The "King of Debt" has plenty of power, but he can't make Puerto Rico's mountain of debt magically disappear.

President Trump, who gave himself the royal moniker during the 2016 campaign, told Fox News' Geraldo Rivera that "we will have to wipe out" Puerto Rico's crushing debt load.

Trump's dramatic statement spooked the market. The price of some Puerto Rican bonds crashed 15% Wednesday, suggesting investors are even more worried about being repaid. U.S. bond insurers like MBIA (MBI)also took a hit.

But analysts say Trump's words shouldn't be taken literally. He doesn't have the legal authority to erase Puerto Rico's $73 billion in debt.

"Trump does not have the ability to wave a magic wand and wipe out the debt," said Cate Long, an expert on Puerto Rican debt and founder of research firm Puerto Rico Clearinghouse.

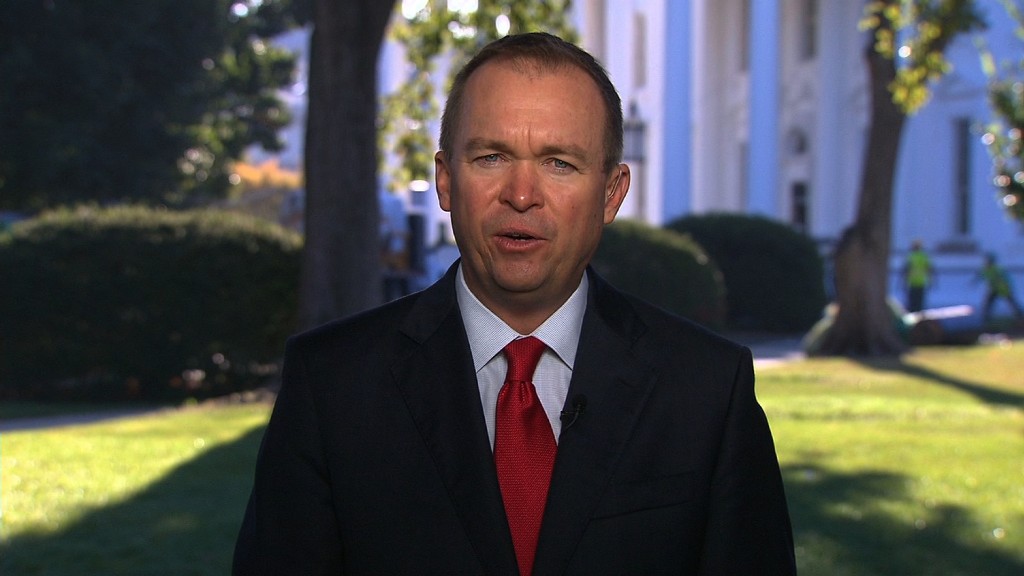

Mick Mulvaney, Trump's own budget director, told CNN that Trump's comments shouldn't be taken "word for word."

"Threats to wipe out bondholders appear more bombastic than actionable," Isaac Boltansky, senior policy analyst at Compass Point Research & Trading, wrote in a report. He said the odds of that happening are "minute."

Puerto Rico's constitution requires the government to pay interest on its debt before any other expense.

"It's not as if Trump can say, 'I don't like Puerto Rico's constitution, so I'm going to override it,'" Long said.

Related: Who owns Puerto Rico's debt? You do

Trump could help break logjam

But that's not to say Trump can't play a role in trying to solve the very real debt problems facing Puerto Rico after it filed the largest municipal bankruptcy ever in May.

Trump may be signaling a desire to move along a bankruptcy process that is going so slowly that it's casting a shadow over Puerto Rico's difficult recovery from Hurricane Maria. Puerto Rico is effectively cut off from borrowing more money as it sorts out its bankruptcy.

Up until now, this messy process has played out as a legal war. Dozens of court cases have been filed by Puerto Rico's various bondholders -- and these investors aren't always on the same page about what they want.

But Trump, who has ample experience with bankruptcy during his own career, could try to break the logjam by forcing the parties to negotiate a deal.

"He is using the bully pulpit to try to affect the outcome and speed the process along because the longer it goes on, the more uncertain it makes Puerto Rico's recovery prospects," said Greg Clark, head of municipal research at Debtwire.

Beyond the influence of the White House, Trump has leverage in the form of federal dollars for disaster relief. The White House plans to ask Congress for $29 billion for hurricane relief, and some of that money is likely to be directed toward Puerto Rico. While the federal aid won't eliminate Puerto Rico's debt, it could help revive the island's economy and prevent more residents from fleeing.

Related: 5 numbers that prove Puerto Rico is still in crisis

The Goldman Sachs factor

In the meantime, Trump already seems to be trying to recast the debate on Puerto Rico's debt as a populist battle between Main Street and Wall Street.

"They owe a lot of money to your friends on Wall Street," Trump told Geraldo Rivera. "I don't know if it's Goldman Sachs, but whoever it is, you can wave goodbye to that."

In reality, Main Street plays a key role here. Less than 25% of Puerto Rico's debt is held by hedge funds, according to estimates by Long. The rest is owned by individuals and mutual funds that are held by mom-and-pop investors.

Goldman Sachs (GS) is not listed in court documents as one of the major hedge funds that own Puerto Rican debt.

However, Goldman Sachs, BlackRock (BLK), OppenheimerFunds, Franklin Templeton and many firms do manage mutual funds that have invested in Puerto Rican bonds on behalf of individual investors.

In any case, analysts warned that Trump's calls to wipe out Puerto Rico's debt could backfire if they hurt confidence in the municipal bond market.

Fears that Trump could try to erase other debts would force borrowing costs to raise, making it harder to raise money for infrastructure and other projects.

"This 'Geraldo risk premium' would increase municipal financing costs and thereby directly impact citizens," said Boltansky.