Reported by Sara O’Brien & Laurie Segall

Women's stories reveal systemic sexual harassment in tech

-

-

6:47

6:47

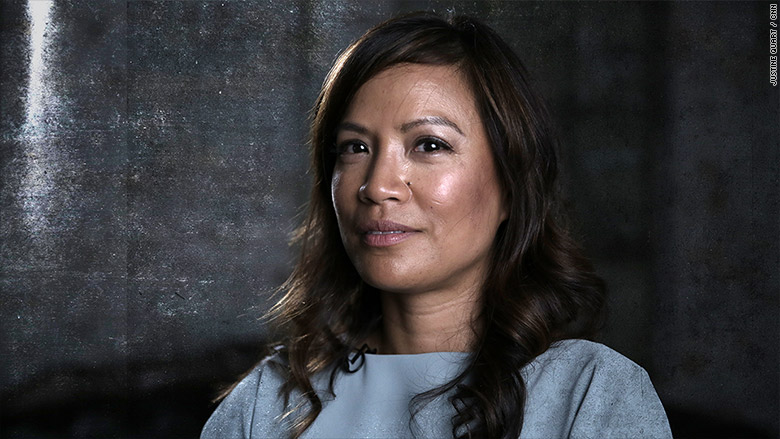

It was 2001 during the dotcom crash, and Cecilia Pagkalinawan had a tough choice: Raise more money for her startup or let 26 employees go. She set up a meeting with a powerful venture capitalist in New York City, who she hoped would want to invest.

Pagkalinawan said the investor scheduled the meeting at an expensive restaurant. When she arrived, he ordered a $5,000 bottle of wine. She said he refused to accept no for an answer when she said she didn't drink.

Pagkalinawan said she can't recall how many times her glass was refilled. She does, however, remember the VC touching her leg, leaning over to kiss her, and telling her that he wanted to take care of her. She excused herself to the restroom, vomited, then called a friend and fled the restaurant.

Pagkalinawan has stayed silent about the encounter for more than a decade. But in recent weeks, a flood of all-too similiar stories about sexual harassment in Silicon Valley has reopened the old wounds — and inspired her to speak up.

"I can't believe after all these years it still hurts, you know?" she told CNN Tech.

The tide is starting to turn. In the past three weeks, two powerful Silicon Valley investors — 500 Startups' Dave McClure and Binary Capital's Justin Caldbeck — have resigned over allegations of sexual harassment. Both men have issued broad apologies for their behavior. As a result, multiple women have come forward to share their own experiences about working in an industry rife with sexism and harassment.

2:08

CNN Tech talked to six of these women about tech's systemic problems — and their hopes for the future of the industry.

Entrepreneur Bea Arthur was going over financial projections with an investor when he exposed himself to her.

"He stood up, and he pulled out his erect penis," she said. "It was awkward. It was uncomfortable. It was unfair."

Arthur said she tried to shrug off the awkwardness and never confronted him about it. "He probably thinks we're close friends," she said.

There's a frequently touted ethos that investors fund people, not just ideas. Because of that, investors need to get to know founders, according to entrepreneur Susan Ho, one of the women who went public about Caldbeck's alleged harassment.

1:36

"Much of that building of camaraderie happens in social settings," said Ho. "It happens over drinks. It happens over dinner."

Ho said there's nothing wrong with drinks or dinner, but the undefined relationship between entrepreneurs and investors — coupled with the industry's power dynamics — can complicate those casual meetings. It's especially complex for female founders, as men control the vast majority of capital. 89% of those making investment decisions at the top 72 firms are male, according to one survey. And in 2016, VCs put $64.9 billion into male-founded startups, compared to $1.5 billion into female-founded startups, according to new data from PitchBook.

This means female founders are primarily pitching men. And it's typical to meet investors in informal locations — restaurants, bars, coffee shops. It's also the norm to take meetings after working hours, especially for younger founders.

Arthur said that when the investor flashed her, she felt a "very deep and sudden and overwhelming sense of shame. Like, 'I'm stupid. I should have known this was going to happen. Why did I think he was taking me seriously?'"

Lisa Wang, cofounder of female entrepreneur collective SheWorx, was caught off guard at Consumer Electronics Show this year when a pitch meeting quickly went south. "We're sitting at the Starbucks, and he grabs my face and tries to make out with me, and I push him back in surprise, and just didn't know what to do, because he continued to try again, and was so aggressive."

Wang said the investor tried to follow her to her hotel room. "I said, 'I'm not getting in this elevator until you leave."

"If [the male investor] looks at another man, he sees them as an opportunity, a colleague, a peer, a mentor," said Arthur, who founded a mental health startup. But if you're a female founder, "he just sees you as a woman first."

