When she retired from her job as a legal secretary for the federal government at age 62, Linda Spencer thought retirement would be a blast.

Then the Great Recession blew a hole in her savings, and free time wasn't much fun without cash to travel and buy the nice clothes she'd gotten a taste for while working at Saks Fifth Avenue decades earlier.

"I had nothing to do and I got bored and I needed money," says Spencer, 68, who laughs loudly and wears red lipstick.

Jobs were scarce when she went out looking a couple of years ago, and so she found the federally-funded Senior Community Service Employment Program, which helps low-income seniors find employment in Northern Virginia. It pays minimum wage, or $7.25 an hour, for her to do administrative work while she learns computer skills and looks for other jobs — which she now wants for more than just the financial reasons.

"It makes you feel that you're viable, that you're important, that you can contribute something to society, that you matter," says Spencer, who lives alone and doesn't have kids.

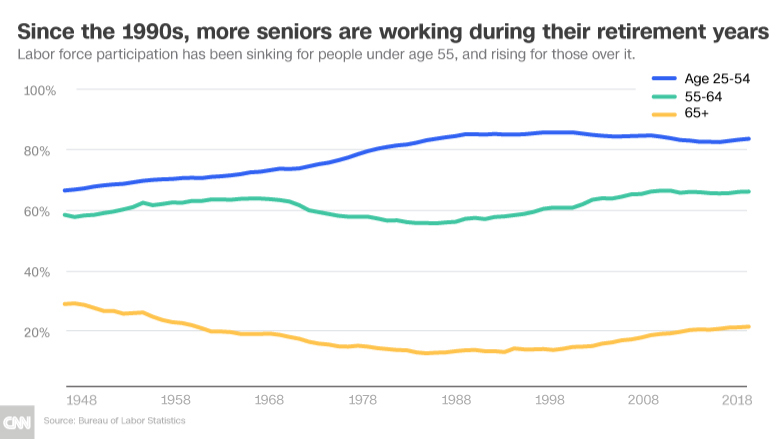

That's an increasingly common sentiment among America's seniors. And it's a good thing, too, because getting more people to work later in life could help blunt the impact of the graying population on the nation's finances, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Baby boomers are reaching retirement age rapidly, and the generations to follow are thinning as the American birth rate sinks ever lower. In March, the Census Bureau reported that by 2035, there will be more Americans over age 65 than there are children under age 18. Not only that, but fewer people in their prime have been working in recent years — which is in part due to the opioid epidemic, mass incarceration, and unaffordable child care that forces many parents to stay home.

Related: The opioid crisis is draining America's workforce

That means not only will there be fewer working-age people paying into programs like Social Security and Medicare that support retirees, but there will be fewer health care and home care workers to help meet their physical and mental needs.

"That's the big challenge going forward," says Keith Hall, director of the Congressional Budget Office, pointing to a chart of projected gross domestic product during a recent presentation in Washington D.C.

So far, older folks seem to be doing their best to bolster America's flagging workforce. Whether they'll be able to continue, however, depends on whether employers themselves will be able to adjust.

Grandparents to the rescue

Seniors are mostly working longer because they need the money. Hikes in Social Security's retirement age, a sinking savings rate, mounting personal debt and a shift away from employer-provided pensions have made it harder than it was in the 1960s and 70s to retire.

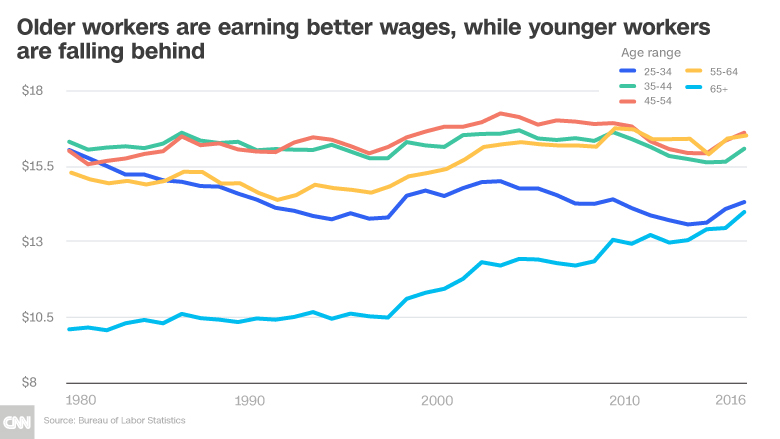

As a result of putting in more hours and earning higher wages older people have seen their incomes rise while wages have stagnated for those who are younger — likely because today's over-60 population is much more educated than previous generations. According to an analysis by the Census Bureau, workers over age 65 saw their monthly earnings increase 80% between 1994 and 2015 when adjusted for inflation, compared to 32% for workers between ages 35 and 54.

