Thousands of the country's smallest banks and dozens of regional lenders may finally get the relief they've been aching for.

For the past eight years, banks like State Street, BB&T and SunTrust have fought tougher regulations crafted by Congress in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Banks argue those rules have hurt their ability to lend and help stimulate the economy.

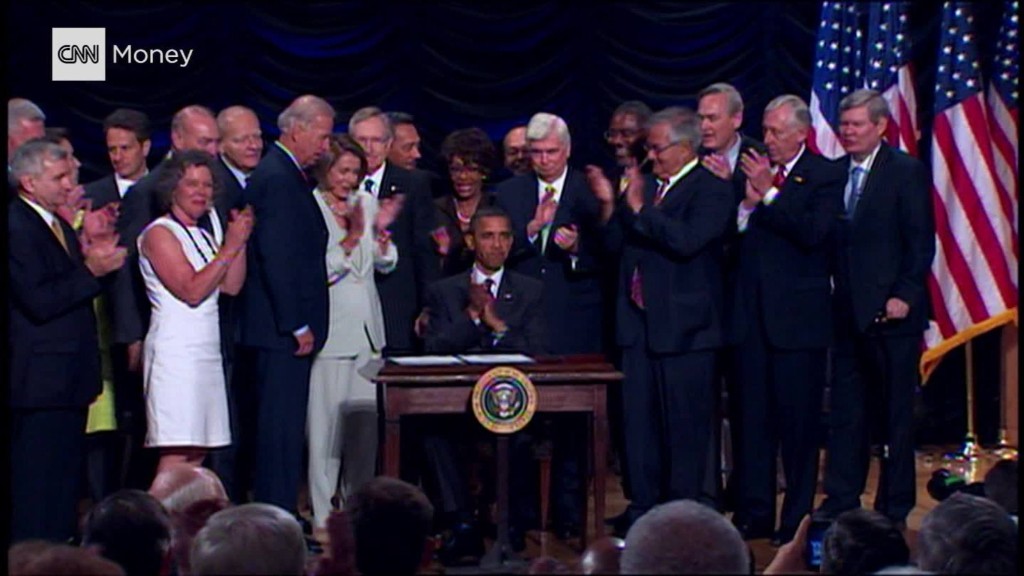

Now those lenders are inching closer to a respite with the most significant changes ever prescribed to the 2010 Dodd-Frank regulatory reform law.

"Main Street businesses and lenders tell me that they need some regulatory relief if we want jobs in rural America," Democratic Senator Jon Tester of Montana said during a hearing to vet the bill in November. "These folks are not wearing slick suits in downtown New York or Boston. They are farmers, they are small business owners, they are first-time homebuyers."

Backers of the plan argue that smaller financial institutions shouldn't have to face the same set of strict rules as behemoth Wall Street banks that could endanger the whole financial system if they go under. Top bank regulators all agree fixes should be made for community banks.

Related: Fed official appointed by Trump lays out plan for easing bank rules

The fixes, which have support from both parties in Congress, would raise the threshold at which banks are considered "too big to fail." That trigger, now set at $50 billion in assets, would rise to $250 billion.

That means more than two dozen midsize U.S. banks would be shielded from some Federal Reserve oversight.

They would no longer have to hold as much capital to cover losses on their balance sheets. They would not be required to have plans in place to be safely dismantled if they failed. And they would have to take the Fed's bank health test only periodically, not once a year.

The American operations of big foreign banks, like Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and Banco Santander, would also be exempt.

Progressive Democrats say the bill goes too far in rolling back necessary financial rules.

"This is a question of whose side are we on," Senator Sherrod Brown, the top Democrat on the Senate Banking Committee, told CNNMoney in a statement. "It's despicable for Congress to put Wall Street and foreign megabanks ahead of working families, especially at a time when banks are making record profits and benefiting from a massive tax giveaway."

Related: Senators block proposed fixes to bill rolling back Dodd-Frank

The bill was crafted by Republican Senator Mike Crapo of Idaho, the chairman of the banking committee. It is backed by 12 mostly moderate Democrats and 12 Republicans.

Majority Leader Senator Mitch McConnell is expected to bring the bill to the Senate floor as early as the last week of February. That timing could slip to as late as mid-March as senators finish their 2017 homework.

Although the bill would be meaningful, it is narrowly focused. It is not nearly as sweeping as a House GOP-backed plan that would gut much of the 2010 law. Nor does it go as far as progressive Democrats would like in strengthening consumer protections.

Republicans want to dismantle the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, while Democrats want better protections for student loan borrowers and stronger tools for consumers to control their credit reports.

But it is the final deal that Crapo brokered after several years of tough bipartisan negotiations.

What comes next will be a delicate negotiation to get a bipartisan bill across the finish line — an unusual feat in Congress these days.

Related: Trump vows to punish Wells Fargo for 'bad acts'

Including Democratic support, the bill already has the 60 votes needed to pass the Senate. Republican leaders now have the added challenge of ensuring any changes to the bill won't sacrifice a single vote.

"The margin of error is pretty small," said Ian Katz, an analyst with Capital Alpha Partners.

No significant changes are expected, but protections could be strengthened for consumers against credit agencies like Equifax, and provisions could be added to help businesses get access to capital, according to those familiar with the process.

Related: Gary Cohn fears this is how the next crisis will happen

The biggest hurdle will be reconciling the Senate's vision with demands by House Republican lawmakers, who would prefer to undo the Obama-era law altogether.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said earlier this month that he was "cautiously optimistic" that both Crapo and House Financial Services Chairman Jeb Hensarling would be able to sign off on a bill.

It remains unclear how much influence Hensarling will want in finalizing the legislation, a hallmark of his legacy before he retires at the end of this year.

He faces at least two immediate constraints. With no plans to run for re-election, Hensarling has limited time to hold up the process and make big changes to the Senate bill. Second, he has to be careful that any changes to the bill won't alienate Democratic support and torpedo the bill.

Last summer, on a party-line vote, the House passed the Financial Choice Act, which would undo much of the 2010 regulations and give the president the power to fire the director of the consumer bureau.

Since then, Hensarling, a Texas Republican, has worked to advance several bills with strong bipartisan support that would give consumers greater access to credit and cut red tape on businesses and banks.

Related: Too-big-to-fail banks keep getting bigger

Analysts say that legislative strategy could give Hensarling a stronger hand if he wants to change the Senate bill.

But Isaac Boltansky, director of policy research at Compass Point Research, said even with the passage of standalone bipartisan bills, the odds are increasing that House lawmakers will have to accept the Senate bill as the clock runs out.

"The House is going to be caught between a rock and a hard place," Boltansky said.