If farmers want to know how healthy crops are, perhaps they shouldn't trust their eyes.

Matt Free -- a manager at Evergreen FS, an agriculture company -- learned that lesson this year. His team provides crop protection services such as fertilizers and herbicides to farmers across Illinois.

After a year-long test of a variety of new technologies, Evergreen FS found artificial intelligence could identify trouble, such as fungus growth and water shortages, in corn and soybean crops weeks before the naked eye would ever realize it.

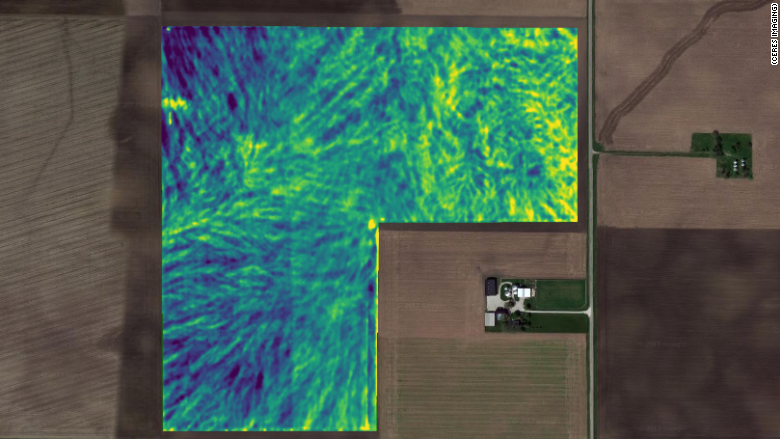

The tech, which comes from startup Ceres Imaging, offers farmers an AI analysis of photos taken from planes flying several thousand feet above fields. Previously, the technology was generally limited to orchards and vineyards.

After images are taken, Ceres provides maps that highlight trouble spots on farms. Free's team visited the marked areas, but couldn't detect any issues with their own eyes.

Two or three weeks later, the artificial intelligence was proven right: problems emerged, including disease.

According to Michael Gore, a Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences professor, artificial intelligence has a bright future in agriculture. It's not a panacea, but he expects it will be commonly used among corn and soybean farmers in five to 10 years.

"With what we can see with our eyes, it may be too late to even treat a crop," Gore said. "If you can see something very early, like a pest, then the farmer can react a lot faster and help prevent productivity loss."

But the technology has limitations. Like all AI systems, it is only as good as the data it's trained on. It cannot perfectly diagnose every field.

The Ceres Imaging tech relies on a sensor that measures light wavelengths that the human eye can't see. These wavelengths are then analyzed to provide a sense of the health of crops.

The cost, which ranges from $6 to $10 an acre depending on the crop, is less expensive than applying some fungicides.

Evergreen FS said it will start offering the tech to corn and soybean farmers during the 2018 growing season.

"This is the wave of the future," Free said. "Farmers have less time to go to every individual field and need tools to make quicker and more effective decisions."

The effort to identify diseases early can make a significant difference in how many bushels a field delivers. It also represents a shift to mass market crops and broadens the opportunities for artificial intelligence to impact agriculture. Corn and soybeans are the leading crops grown in the United States.

Related: Farmers turn to artificial intelligence to grow better crops

Some tomato growers use a network of cameras in greenhouse roofs to monitor plants and identify any issues. Some farmers have tested drones as a way to automatically monitor their fields.

Meanwhile, Ceres Imaging expects to transition from airplanes to drones as regulatory hurdles are removed and the technology improves.