Long before scores of cities vied for Amazon's second headquarters and the thousands of well-paid tech workers it would attract, local governments began competing for a different part of its business: Fulfillment centers.

The nonprofit Good Jobs First has tabulated that from 2005 to 2016, counties, cities, and states gave up a total of at least $1 billion in tax revenue to attract the massive warehouses where Amazon sorts and ships goods to customers with the hope of creating more jobs and revving up their local economies.

But according to a new study, they may not be getting much of a job boost in return.

Examining job growth in the two years following the opening of 54 fulfillment centers between 2001 and 2015, a pair of economists from the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute found that while warehousing employment increased by about 30%, Amazon's presence generated no net employment gains in the 34 counties where the facilities are located.

Warehouses typically employ between a few hundred and a few thousand people, so the finding could mean one of two things: Either the new jobs are being offset by a decline in other industries, like retail or manufacturing, or the job growth is so small that it doesn't make a meaningful difference

Although the researchers don't answer the question of why Amazon fulfillment centers don't seem to add jobs overall, the authors argue that their conclusions are at least evidence that tax breaks for fulfillment centers don't make sense.

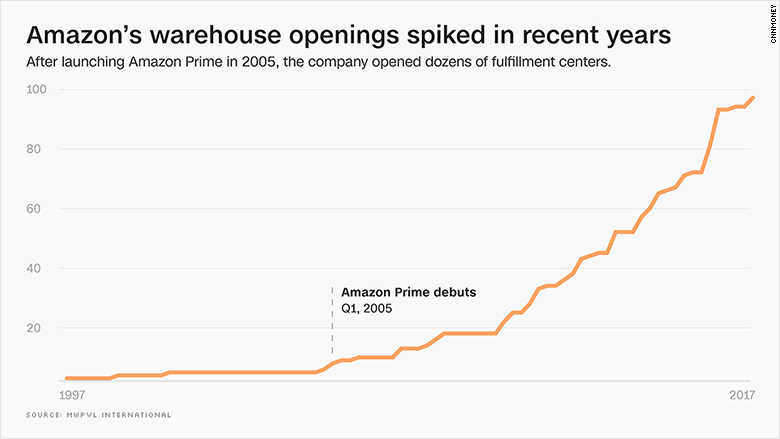

Since the advent of Amazon's Prime subscription service offering free two-day delivery in 2005, fulfillment centers have mushroomed rapidly. Amazon had built 95 such facilities in 2017, according to a private data set obtained by EPI, which omitted a few counties from its analysis because full employment data wasn't available.

Although the warehouses are spread across the country, some states have many more than others — Kentucky and Pennsylvania lead the pack, with 12 and 11, respectively — and a handful of counties strategically placed outside major metropolitan areas have several. Cumberland county, Pennsylvania, for example, became home to four Amazon fulfillment centers between 2010 and 2015, and Amazon is now the county's third largest employer.

Related: What you need to know about Amazon's 20 final cities

In Cumberland County, as with many places, Amazon distribution facilities are one of the only large sources of new jobs available as manufacturing declines. But Mark Price, a labor economist with the nonprofit Keystone Research Center who lives in the county seat of Carlisle, said the warehouses are not creating the ancillary jobs that manufacturing does. A Toyota plant, for example, would also attract smaller factories that supply auto parts.

"Just because Carlisle got an Amazon fulfillment center, it's not generating all sorts of new knock-on employment growth and opportunity," Price said. "If you're going to go out of your way to get one of these things, that's probably not a good investment if you don't have those Toyota effects."

Amazon, which reviewed EPI's study, argues that looking just at the period between 2001 and 2015 is "misleading as it includes the time in which communities struggled during the recession and when Amazon was not building out its network of fulfillment centers as it is today."

In 2016 alone, using an economic impact model published by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Amazon estimates that its overall investments in the U.S. contributed $45 billion to the U.S. economy and added $25 billion in wages. According to the same model, Amazon's 200,000 U.S. employees led to the creation of 200,000 additional non-Amazon jobs, ranging from construction to healthcare positions.

Of course, many localities very much appreciate Amazon's presence. John Snider is the director of the Economic Development Authority of Bullitt County, Kentucky, which has four distribution centers just south of Louisville that employ about 4,000 people.

"They've been a good corporate citizen," Snider said, citing the competitive wages and benefits Amazon pays and its support for local schools. Amazon was attracted to Bullitt County by the local airport hub, and neither asked for nor received any incentives from local government, Snider said.

Related: Big tech tried to boost Washington clout in first year

Michael Mandel, an economist at the Progressive Policy Institute think tank, has found that the e-commerce industry creates more jobs than those that have disappeared from the brick-and-mortar retail sector. He criticized the EPI study for omitting the small counties with incomplete employment data, since they would likely show a larger impact from new warehouses and said it's impossible for the Amazon facilities not to have an impact. (PPI receives funding from Amazon.)

"The premise is absurd," Mandel said. "Putting in a big employment operation into a place that has had trouble finding jobs has a positive economic effect."

In response, the EPI study's co-author Ben Zipperer ran the numbers including all the counties, and said the results didn't change. And while economic impact formulas will always show growth in indirect employment, there's no guarantee those jobs actually appear.

"The point of our study was to actually see if that's happening in the data, not to simply assume it to be the case by resorting to a model," Zipperer said.