The men who run the biggest companies in tech right now -- they are, still, almost entirely men -- are not, for the most part, shy or modest.

Elon Musk sends things into space and promises to use a bunch of tubes to change transportation as we know it. Jeff Bezos seemingly hasn't met a retail-related sector he doesn't want to dominate. Mark Zuckerberg goes on nationwide listening tours and sparks speculation of a presidential run.

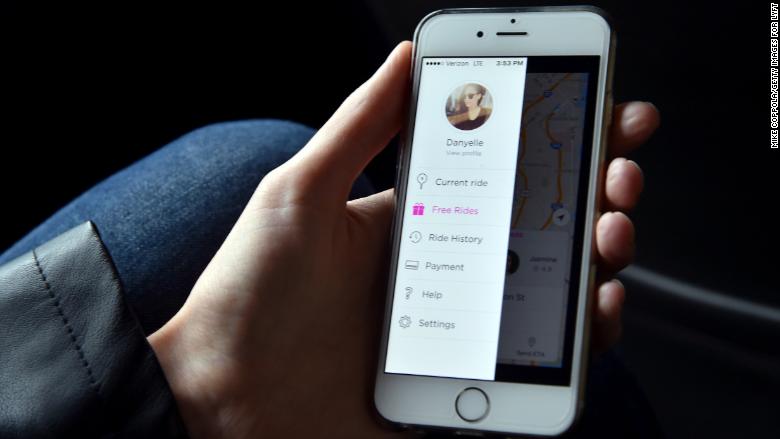

Then there's Logan Green, the 34-year-old co-founder and CEO of Lyft, now valued at $11.5 billion. He still carpools to work in his Nissan.

In an age of celebrity CEOs and outsized egos, Green stands out for the degree to which he doesn't stand out. He's content to let his co-founder be the public face, the one who gets famous. He's had at least one new employee who had to be told gently by a colleague that they should try to remember to give him room to speak in meetings, because he won't cut people off.

Sign up for the PACIFIC newsletter and get daily updates on the stories you need to know

"When some people first meet Logan they say, 'I don't fully understand Logan yet. I don't know what he's thinking,'" Green's Lyft co-founder John Zimmer told CNN recently. "It's just because he's an introvert and he's processing. He's trying to come up with the clearest, best answer that he can develop."

That's exactly what Green has been trying to do with transportation ever since he was in high school.

"I [used to] sit in traffic going to school and my job and see one person in every car, thinking how frustrating this is," he told CNN. "Los Angeles is a classic example of a city that's designed around cars instead of around people. It creates this self-fulfilling cycle where you have to own a car to get around so everyone owns one, and everyone's stuck in the same mess."

After high school graduation, Green enrolled at the University of California-Santa Barbara along with his girlfriend, Eva, who is now his wife. He left his car at home to experiment with transportation. When Eva transferred schools, Green endured three years of weekend commutes on Greyhound to visit her in Los Angeles, three hours away.

"The point was to feel the pain," Green said. "When an axle, or whatever, fell out of the bus in the middle of an intersection in Oxnard, California, and I was sitting there for hours, it's moments of pain like that that really made me think, 'How can we do this better?'"

Underneath Green's pleasant, modest exterior lies a ferocious intensity and an obsession with transportation that's gotten him this far. Now, as his rival Uber is in recovery mode, car ownership rates may have hit a peak, and self-driving cars loom, the question is whether Green can keep his company growing.

If he does it, he'll do it with Zimmer, with whom he drives to work, and who he sits next to in Lyft's San Francisco headquarters.

"It's 100% a bromance," said Amy Fox, one of the first employees at Zimride, the startup that morphed into Lyft, where she now leads business development and strategic partnerships. "I've joked with them, 'Do your wives know about John or Logan?'"

With a small nod, they know exactly what each other are thinking, according to Green. Getting on the same page can require just a couple words.

