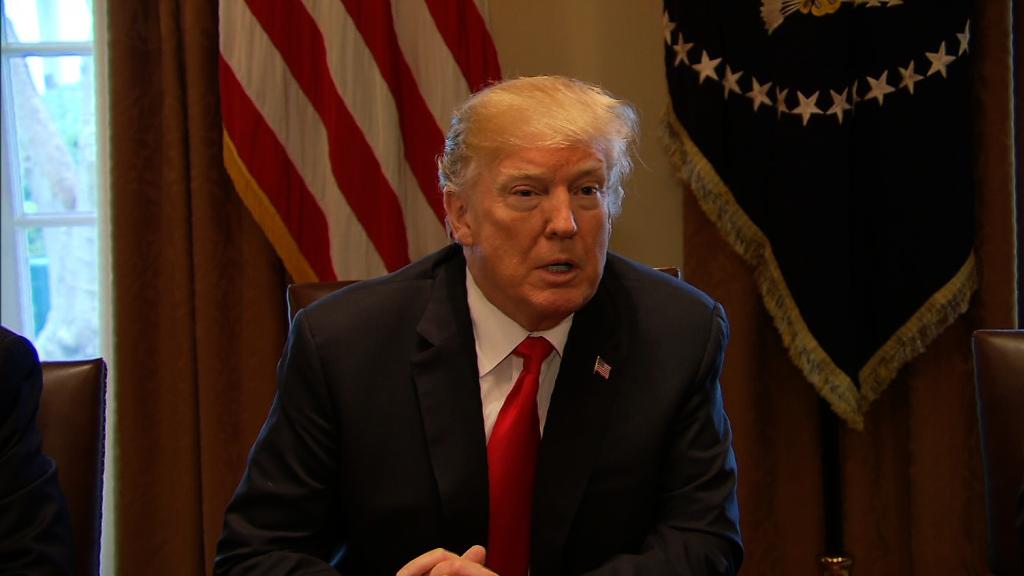

Big business has sent distress signals since President Trump decided to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum.

But Tim Timken couldn't be happier. The CEO of TimkenSteel was in the room at the White House last week when Trump made the surprise announcement.

"We view it as a very positive thing," says Timken, who represents the fifth generation in the 101-year-old business. "I'm confident by the end of the week we're going to end up with something we're going to be very supportive of."

Trump plans to impose a 25% tariff on foreign steel and a 10% tariff on foreign aluminum. It's unclear whether certain countries will be exempt.

TimkenSteel is a publicly traded company, and the family has a controlling stake. It employs about 2,800 workers. Average pay is about $90,000 a year, including benefits, Timken says.

TimkenSteel's customers include General Motors (GM), Ford (F), Honda (HMC), Halliburton (HAL) and Caterpillar (CAT), among others.

Related: Steel tariff could cost Ford and GM $1 billion each

It's been a tough few years for the company. Between 2015 and 2017, TimkenSteel laid off 380 employees because steel prices fell too low. It has hired back about 175 workers in the last several months.

China has long been accused of flooding the global market with cheap steel at prices that are unfairly low by US standards. Previous US administrations have imposed a litany of trade barriers on Chinese steel, which only accounts for about 2% of US steel imports. But China continues to sell en masse elsewhere, which suppresses global prices.

Trump's measure would also target US allies such as Canada, Mexico, South Korea and Brazil, all of which import more steel to the United States than China.

All those countries have warned they will retaliate against American exports. Even one of TimkenSteel's competitors with US operations, ArcelorMittal, has asked Trump to give Canada an exemption because it has a factory there too.

Related: Larry Summers: Trump's tariffs are 'crazy, dumb'

Timken says people need to relax, and he says no countries should be exempt, but that there's a fair case to made for some exemptions for certain products.

"There's a lot of talk about trade wars and retaliation. History would say those fears are mostly overblown," Timken says.

He points out that President George W. Bush imposed a 30% tariff on imported steel in 2002. Timken argues that the Bush tariff didn't cause widespread economic damage or trigger a trade war, with other countries imposing tariffs on US goods.

That's broadly true: Unemployment barely changed, hovering around 6%, and the economy continued to grow.

Related: A Trump trade war would hit red states hard

However, a 2003 report from the U.S. International Trade Commission found that the tariffs caused headaches for some businesses.

Nearly half of companies told the ITC they had trouble getting the quantity or quality of steel they needed. Employment in steel-consuming industries, such as car companies, fell or stayed flat. About a third of these companies reported production delays.

Corporations' profits rose, but companies cut back on investing in their operations — for example, buying new equipment — as they faced less foreign competition. Nearly 20% of companies said they passed higher prices on to consumers.

The World Trade Organization ruled the Bush steel tariffs illegal in November 2003. A month later, Bush removed them.

Timken says steel makers need more help today in a world where foreign leaders are dictating steel prices.

"Given a leveling playing field, I can go toe to toe with anybody in the entire world," Timken says. "My problem is that I'm competing against governments right now."