Margaret Mary Basco died on June 9, 2017, at Saint Peter's Hospital in Albany, New York. She was 58.

And then, just over a month after she died, Margaret Basco submitted a comment to the Federal Communications Commission about its proposal to overturn net neutrality.

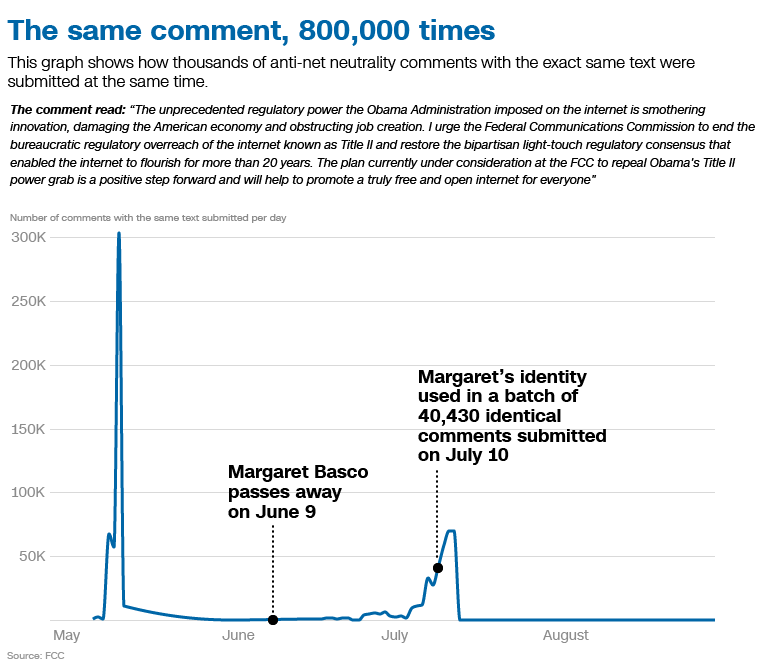

"The unprecedented regulatory power the Obama Administration imposed on the internet is smothering innovation, damaging the American economy and obstructing job creation," the comment read.

Basco's story shows how stolen personal data can be weaponized and used to interfere in the democratic process. Investigators say the identities of more than one million Americans, both dead and alive, may have been used to hijack the FCC's public comment process -- one of the few ways beyond voting that Americans can directly share their opinion with the government.

The current rules on net neutrality, adopted under the Obama administration, bar internet providers, like AT&T and Comcast, from deliberately speeding up or slowing down traffic to or from specific websites and apps. (AT&T is in the process of acquiring Time Warner, CNN's parent company.)

On Thursday, the FCC, now Republican-controlled, voted to repeal the Obama-era rules -- an outcome for which the major telecom companies have lobbied long and hard.

Related: The future of how the internet is regulated is about to change

Margaret Basco's comment was one of more than 20 million submitted to the FCC this summer after it opened a portal on its website inviting Americans to express their views on net neutrality.

The New York Attorney General's office and multiple independent studies have concluded that millions of the comments submitted, on both sides of the debate, are fake. And the New York Attorney General's office believes that an estimated one million Americans' identities were stolen and used to submit fraudulent comments.

Last month, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman encouraged New Yorkers to use a search feature his office built to check if their identities had been used to post fake comments.

Chris Basco, Margaret's son, checked for his name and found that his identity hadn't been used, and neither had his sister's nor his father's. But when he searched his late mother's name, he found the comment under her name, posted using the Albany, New York address where she lived until her death.

"My mother died on June 9th of 2017. There's no way she could have posted that comment," Chris said. And besides, he added, his mother wasn't very technically literate, and "she hated that kind of political talk."

Chris was upset by the discovery. "It was when I saw the date. That's when I really got angry. How close in proximity it was to her death."

Whoever filed the comment knew Margaret Basco's home address and her email address. They likely knew that not because they knew her but because her personal information, like that of so many Americans, was leaked in a data breach.

Basco's personal information had been exposed in January 2017 when a trove of millions of people's names, email addresses, and physical addresses that had been part of massive dataset used by a group called "River City Media" to send spam emails was leaked online.

CNN spoke to five other people whose identities were used to submit comments to the FCC without their permission, and confirmed their personal details had also been part of the River City Media database, using "Have I been Pwned?" an online database that allows people to see if their data was part of a breach.

Some of the individuals' information, including Basco's, had been exposed in previous hacks, but the River City Media database was the only set that contained all of their information.

Whoever left the comment using Basco's identity didn't even bother to make it look real. The exact same language used in that comment was submitted more than 800,000 times to the FCC. CNN spoke to people in California and Colorado whose details were also used to leave the same comment and who confirmed they had not submitted the comments.

