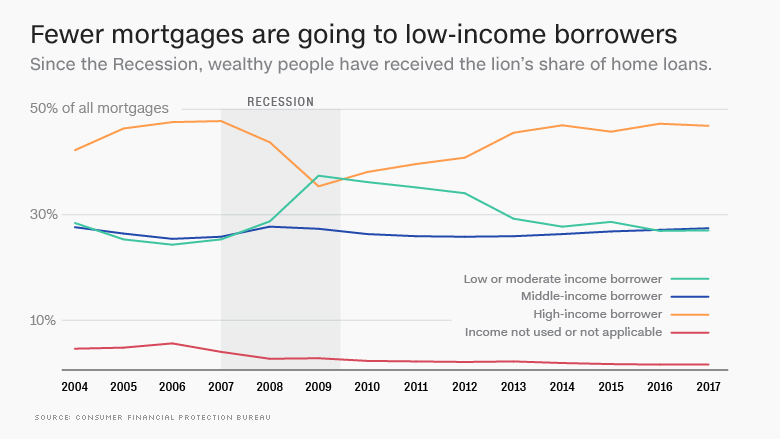

Banks have been walking away from low-income homebuyers seeking loans, and that has affordable housing advocates worried.

Newly-released federal data on mortgage lending from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau shows people with low- and moderate-incomes made up only 26.3% of borrowers in 2017, down from 36.6% in 2009.

In part, that's due to federal rules that sought to crack down on the subprime lending tactics that helped bring on the financial crisis. Also, skyrocketing housing costs have locked many people of modest means out of the market.

But the data reveals another profound shift. Big banks are moving away from mortgage lending entirely, while independent mortgage companies — or "non-banks" — pick up the slack.

"Non-bank" is a catchall term for financial institutions that don't take deposits. Non-bank mortgage lenders just do mortgage lending, for example. So in a time of low interest rates and higher regulatory costs, traditional banks have the option of moving into more profitable ventures, like credit cards.

"Profit margins on lending have come down quite a bit," says Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association, which represents both banks and non-banks. "So a number of banks have de-emphasized their mortgage lending, because there are other business lines they can focus on."

Related: This Texas military town has nearly closed the black-white homeownership gap

Non-banks, meanwhile, have doubled down on volume — particularly through refinances — and now originate 56% of all home loans, according to the CFPB data.

Now, the biggest mortgage lender in the country isn't a bank at all — it's Quicken Loans, which originated 27% more loans in 2017 than its nearest competitor, Wells Fargo.

And as banks have moved away from the mortgage business, they've fled even more quickly from lower-income black and Hispanic buyers, who often apply through the more forgiving Federal Housing Administration loan programs. Only 15% of the new mortgage borrowers at the nations' three largest banks were low-income in 2017, compared to 29% for the three largest non-banks.

Large banks have blamed their departure from FHA lending on litigation brought against them by the Department of Justice under the False Claims Act, which led to big penalties for Wells Fargo (WFC) and JPMorgan Chase (JPM) for approving loans that had not been certified as eligible for FHA insurance.

But advocates for low-income homebuyers charge that banks are simply retreating to a more lucrative segment of the market.

"Frankly it's kind of disturbing to me," says Jesse Van Tol, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, an umbrella group of affordable housing organizations. "I think you see a number of institutions post-crisis reorienting their bank to a more urban clientele, a more metropolitan clientele."

Related: 10 years after the financial crisis, have we learned anything?

That's a problem, Van Tol says, because non-banks are not covered by the Community Reinvestment Act, which requires depository institutions to do a certain amount of their investing in lower-income communities in the cities where they're based.

"We think every lending institution has an obligation to lend to people of modest means," Van Tol says. "It's not good enough if some people are doing it and others are not."

In addition, economists have raised concerns about the large volume of lending by non-banks. Many of these firms are relatively new and non-public, making it more difficult to assess their level of risk and their capacity to absorb losses if the housing market were to turn sour.