A word like "fresh" can be a signal that a young girl is being trafficked. Finding it in advertising could lead to saving someone's life.

Human traffickers rely on the internet to advertise and maintain criminal enterprises. The Global Emancipation Network collects and analyzes the digital breadcrumbs they leave behind to help find victims and stop traffickers.

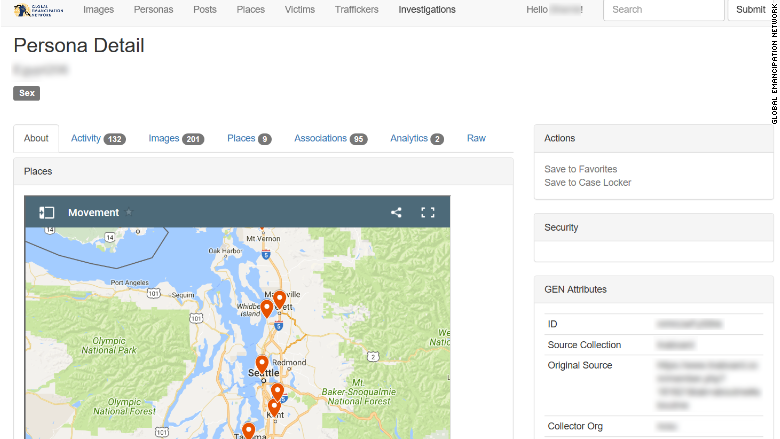

The organization uses data analytics to find, study, and make connections between people and the information they share online. With corporate partners including Microsoft (MSFT), Splunk, and Recorded Future, the volunteer-run organization has created a searchable database and tool to find and analyze trafficking data.

"There has to be more that we can do to identify victims, rescue them, hope they don't get revictimized. And then to stop and punish those traffickers," said Sherrie Caltagirone, founder and executive director of GEN. "Right now, they operate with impunity online."

Their external platform, called Minerva, is currently in beta, and the plan is to eventually provide it free to law enforcement and victim service providers. It includes image processing, data analytics, bitcoin analysis, and public records enrichment. Police will be able to use it to search for things like advertisements, phone numbers, or websites traffickers use.

Internally, GEN uses the data it collects to look for patterns human trafficking and study global trends. There are tens of millions of people trafficked each year, and according to the International Labour Organization, 21 million people are victims of forced labor worldwide. The UN estimates children make up about a third of global trafficking victims.

There are currently a handful of nonprofits that use data to track human trafficking, including Thorn and the Polaris Project. Caltagirone says GEN is unique because it collects data about all types of human trafficking from 22 countries and 80 jurisdictions.

Related: Hacker creates organization to unmask child predators

GEN scrapes data from a variety of sources, including Craigslist, Backpage, and dark web sites.

Splunk, a data analysis platform and supporter of the organization, donated its technology to GEN. It can index the scraped information and look for suspicious signals in the data by analyzing keywords, phone numbers, geographic data, or usernames. For instance, ads are deemed suspicious if they contain the same phone number but pop up in two different states.

GEN's platform also studies the language used in advertising, including emoji or text embedded in images. One sign of an underage sex trafficking victim could be words like "lolita" and "fresh" in an advertisement. Studying language and data shared in ads also helps differentiate between posts from independent sex workers and those that are likely to be sex-trafficking victims.

Though her group analyzes all types of human trafficking, it is more difficult to spot labor trafficking than sex trafficking.

Andrew Lewman, vice president of OWL Cybersecurity, says human traffickers will frequently start on Facebook to advertise smuggling services, then switch to encrypted chat apps and use anonymity tools like Tor to protect communications and information.

"One way traffickers uses the internet and darknet is to buy, sell, or coordinate people," Lewman said. Like any business, much of it relies on the web.

Lewman, who served on President Obama's tech and trafficking task force, provides GEN with indexes of data. The firm scrapes 400 million pages every few months, he says, most coming from the dark web, and shares that data with GEN. The organization or law enforcement can then run their own queries on it, like searching for ads or usernames from an investigation.

"Some of the techniques we do we don't advertise, because we don't want traffickers to find out about it and stop doing the thing they're doing that allows us to find them," Caltagirone said.

Caltagirone, who has worked in anti-human trafficking her entire adult life, has spent hundreds of hours talking to law enforcement. She recently tested the platform with one U.S. District Attorney in an ongoing investigation of an escort review forum. The DA wanted a list of some users on the forum, what other sites they were on, what criminal activity they engaged in, and photos shared with their posts. Then law enforcement could cross-reference the usernames and phone numbers to other locations online.

The group has also studied whether or not site shutdowns -- a traditional law enforcement technique that makes a website inaccessible -- actually prevent bad behavior. Her organization studied web traffic data after Backpage closed its adult advertising section, and found that it doesn't. Users simply went elsewhere.

Ultimately the platform will be free to law enforcement, funded entirely by donations. Many jurisdictions don't have the budget to pay for technical tools, or have dedicated human trafficking units. Those are the clients Caltagirone wants to target first.

But beyond cash-strapped police departments, making the platform free is an ethical issue.

"Trafficking victims have already had their lives destroyed, and they've already had people make ungodly sums of money off their exploitation," she said. "We say the buck, literally, stops here."