Venezuela is deep into a humanitarian crisis and it owes far more money than it has in the bank.

Dozens of U.S. mutual funds and big banks, which invest on behalf of millions of Americans, own portions of the debt.

Venezuela was declared in default late Monday by S&P Global Ratings after a 30-day grace period expired for a payment that was due in October. That could set in motion an ugly series of events that would exacerbate the country's humanitarian crisis.

Owning Venezuela's debt has become a divisive issue. Some critics say that by buying the debt, investors are providing a lifeline of support to President Nicolas Maduro, who has been labeled a "dictator" by the Trump administration. They argue that the government has prioritized paying bondholders instead of feeding and aiding its people. Medical shortages have caused children to die in hospitals and food shortages make millions of people go hungry.

Related: Venezuela just defaulted, moving deeper into crisis

Experts on all sides say government policies, not the debt, are to blame for the suffering. The question is whether buying the bonds are allows the government to continue its crippling policies.

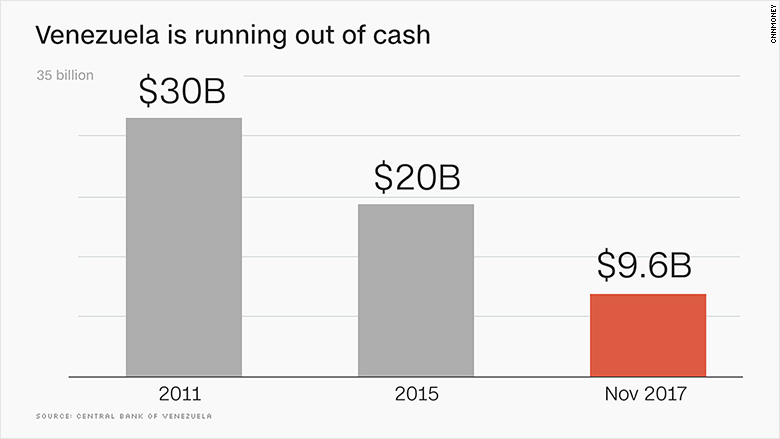

Venezuela owes over $60 billion to bondholders. The country's central bank has only $9.6 billion left.

Harvard professor Ricardo Hausmann, who served as a Venezuelan minister in 1990s, calls Venezuelan debt "hunger bonds."

"If you are a decent human being, investing in Venezuelan bonds should make you feel mildly nauseous," Hausmann wrote.

Related: Venezuela: We can't pay our debts anymore

Many Venezuelan bonds aren't purchased directly from the government, which would finance the regime. In fact, as of August, the Trump administration made that illegal. Instead, bond traders buy them from other traders on the "secondary" market, and those funds go the bank or investment firm on the other side of the transaction, not to the Venezuelan government.

Some portfolio managers who own Venezuelan debt condemn Maduro's regime and all its policies.

"We're certainly not propping up this regime," says Michael Conelius, portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price who oversees a bond fund that includes Venezuelan debt. "Bondholders are as much a thorn in the side of the regime as anything else."

All sides agreed that Venezuela's default was only a matter of time. And its debt is held by millions of Americans who have 401(k) accounts, according to data from Morningstar and Market Axess.

These are the top institutional holders of Venezuelan debt -- bonds sold by both the government and state-owned oil company PDVSA:

-- Fidelity Investments: $572 million

-- T. Rowe Price: $370 million

-- BlackRock iShares: $222 million

-- Goldman Sachs $187 million

-- Invesco Powershares: $113 million

Fidelity and Invesco declined to comment; BlackRock didn't respond to CNNMoney. Goldman bought bonds soon after the Venezuelan government issued them in May, which sparked huge public backlash. A Goldman spokesperson said at the time that it hopes to see a change of government and policies.

Fidelity's website says it is the top 401(k) provider in the United States with 67.2 million customer accounts. But it's unclear how many of those accounts have money in funds that contain Venezuelan debt. The same goes for the other investing firms.

Fidelity's "New Market Income Fund" holds $252 million in Venezuelan debt, according to an analysis of the most recent prospectus by CNNMoney. It makes up a sliver of the total fund, but some bonds pay hefty interest to investors, as high as 13%. By comparison, interest on a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond is 2.3%.

Related: Venezuelan leaders tell hungry citizens to eat rabbits

Dozens of other mutual funds and investment banks also own the country's bonds.

One caveat: The Morningstar and Market Axess data don't include hedge funds or international investors who don't have to disclose their holdings. Market Axess cautions that much more of Venezuela's debt could be held by those entities than the mutual funds.

Since Maduro announced plans to restructure the bonds -- something investors took to mean he would stop paying -- bond prices have tanked. A PDVSA bond that matures in 2022 plunged to 28 cents on the dollar from 48 cents after the announcement, according to Market Axess BondTicker.