Poor Americans would lose billions of dollars worth of federal benefits under the Senate GOP tax bill, according to a new Congressional Budget Office report.

This is largely because the legislation would eliminate the individual mandate, which requires nearly all Americans to get health insurance or pay a penalty. This would result in 13 million fewer people having coverage in 2027, the CBO found.

Many of the folks who would forgo coverage would have lower or moderate incomes and would have qualified for Medicaid or federal help paying their premiums or out-of-pocket health expenses, CBO found.

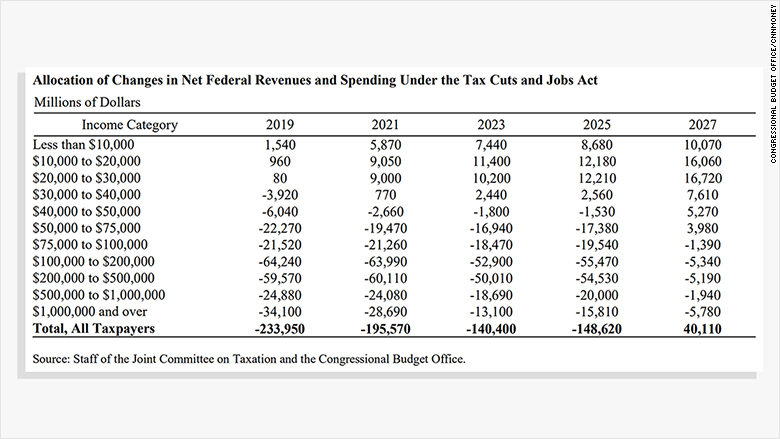

Those earning less than $40,000 a year would be worse off in 2025, when the bill's provisions would mostly be in effect, according to the report released Sunday. On the flip side, those with higher incomes would enjoy tax breaks.

Related: Senate tax cuts are permanent for businesses but temporary for you

The Senate legislation would make multiple changes to the tax code, but the vast majority of individual tax cuts would expire after 2025. These include changing the rates on individual tax brackets, nearly doubling the standard deduction, eliminating personal exemptions, expanding the child tax credit and repealing the state and local tax deduction.

In 2027, after the individual income tax provisions expire, more middle class Americans will get hit, the CBO found. Only those earning more than $75,000 will see their federal tax levy drop.

Other analyses by independent think tanks have also found that the bill's benefits are weighted toward those higher up the income ladder.

Related: How would the middle class fare under the Senate tax bill?

Republican lawmakers have criticized the CBO's analysis, saying the bill doesn't cut federal support of Medicaid or Obamacare's subsidies.

Speaking on CNN Monday, Republican Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma criticized the agency for its "strange scoring." What CBO is labeling a tax increase is Americans choosing not to sign up for subsidized insurance, he said.

Experts are divided over the CBO's methodology. Some say it's legitimate to quantify the reduction of a government benefit, while others say it shouldn't be counted as a tax increase.

It depends in part on whether one thinks the individual mandate is needed to push people to sign up for coverage and access the benefits, said Gordon Mermin, senior research associate at the Tax Policy Center, a non-partisan research group.