"I've been on a lot of boards," said Valerie Jarrett, the former advisor to President Obama who joined Lyft's board in 2017. "This is the first one where I've seen the CEO work quite so closely in such a deep partnership like the one Logan has forged with John."

But it wasn't always easy. Green recalls a lot of painful arguments in their first years working together.

"To John's credit, I'm one to sort of argue but not insist that we get to the breakthrough. John loves communicating more. He kind of forced it. 'Ah, O.K., this is painful, we're going back and arguing some more,'" Green said. "Now we just have this trust where it's really easy to argue about the issue."

Over the years, the media has labeled the Lyft founders the "nice guys" of ridesharing, arguably not suited to take on Uber. Green disagrees.

"We're like cutthroat missionaries," Green said. "I think people see the missionary aspect, or see that we care about taking care of people, and assume it means we'll be soft when it comes to competing."

Related: Lyft tries to fix LA's traffic

Many observers thought ridesharing would play out as a winner-take-all market, and portrayed Uber and Lyft as locked in a steel-cage death match.

"People talk themselves into these narratives and use these anecdotes to come to conclusions that are totally off base and totally false," said Green, who recalled how Lyft identified the scale needed to deliver reliable pick-up times for customers and set a fundraising target to get there. "That completely neutralized the kind of experience advantage Uber had in the early days," he said.

Green also credits surviving battle with Uber to having endured the early, anxiety-filled days of Zimride, where they'd hustle to close deals, and try to get paid up front so they could make payroll.

"For years I lived in this world where the cliff was always three months away. I mentally got very comfortable with living in the world of immense risk and immense threats. So competing against Uber, at their peak they had 30 times the cash we did, was just another fact of life," Green said. "We were doing a hell of a lot better as a company and in 1,000 times better position than just a few years before."

Both companies continue to grow today. But Uber is far larger than Lyft, giving 10 million rides a day globally. Lyft, which only operates in the U.S. and Toronto, gives more than one million rides a day. Uber has raised more money from investors than any U.S. startup.

And because Uber has worked to clean up its act, Lyft risks losing its edge as a more driver-friendly company, according to Harry Campbell, editor of The RideShare Guy, a blog devoted to Uber and Lyft drivers.

"Uber had probably the worst year of PR ever, and Lyft made incremental gains," Campbell added. "If they couldn't surpass Uber last year, I don't know what could happen that would allow them to do so."

Melissa A. Schilling, a New York University business professor and author of "Quirky: The Remarkable Story of the Traits, Foibles, and Genius of Breakthrough Innovators Who Changed the World," believes the challenge for Green is finding the next innovation.

"Serial breakthrough innovators have idealism. Green has that going for him," Schilling said. "But is he going to have another innovation and another innovation and another innovation? I don't know because we haven't seen it yet."

Green appears aware of that challenge.

"Every time we plan what we're doing next quarter, every time we plan out the next year, it's going to look like a different company. The number of elements that change every quarter, every year it's mind boggling how fast it's moving," he said.

The next big shift is self-driving vehicles. As early as 2012, he wanted to pitch investors on self-driving cars as part of Lyft's future.

"We got feedback that we would be laughed out of the room," Green recalled. "'Don't put it in, you guys sound crazy. You're going to lose credibility.'"

In the future, Green envisions a few big networks of self-driving cars, along the lines of AT&T and Verizon. In his vision, Lyft would effectively park, service, clean, fuel and insure your ride.

For example, a shared commuting vehicle could feature WiFi, spots for laptops, and a quiet atmosphere. A weekend-getaway vehicle may have a leather couch and a place to store drinks. Another car with a large TV screen could prompt a rider to watch their favorite show.

It's a future where Green would never have to face the one thing that Fox, his longtime colleague, has ever seen make him truly angry.

In Zimride's early days, Fox recalled recently, Green left to buy lunch for the staff. He returned livid, waving a parking ticket in the air.

"All of us were like, 'Oh my god," Fox said. "'I've never seen this side of Logan. This is great.'"