ranging from 24% for the disabled to 53% for adults covered under Medicaid expansion -- by 2036, according to Avalere Health, a consulting firm.

Lawmakers are now meeting behind closed doors to hash out a compromise that might get enough members to support the legislation. Revising their plans for Medicaid is at the top of the list.