Three weeks ago, The Information published a story in which six women accused investor Justin Caldbeck of sexual harassment. Three of the women came forward anonymously, but three put their names by their accusations. That's a rarity in Silicon Valley where the prevailing advice is to stay silent and avoid repercussions — both financial and emotional.

There's fear of earning a reputation as someone who's difficult to work with, which could make it difficult to secure funding. Investors may avoid financing a company with a founder they don't "trust" if they're nervous she may speak out about their behavior, too. That's helped keep those who've behaved inappropriately in positions of power, according to Arthur.

"People at the top stay at the top, and they understand each other," she said. "They have vouched and, more importantly, covered for each other."

3:35

Even so, Susan Ho and Leiti Hsu, cofounders of travel startup Journy, came forward with their stories about Caldbeck.

"When you talk about sexual harassment in tech or in any other industry, it's like dropping a nuclear bomb on your career," Ho told CNN Tech. "That fear of retaliation, of it impacting your business in some way, is so, so real. We have a financial responsibility to do what's best for our business, and if speaking out is going to harm our business, is that OK?"

It was the decision to go public — and have their names attached to the accusations — that set off a firestorm in Silicon Valley. Countless other women have come forward since then, sharing their own stories of sexism in tech.

"Ultimately, we spoke about it in hopes that at the very least, there would be an article high enough on Google that the next time [Caldbeck] met with a female founder, she would Google him and see this article and at least be extra on her guard or think twice before meeting him," Ho said. "[Caldbeck] preyed on a group of women who [he] felt were too afraid, or not in the position to speak out against [his] behavior, and [he] was wrong."

The emotional repercussions of speaking out are something Gesche Haas, founder of Dreamers // Doers, is all too familiar with. Haas went public with sexual harassment allegations against investor Pavel Curda in 2014. While at a conference, he propositioned her in an email that read, "I will not leave Berlin without having sex with you. Deal?" Curda first tweeted that his email account had been hacked, but apologized one day later claiming he was drunk.

She's been picked apart on the Internet and received death threats on social media.

"I got people tweeting [at me], 'I will cut your throat you f***ing c***,'" she said. People have accused her of being "a damsel in distress," suggesting she spoke out for "attention."

Despite it all, Haas said she stands by her decision. "The risk of not saying anything, living with this forever is way worse. I felt because I had so much evidence, it was so clear cut. I had a responsibility to say something," she said.

Still, three of the women CNN Tech spoke to — Arthur, Pagkalinawan and Wang — declined to publicly name the men they say harassed them. This was partly because they didn't have any tangible evidence that could confirm the specific encounter.

"The most difficult part of reporting is ... the fear of being in a compromised position if you are the only one to speak up about the offender," added Wang.

When Ho and Hsu spoke out, they were concerned their stories wouldn't appropriately outrage people in the tech industry. They credit LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman for focusing people's attention on it.

One day after The Information's story came out, Hoffman published a post on LinkedIn that called on investors to sign a "decency pledge." He proposed that tech actively work on building an industry-wide HR function so venture capitalists who engage in inappropriate behavior face consequences.

"It took [Hoffman's post] to really give the issue weight," said Ho. "It's my hope in the future that the accounts of countless women is going to be enough to give an issue like this weight."

There are early signs that companies may start taking swifter action once alerted to harassment. This week, early stage VC firm Ignition Partners said its managing partner, Frank Artale, had resigned over misconduct. The firm released a statement, disclosing that they'd investigated a report of "inappropriate conduct" by Artale in 2016. Artale has not publicly released a statement about his resignation. The firm did not reply to CNN Tech's request for further comment.

According to Nathalie Molina Niño, cofounder of female-focused BRAVA Investments, pledges may be a start, but they certainly aren't a cure-all. "Women can't pay the rent with symbols and PR gestures. What's needed is real outcomes, and it starts by accepting we, in all corners of tech, have a systemic problem," she wrote.

3:08

Niño says until the gender gap is actually closed at tech companies, the "institutional dysfunction" will still exist. She argues for outcomes over optics, which she told CNN Tech includes focusing not just on funding women but on funding all types of women from all economic backgrounds. "Women exist. We aren't the exception, we're the norm," she said. "Yet places that treat us as humans are, in fact, outliers."

Sixteen years after Pagkalinawan was sexually harassed, she said she was disheartened to hear that little has changed.

"It really, really saddened me that this is happening [so] prevalently," she said. "I really think sometimes that they don't look at us as if we're humans, let alone their equals. I want to look at them in the eye and say, 'How would you deal with this if it happened to your wife or your daughter and [yet] you did it yourself?'"

We're still reporting this story. Tell us your personal experience as a woman working in tech. Email sara.obrien@turner.com.