Employers of some of the country's lowest-paid workers are stealing billions from their paychecks -- and federal and state law enforcement agencies have only been able to recover a fraction of those lost wages.

According to the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, government agencies — as well as private lawyers — recovered almost $2 billion in wages that should have been paid to workers in 2015 and 2016.

For the last few years, labor advocates have sought to bring more attention to the issue of "wage theft," which can take many forms: Requiring workers to stay after their shift officially ends, failing to pay overtime or taking deductions that reduce total hourly pay to below the minimum wage.

It's a big problem in low-wage industries like residential construction and warehousing, but the most visible offenders are retail and restaurant chains, which have high turnover and often employ undocumented immigrants who are more vulnerable to intimidation from an employer should they complain.

In recent years, several progressive cities have passed ordinances allowing local law enforcement to police wage theft, and the Department of Labor under the Obama administration hired more investigators to go after problem employers.

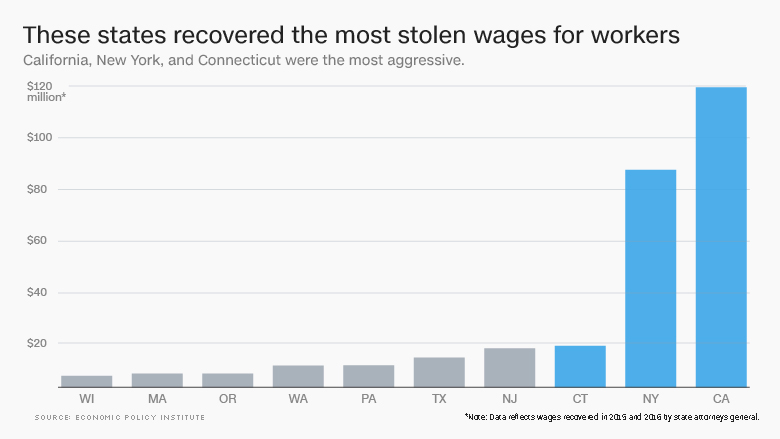

Still, EPI's compilation of state wage theft settlements shows that some states are much more aggressive than others.

California recovered nearly $117 million for workers between 2015 and 2016 — more than a third of the total amount recovered by the 39 states from which EPI received figures. That was followed by New York, which won back $84.6 million.

When adjusted for the size of the workforce, Connecticut comes out in front, recovering $9.66 per capita over those two years. Compare that with last-ranking Indiana, which only got back 19 cents per worker on average.

Related: Trump administration rule could force workers to share tips

Although it's possible that the severity of wage theft varies across states, the EPI researchers found that the amount recovered has more to do with the resources devoted to enforcement and the legal tools available in each state.

California, for example, requires employers to issue each worker a notice of their rights, including the pay rate and who they can call if it's not reflected in their paychecks. The state also hosts a wealth of labor union-aligned nonprofits with the capacity to educate workers about the law and how to file complaints.

In states that don't have strong protections, workers can be very reluctant to report wage theft, especially if the payoff is small and the possibility of retaliation — such as getting demoted or losing one's job — is high. An earlier EPI study based on government survey data found that workers in the 10 most populous states alone likely lose about $8 billion a year in underpaid wages.

Still, state attorneys general accounted for only $317 million out of the nearly $2 billion recovered for workers in 2015 and 2016. The rest of the money came from the federal Department of Labor's $513 million in wage and hour settlements, and $1.2 billion in payouts stemmed from lawsuits, many of them class actions.

Payouts through litigation, in particular, jumped dramatically over the past two years. The value of just the top 10 wage and hour settlements, as compiled by the law firm Seyfarth Shaw, tripled between 2014 and 2016, to $695 million.

Part of that total was driven by a few very large settlements in long-running lawsuits, including $466 million paid in two cases against FedEx for misclassifying drivers as independent contractors, and therefore not paying required overtime. In a statement, FedEx says it settled the case "to remain focused on meeting the needs of our customers."

But according to Seyfarth, the high total was also due to the fact that while recent Supreme Court cases have made it difficult to mount a class action lawsuit in cases of employment discrimination, circuit courts of appeal — especially those in New York and on the West Coast — have continued to welcome the multi-plaintiff wage and hour lawsuits that are more lucrative for lawyers.

Related: Americans see jobs aplenty. Good wages? Not so much

"Prosecution of wage and hour lawsuits is a relatively low cost investment, without significant barriers to entry, and with the prospect of immediate returns as compared to other types of workplace class action litigation," Seyfarth's report reads.

However, that may soon change. In October, the Supreme Court heard National Labor Relations Board vs. Murphy Oil USA, which could uphold employers' right to bar their workers from mounting class action lawsuits, forcing them instead into individual arbitration.

Celine McNicholas, co-author of EPI's report, says that would make it even more difficult for workers to address underpayment of wages at a time when government enforcement isn't up to the task.

"There is rampant wage theft out there, and you're seeing the private bar respond to that," McNicholas says. "If you take away the class mechanism, that private enforcement will be taken away from workers as well."