Who are America's Dreamers?

They are the hundreds of thousands of young undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children -- and they now face a very uncertain future.

President Donald Trump in September rescinded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which enabled Dreamers who signed up to come out from the shadows and attend school, get a job and gain protection from deportation.

Ending the DACA program, which was enacted through an executive order by President Barack Obama in 2012, could upend the lives of the nearly 689,000 15- to 36-year olds who gained DACA status.

But there is still some hope for DACA recipients. The Trump administration gave Congress until March 5 to enact an alternative before those protected under the program lose their ability to work, study and live without fear in the U.S.

Related: DACA in flux: 5 things business owners need to know

Should Congress fail to meet the deadline, those with DACA status will lose their work authorization and their employers may be forced to lay them off.

Many graduating high schoolers may no longer be able to attend college. And all DACA status holders would lose their identification cards, which in many states allows them to drive legally.

This is a significant problem, said Randy Kapps, director of research with Migration Policy Institute. "If they get caught driving without a license, they can be arrested and held in ICE custody and potentially face deportation," he said.

While their future in the U.S. now hangs in the balance, a report from the Migration Policy Institute provides a detailed profile of Dreamers with DACA status. Here are some of the key findings:

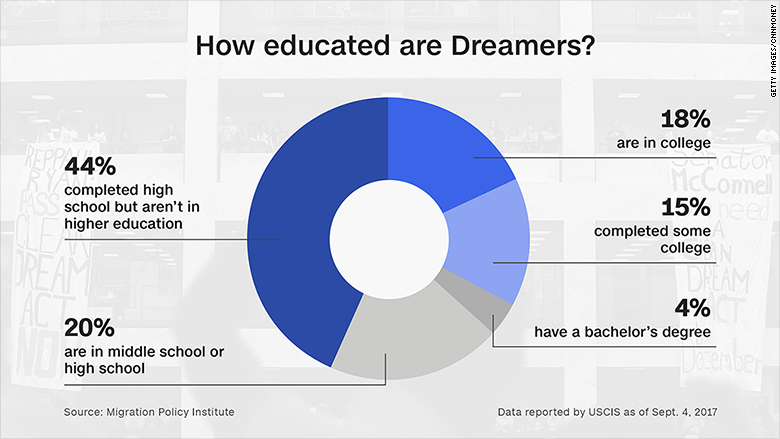

In order to qualify for DACA status, a person must either be enrolled in school, already have a high school diploma or have a GED. This means almost all of those covered by DACA are high-school educated.

Of the 689,800 DACA holders, 20% are currently in middle or high school and a little less than half (44%) have graduated high school, but have not enrolled in college.

Related: DACA students are worried. The clock is ticking

Another 18% of DACA recipients are enrolled in college, making them almost as likely to enroll in college as the average American in the same age group. The difference is that just 4% of DACA recipients have completed a bachelor's degree -- a much smaller percentage than their American peers.

The report also found that one out of three DACA recipients who is enrolled in school also holds a job, which is on par with other young American adults.

Just over half (55%) of DACA recipients -- about 400,000 -- are working, while most of the rest are in school, unemployed or not in the labor force, the report said.

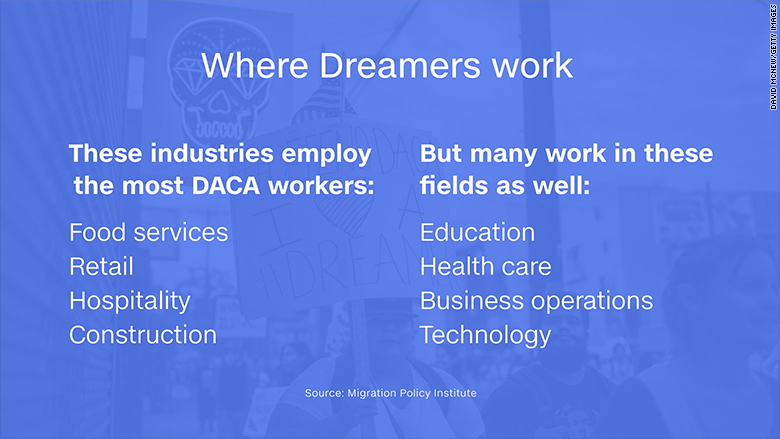

And Dreamers are employed across a variety of service and professional jobs.

"What our research shows is that DACA recipients are largely a working class population," said Kapps.

"This may come as a surprise to people that so many of them are in these mid-skill jobs," he said.

While a large number of Dreamers hold retail jobs or work in the food services or hospitality industries, many are also teachers, health care providers, business managers and social workers.

The report found that about 9,000 are employed as teachers, while some 14,000 are working as health care practitioner and support jobs. Another 14,000 work as managers.

"The jobs they hold are generally better compared to someone who is undocumented and not eligible for DACA," said Kapps.

The report said DACA recipients are half as likely to work in construction as compared to undocumented individuals who don't have DACA status.

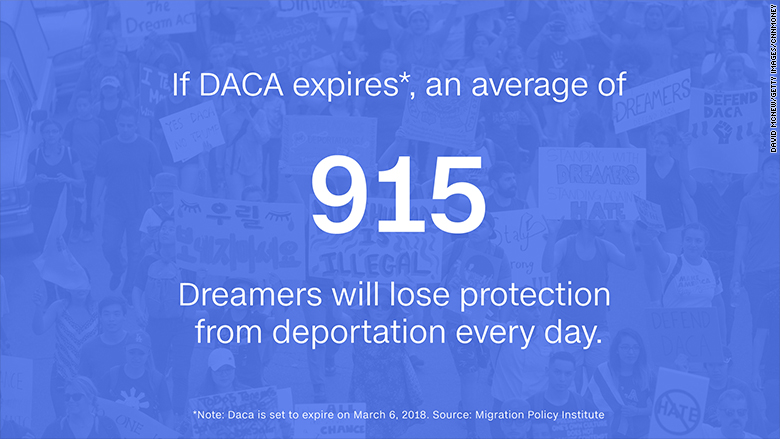

Should Congress fail to act by the March 5 deadline, the Migration Policy Institute estimates that an average of 915 DACA holders every day will lose their ability to work and their protection from deportation every day between March 6, 2018 through March 20, 2020.

Related: These men and women will be out of work if Trump repeals DACA

"The stakes are high for several hundred thousand immigrants who could lose their work authorization and also be at risk of deportation," said Kapps. "The same holds true for the many businesses that employ them, and for the communities where they live."