Related: Fake comments and stolen identities prompt Democratic calls to delay net neutrality vote

Last Monday, ten days before the FCC was due to vote to repeal the current net neutrality rules, more than two dozen Democratic senators and New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman called on FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, who is pushing the change, to delay the vote until a full investigation into the fraudulent comments had been conducted.

But the revelation that the public comment process on net neutrality had been hijacked would likely not have been new to Pai.

In May, the group "Fight for the Future" sent a letter to Pai on behalf of more than 20 Americans whose identities had been used to submit comments against current net neutrality rules. Among their requests was that the FCC remove all of the comments made in their names.

The group did not receive a response from the FCC, a Fight for the Future spokesperson told CNN, and the fraudulent comments were not removed.

It's not clear who was behind the fake comments; it's possible that there were multiple actors with different motives acting independently of each other.

A report released in August that was commissioned by Broadband for America, which is backed by major telecommunications companies including AT&T and Comcast, found that the vast majority of personalized or unique comments -- that is, the comments least likely to have been faked -- were in favor of the current net neutrality rules.

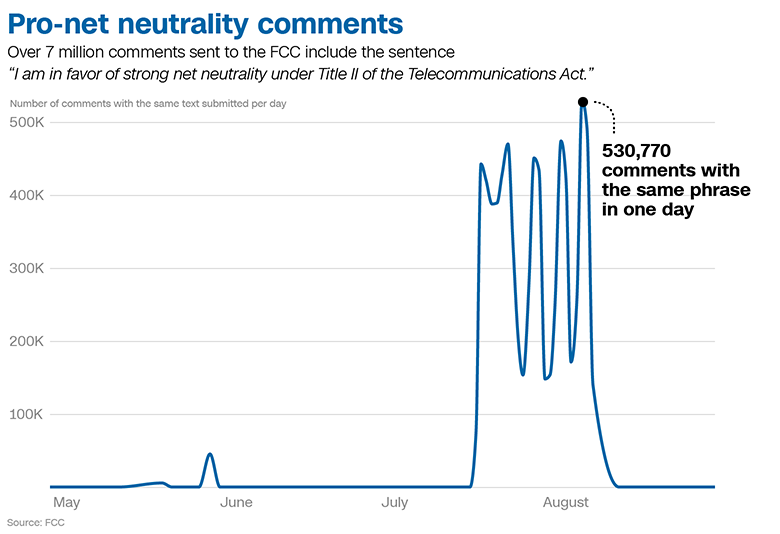

That study also found that more than 7 million comments had been submitted using temporary and disposable email addresses. Nearly half a million comments in favor of keeping existing net neutrality rules were submitted using Russian email addresses, it also found.

It's not unusual for thousands, or even millions, of identical comments to be submitted to the FCC on an issue. Advocacy groups promote letter-writing campaigns in which Americans are asked to sign their name to a pre-written letter. That's a common and accepted practice -- what isn't is using stolen identities to submit fraudulent comments.

The non-partisan Pew Research Center found that on nine different occasions, more than 75,000 comments were submitted at the same second "including identical or highly similar comments." Six of the nine occasions involved comments that were against current net neutrality rules -- the other three occasions involved pro-net neutrality comments.

All 22 million comments sent to the FCC on net neutrality, along with commenters' email and physical addresses, are available to download from the FCC website.

Karl Bode, a freelance journalist based in Seattle, wrote to the FCC when he found several comments had been left using his identity. Unlike the comments attributed to Margaret Basco and others, the comments left under Bode's name appeared personalized and aimed at undermining his role as a longtime advocate of net neutrality.

Bode complained to the FCC, but in July the agency wrote to him saying that although it "does not condone anyone impersonating someone else's identity," it would not remove the comments.

"Once filed in the FCC's rulemaking record, there are limits to the agency's ability to delete, change, or otherwise remove comments from the record," the letter read.

A spokesperson for Pai told CNN that people whose identities were stolen should submit a comment to the FCC contesting the fraudulent comments.

Responding to the New York Attorney General's request for cooperation last Thursday, the FCC's general counsel, Thomas Johnson Jr., said that the commission did not rely on any of the alleged "corrupted" comments for its draft document that will be voted on on Thursday that would repeal the current net neutrality rules.

Johnson further explained, "the Commission has never burdened commenters with providing identity verification or expended the massive amount of resources necessary to verify commenters' identities."

That's not good enough, Chris Basco thinks.

"Granted this is a large issue and I'm sure they're quite probably overwhelmed by comments, so obviously, a few were going to slip through the cracks," but with millions of fake comments, he said, it appears they fell though "just about every crack you think of."