Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes was once lauded as the youngest self-made female billionaire. But her net worth was revised down to nothing after a journalist started digging into the technology behind her blood testing startup.

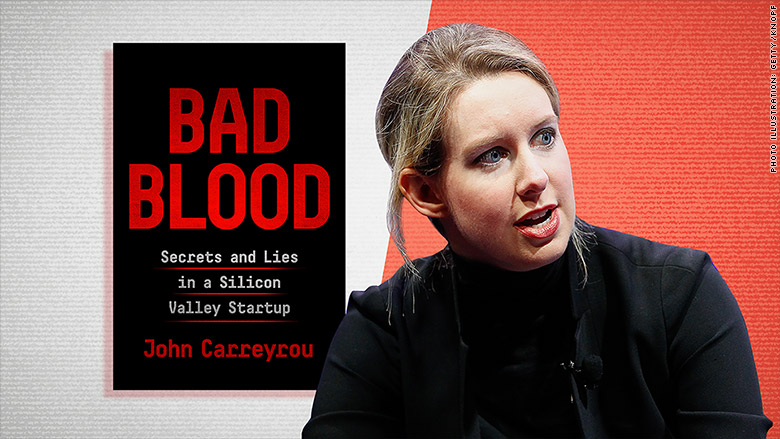

In a new book out Monday, that journalist -- Wall Street Journal investigative reporter John Carreyrou -- sheds light on what went on behind the scenes of the disgraced company.

The book, "Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup," focuses on understanding the culture at Theranos and the tyrannic leadership that steered the startup to its one-time valuation of $9 billion.

Theranos aimed to create cheaper, more efficient alternatives to traditional blood tests using its proprietary technology. But after Carreyrou, a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter, called into question its technology and testing methods in 2015, the company voided two years of blood tests. In May 2018, the SEC charged Theranos with "massive fraud" involving more than $700 million.

The company remains the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation by the Department of Justice.

Following interviews with more than 150 people, including 60 former Theranos employees, Carreyrou paints the picture of what it was like working for Holmes. She was said to have unrealistic expectations, according to Carreyrou, when it came to the startup's blood testing technology and its workers, requiring engineers to work around the clock to speed up development.

"This was an incredibly ambitious woman. She wanted to be the second coming of Steve Jobs. It was an 'ends justify the means' situation. Perhaps she thought [Bill] Gates and Jobs faked it until they made it so why not her too?" Carreyrou told CNNMoney.

Related: Elizabeth Holmes surrounded Theranos with powerful people

After dropping out of Stanford University in 2003, Holmes started Theranos at age 19. She was known for wearing black turtlenecks, a nod to Jobs, and for her ability to attract a who's who of powerful investors and board members. Her squad included two billionaire executives, a top Silicon Valley venture capitalist, and a member of President Donald Trump's cabinet.

Holmes ignored warning signs from employees who raised red flags about the technology's effectiveness prior to introducing it to patients. Holmes expected complicity in elaborate lies, such as staging a fake laboratory to impress Vice President Joe Biden. Those who pushed back or tried to level with her were typically asked to leave the company.

"There's no question in mind that she knew there was a risk that she was putting patients in harm's way," Careyrou said. "The problem was Elizabeth channeled the Silicon Valley culture and way of operating for what was not a traditional tech business -- it was a medical technology business."

According to Carreyrou, employees constantly felt like they were under surveillance. Holmes' administrative assistants connected with Theranos employees on Facebook to report back what others were posting.

"Elizabeth demanded absolute loyalty from her employees and if she sensed that she no longer had it from someone, she could turn on them in a flash," said Carreyrou.

Related: Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes charged with massive fraud

In the book, he writes that firing someone often meant building a dossier on the person to "use for leverage."

"Bad Blood" also examines the role and power exuded by Theranos' former COO Ramesh "Sunny" Balwani. Balwani is an elusive character. A Google search on the executive turns up few results.

Twenty years her senior, Balwani was Holmes' closest confident; the two also had a romantic relationship that was concealed from her board. Balwani is said to have "spawned a culture of fear with his intimidating behavior," Carreyrou writes. When he let employees go, employees would say, "Sunny disappeared him."

Carreyrou wrote Balwani treated employees as his "minions." Dozens of them were Indian citizens on H-1B visas, a popular work visa used in the tech industry to employ highly-skilled foreign workers. Because H-1B visas are tied to an employer, this kept workers on these visas particularly afraid of speaking up. "It was akin to indentured servitude," Carreyrou wrote.

Efforts to maintain secrecy at the company ran deep, he said. Employees -- and anyone who entered Theranos' office -- were required to sign non-disclosure agreements. "We can change people in and out. The company is all that matters," one engineer featured in the book recalls Holmes saying.

Carreyrou said Holmes has "steadfastly refused" to do an interview with him for years. They have never met.

His first expose on Theranos ran in the Wall Street Journal in October 2015, and his coverage is responsible for cracking open and exposing the startup.

"I have very good reason to believe that criminal indictments of Holmes and Balwani are not far away," Carreyrou said.