Americans dread flying. But relief may be coming.

That's if Montreal-based Bombardier's C Series airliner doesn't first trigger an all-out trade war between the U.S. and Canada.

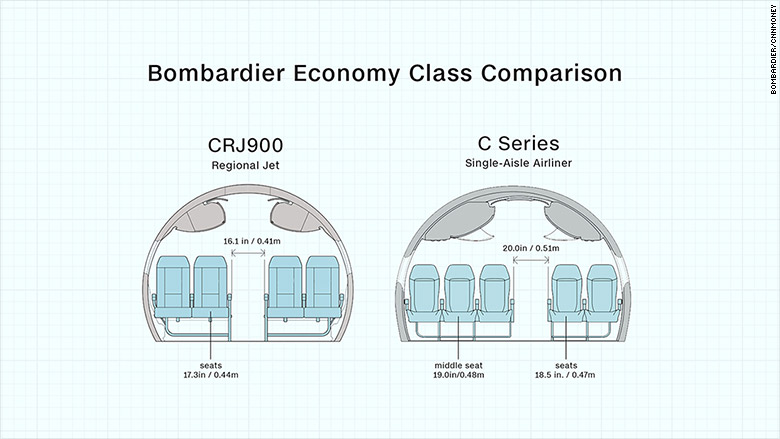

The plane's roughly 110-seat cabin is designed with an aisle wide enough to maneuver around the drink cart, overhead bins big enough to fit your bag, larger windows and half as many middle seats as bigger aircraft -- and even those are an inch wider. It's also significantly quieter and more fuel efficient than the jets it replaces.

Delta Air Lines plans to replace its smaller regional jets with more spacious C Series on flights up to 1,500 nautical miles -- or about three hours of flying time.

The C Series has been flying passengers in Europe since June 2016, and starting next year, the Bombardier CS100 will start appearing at airports around the U.S.

But Boeing, America's largest exporter and sole U.S. producer of commercial airliners, is suing Bombardier. At issue is whether funds Bombardier received from the Canadian government to stay afloat allowed the plane maker to sell to Delta for what Boeing alleges were "absurdly low prices."

Boeing maintains the government support helped its Canadian rival establish the all-new airliner at the expense of Boeing's own 737 jets. It claims that Bombardier is selling each C Series jet to Delta for $19.6 million. That's not accurate, said Delta.

The jet's list price is nearly $80 million, but steep discounts are common.

The U.S. International Trade Commission, an arm of the Commerce Department, is expected to make the first of two rulings on the dispute as early as September 26.

Bombardier refutes the claims. It says a deal with Delta for up to 125 planes was standard practice for an industry that wants big names to endorse its products. Delta said the complaint is "without merit."

Related: Justin Trudeau warns Boeing over trade dispute

Boeing has recommended a 160% tariff on the jet, paid by Delta or any U.S. airline importing the aircraft. That would mean that for every dollar Delta pays Bombardier for the jet, it would have to write a check to the U.S. Treasury for another $1.60.

And while Boeing leaders emphasize its grievance should be limited to this one deal for this one airplane, the suit is widely considered an existential threat to the Canadian plane maker should it be shut out of U.S. -- the largest aviation market in the world.

International implications

The dispute has drawn in the leaders of Canada and the United Kingdom and now threatens to shoot down a $5.2 billion Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter deal with the Royal Canadian Air Force if the case isn't dropped or settled out of the ITC.

"We won't do business with a company that's busy trying to sue us and put our aerospace workers out of business," said Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Monday. Bombardier's aerospace division employs 28,500 worldwide, including 4,000 in Northern Ireland where the jet's wings are manufactured.

And more than half of the jet is manufactured in the U.S., including its Pratt & Whitney engines. That has drawn letters of support by members of Congress and even U.S. airlines like JetBlue Airways and Spirit Airlines, which want a viable third competitor to Boeing and Airbus.

Related: U.K. to Trump: You can save jobs by fixing Boeing-Bombardier fight

If the deal survives, Bombardier says any tariff would negate the operating savings the C Series brings and be passed along to passengers in the form of higher fares.

The spat is part of larger trade tensions brewing between the U.S. and Canada. The Trump Administration already slapped the Canadian timber industry with a 20% tariff on imports.

Barely Survived Its Birth

To understand how this case came to be, you first need to understand that this tiny jetliner nearly killed its maker.

Launched in 2008, the C Series was supposed to be ready in 2013. But Bombardier was beset by engine and software issues and the sheer complexity of designing an all new airplane. It was delayed by three years and went billions of dollars over budget.

Bombardier required a radical overhaul to stay afloat. The scion of the family-owned business stepped aside. An outside CEO came in. Thousands were laid off. The Quebec provincial government pumped $1 billion into the company and the federal government handed over about $282 million in loans. The C Series is now 49.5% owned by the taxpayers of Quebec.

Boeing alleges that the state aid to keep the lights on at Bombardier allowed the company to sharply cut the C Series price tag for Delta.

Bombardier at the time needed a big win. The C Series had sold poorly for years, muscled out by Boeing and Airbus. The airline lost out on a chance to join United Airlines' fleet earlier in 2016. The Delta deal for up to 125 jets was widely considered a must-win for the airline.

And it was. By the time the ink was dry in March 2016, Bombardier's CEO Alain Bellemare conceded to The Wall Street Journal: "We knew that we would need to be competitive to get some marquee airlines."

"So we've done just that," he said.

Delta's Deal

Delta knocked on the Canadian airplane maker's door and got, what Boeing has alleged, a deal so good that it violated international trade laws.

Delta's price tag for the planes isn't a mystery. It was disclosed as part of the ITC investigation but redacted from public documents reviewed by CNN. Two people familiar with the deal said each plane was in the "high $20 millions."

"These campaigns help determine whether a new airplane will thrive or die. That's why Bombardier is willing to lose millions of dollars per plane on this sale," said Boeing Vice Chairman Ray Conner in testimony to the ITC. "That's what Bombardier bought with Canada's subsidies -- a seal of approval for the C Series jets."

But does the price tag for those jets - which are smaller than anything Boeing has made since 2006 - constitute illegal dumping? And was Boeing harmed by the deal?

Adam Pilarski, Senior Vice President at aerospace consultancy Avitas said politics, not planes, are motivating the suit. Boeing has more than 4,400 737s on order and is in the process of increasing production to meet skyrocketing demand.

Further, Pilarski said Boeing has no idea what price Delta paid for the jets nor does it know how much it costs Bombardier to make each jet.

Nor does Bombardier. The Canadian plane maker has delivered fewer than 20 planes. And tallying production costs of something as advanced as a jetliner takes a lot of repetition before a "learning curve" on spending is clear, said Pilarski, former chief economist for McDonnell Douglas.

"This is total Looney Tunes, it doesn't make any frickin' sense whatsoever," said Pilarski, former chief economist for McDonnell Douglas. "You cannot establish the facts that Boeing asserts."