The slow but steady recovery from the Great Recession just hit a milestone: It's tied for the second-longest economic expansion in American history.

The recession ended in June 2009, which means the recovery is 106 months old through April of this year. That matches the expansion from 1961 to 1969, an era of big government spending under President John F. Kennedy and then President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society.

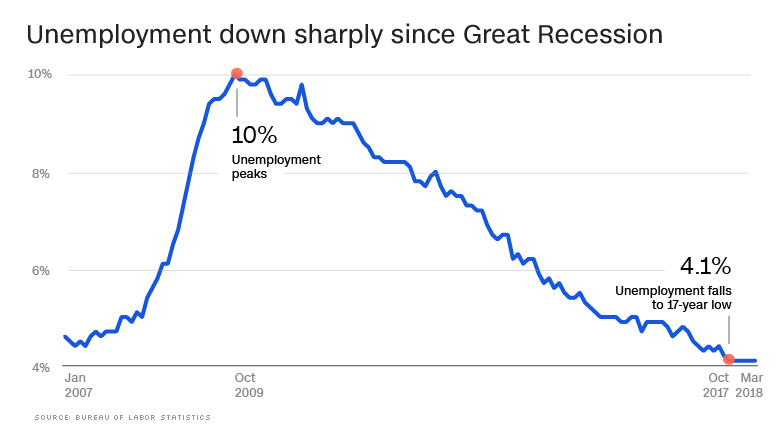

Unlike the breathtaking growth of the 1960s, the current expansion won't set any records for speed. It took far longer than many hoped for unemployment to get back to healthy levels. Wages have only recently begun to accelerate meaningfully.

Yet the very fact that the economy didn't roar back to life from the financial crisis extended the life of the recovery. The slow speed prevented it from overheating.

"The silver lining is this very long economic expansion," said Moody's Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi. "We didn't experience the same boom-to-bust cycle that we had in the past."

Low and slow

Scarred by the 2008 meltdown, businesses and individuals were reluctant to take on risks during the early years of the recovery. Many were still working off the debt from the last boom.

"Everyone ran for the proverbial economic bunker, and it was hard to coax them back out," Zandi said. "People were shell-shocked."

The absence of explosive growth and problematic inflation meant the Federal Reserve didn't have to step in with aggressive rate hikes aimed at cooling the economy down. Low rates and steady growth allowed the stock market to quadruple from its March 2009 low.

Related: 58% of investors say 2018 is the peak for stocks

Economists don't see a recession on the near horizon, meaning the recovery has a real shot at staying alive until July 2019, when it would surpass the 1991-2001 boom as the longest on record. That expansion lasted exactly 10 years and was powered by the rise of the internet.

"Absent a shock like a trade war, we're likely to become the longest expansion," said PNC chief economist Gus Faucher.

He noted that because growth has been mediocre, few of the boom-time excesses have built up in housing markets, corporate balance sheets or household credit card statements.

"This is an economy that has been growing steadily at an OK, not fantastic pace. Things are well balanced," Faucher said.

Just 13% of global fund managers polled by Bank of America Merrill Lynch in early April think a recession is likely in the near term.

Unemployment has steadily dropped to 4.1%, the lowest since 2000. That's down dramatically from a peak of 10% in 2009. Economists predict it could keep dropping, perhaps into the mid-3% range. That hasn't happened since 1969.

Distant threat

One reason growth is predicted to continue for now: Washington is borrowing heavily to spend more and tax less.

Republicans passed tax cuts for businesses and individuals late last year. Then lawmakers reached a bipartisan agreement this year to ramp up spending. That recipe, normally reserved for downturns, typically stimulates growth.

All that deficit-financed aid from Washington is juicing growth now, but it may also speed the demise of the recovery.

"It's laying the foundation for the next recession," Zandi said.

He predicted that the tax cuts and government spending will accelerate growth, increase inflation and eventually force the Fed to slam the brakes on the economy.

"By mid-2020, we will be most vulnerable to the next recession," Zandi said, pointing to the fading impact of government spending and tax cuts.

Related: My road back from the Great Recession

Hedge fund billionaire Ray Dalio recently estimated there's a 70% chance of a recession before the November 2020 presidential election.

Even if a recession isn't imminent, Wall Street is starting to think about the end of the business cycle.

Fifty-eight percent of the money managers polled by Bank of America think the stock market has already peaked or will later this year.

Morgan Stanley chief US equity strategist Michael Wilson warned in a report on Sunday that "2018 will mark an important cyclical top" for US and global stocks, led by a "deterioration" in the credit markets.

Like other economists, Zandi questioned the timing of the tax law and spending hikes given the health of the economy.

"It's almost like you read the economic textbook and did the opposite of what it said to do," Zandi said. "It's a real experiment — and in my view, it won't end up well."