Most afternoons, Chanda Ranck works out of her home office in a dilapidated trailer parked alongside the mountains in rural Owsley County. The tiny room is modest, with a small desk, a phone, and a headset, but it has a blazingly fast Internet connection -- and that has helped turn Ranck's life around.

After years fighting an opioid addiction and unemployment, that home fiber optic hookup allowed Ranck to get a job as a customer service agent taking calls for U-Haul. The job pays a base rate of $10 an hour, with an extra 25 cents for every truck she rents, and it doesn't require money for gas — an added financial perk since she lives miles from the nearest town.

"You have to drive an hour in some direction to get work," said Ranck, 34. "It was a miracle."

But not everyone in Eastern Kentucky is so lucky. One county over, Ranck works a second job as a counselor for people struggling with addiction. Many of those she helps would benefit from home-based jobs, she said, but they don't have access to fast enough broadband yet. "I see 100 people a week who would love to do this, and can't," Ranck said. "Where they live, it's not accessible."

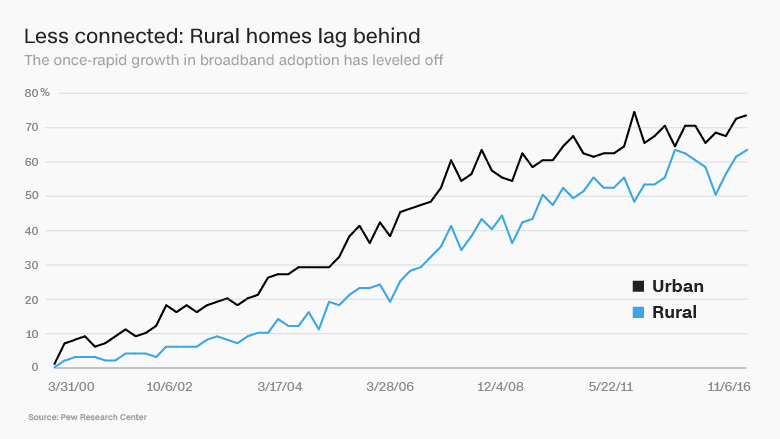

America has seen rapid improvements in broadband availability since the turn of the century. Fueled by both private and public investments, that growth has helped expand the transformative power of the Internet far beyond cities and wealthy suburbs. Household Internet use in rural areas rose from 2% to 61% between 2000 and 2015, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But the momentum has now stalled as public funding has dried up.

President Trump campaigned on the promise of a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, which Internet access advocates had hoped would include another infusion of cash to extend broadband to areas that telecom companies don't find commercially viable. So far, no plan has been proposed.

The slowdown in funding has left stark disparities between rural areas that have gotten wired and those where the job is only half finished.

Take Eastern Kentucky, where a handful of counties received fiber optic connections to every home and business with help from millions of dollars in stimulus funding in 2009 and 2010. Those that didn't, must make do with shaky Internet service over copper wires or phone lines, and they only get pockets of good cell service amid the crinkled mountain landscape.

Related: The end of net neutrality: What it all means

That hasn't stopped Teleworks USA from trying to place hundreds of rural residents in jobs. Since its founding in 2011, the federally-funded job training agency has found home-based work for more than 1,200 Eastern Kentucky residents — including Ranck — and they say the number of remote jobs out there is only growing.

But lack of broadband still stands in the way.

"The thing that limits us placing as many people who need it and want it is the infrastructure in Eastern Kentucky," said Teleworks USA's director, Michael Cornett. "And that's something that's totally out of our control."

Quick progress, big results

Starting in the 1950s, McKee, Kentucky-based Peoples Rural Telephone Cooperative devoted itself to connecting a small corner of Appalachia to the phone system. Along with most of the rest of rural America, it succeeded.

By the 2000s, PRTC was in the Internet business as well. In 2009, Congress allocated $7.2 billion to broadband development in rural areas, and directed the Federal Communications Commission to develop a plan for making high-speed Internet access available everywhere. PRTC got $45 million in a mix of grants and loans to build out fiber to every home and business in the two counties it served.

To Owsley County judge Cale Turner, the broadband access has been a game changer, especially as coal and tobacco jobs disappeared. Teleworks alone has created 137 jobs in the 4,500-person county since opening in 2016.

"The beauty of it is, those jobs are going to keep on coming," Turner said. "You don't have to worry about the factory shutting down. If you built a brick building and hired 130 people, everybody would be gushing."

Related: In this small Kentucky town, people aren't waiting on Trump to fix things

That's only counting the jobs Teleworks has created directly. The county's broadband network also allows high-earning urban professionals like Teresa Duff, a software executive from Dayton, Ohio who has family in Lee and Owsley counties, to move there as well.

"Really the Internet thing was a big deal, because Lee County doesn't have the same capability with broadband," said Duff, sitting at her kitchen table, which looks out on a sweeping pasture for her horses. "So I needed to be here."

There are other beneficial spillover effects. The owner of the Ole Bus Stop Diner in Booneville, Jason Reed, reports more business from teleworkers placing to-go orders and taking their whole families out to eat with their newfound paychecks. Each student at Owsley County schools has super-fast Internet at home, allowing them to keep working when school is closed on snow days and to take online college courses while in high school.

"It's not about new roads," said Owsley County Schools superintendent Tim Bobrowski, whose wife runs an e-commerce business out of their home. "It's the Internet. You can't see that road, but it brings in opportunities that at the time nobody was seeing."

The broadband revolution missed a spot

Fifteen minutes away, in Lee County, an Internet-connected future seems more distant.

The area is currently served only by AT&T, which doesn't usually deliver speeds as high as PRTC's fiber network. (AT&T said it has invested $700 million in building fiber and wireless networks in Kentucky in the last three years, but declined to disclose where those services are available.)

The one coffee shop in downtown Beattyville, the county seat, is full of people using Wi-Fi because they don't have a good Internet connection at their homes.

"We see a lot of draw, just because we do have Internet access," said Jessica Miracle, manager of the Art Factory Coffeehouse. "A lot of the county doesn't."

According to the FCC's latest broadband access report, 39% of rural residents lack fixed broadband service, compared to just 4% of city dwellers. That's down from previous years, but still cuts off a broad swath of the population from learning and job opportunities.

PRTC is working on building out to Lee County now, investing about $600,000 into running fiber to some of the local institutions, like the library and the courthouse. But getting to peoples' homes and further-flung businesses is expensive. While some pots of federal money are still available, they have yet to secure the millions that allowed them to connect the other two counties next door.

"Unless we get a grant there, all the risk is ours," said Keith Gabbard, PRTC's CEO. In that scenario, success depends on the number of people who want to sign up. "If we get 20 homes, then we'll do it, but if it's one or two homes, it's a matter of funding."

Related: 'Child care deserts' are leaving parents with few options

In the meantime, some states have tried to fill in the gaps — some more successfully than others.

In 2015, Kentucky's former governor kicked off a $324 million public-private partnership that was supposed to construct 3,000 miles of fiber optic cable as a "middle mile" to get closer to rural communities. The first ring was scheduled to be operational by this July, but the project is now far behind schedule and over budget, which officials in the new governor's administration attribute to original projections being "unrealistic."

That's left Lee County to do what it can with what it has. The schools, for example, keep their buildings open on snow days to allow kids without home Internet to come do assignments, and make sure everything's possible to do using old-fashioned paper and pencil.

"We are limited somewhat," said Lee County superintendent Jim Evans. "But we try to work through those problems."