Meanwhile, expenses for everything from housing to health care are going up — especially for renters like Spencer. Her studio apartment in Alexandria, Virginia, with no dishwasher and a Murphy bed cost $500 a month when she moved in 19 years ago. Today, it's $1,300 per month, not including utilities.

Luckily, workers are staying healthier and no longer feel that the traditional retirement age is an expiration date. With manufacturing jobs giving way to less physical service and desk jobs, age is less of a barrier to continued employment.

"I think it's hard to walk away from using your mind and being engaged every day, and problem solving, looking for new ways of doing things," says Nancy Peterson, who runs a job website that caters to older workers called Workforce50. "When work dwindles to nothing, it's noticeable."

Related: Will your expenses stay the same in retirement?

That doesn't mean older folks want to keep on working the same way they have their whole lives.

Most prefer part-time jobs, Peterson says, to leave room for activities like volunteering or spending time with grandchildren. Those opportunities abound in low-wage jobs, some of which employers cut down to less than 32 hours a week in order to avoid having to provide health care under the Affordable Care Act.

Kristi Sargent, who manages the employment program that Spencer works with, says she has no trouble finding seniors part-time positions as security guards, pharmacy technicians and low-tech database managers.

"I'm printing out job orders left and right, all day long, sending them to my participants," Sargent says. "If you want a job, you're going to find a job right now."

Older workers are in particularly high demand for positions serving a fast-growing consumer category: People just a few years older than they are in need of health care services.

Elizabeth Chavez, who runs a home care service with North Shore Community Action Programs in Peabody, Massachusetts, has been hiring as many retirement age workers as she can find, since senior clients often relate better to companions who also have gray hair.

And plus, Chavez has found that older people don't hop from agency to agency as much as Millennials, which reduces costs associated with turnover.

"It's a more stable workforce," she says. "It really is a forgotten market that we need to tap into if we want to be successful."

Changing mindsets

The workplace can be a little less friendly for older people in higher-powered professions who just want to cut back their hours.

Business careers usually end with a retirement party, leaving workers wondering what to do next. It can be difficult to find another job, since many employers are still focused on cultivating younger workers who they think might work harder or stick around longer (neither of which is necessarily true).

"I've applied online, and people have called me up, and they say 'when did you graduate from high school?'" says Spencer. "And then they hear that, they go 'click,'" she says, as if hanging up a phone.

She's not imagining things. Research from economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that people over age 60 get fewer callbacks than people in their 30s and 40s.

"I think it's still kind of a Catch-22, where if there's an older person in a really key position, employers are more interested in 'How do I convince that person to stay longer?,'" says Cheryl Paullin, vice president for research at the Human Resources Research Organization. "But once a worker does leave, employers still aren't making a lot of progress in actually recruiting older workers."

There are a few efforts aimed at filling that gap. A group called Encore.org works to connect professionals with non-profits and local governments who need people with experience to take on short-term projects or fill less demanding roles, for example.

Related: Inequality among America's seniors is among worst in the world

Some employers, including the federal government, have implemented phased retirement programs that allow employees to work part-time at the end of their careers. Older workers with enough financial wherewithal will often try starting their own businesses as a bridge to full retirement, research has shown.

Advocacy groups are working to convince employers that older workers are worth keeping around, countering perceptions that they can't keep up with new technology or work with younger colleagues.

"We will be starting to educate publicly about the need to appreciate everybody's skill set," says Anna Maria Chavez, chief strategy officer of the National Council on Aging. "Experience and tenure is a great thing, and you don't want to destabilize your workforce."

Another thing that can help: Some training and a little bit of confidence. That's what Karon Malingo, another participant in the Senior Community Service Employment Program, learned upon being thrown into a job as an intake specialist at the program's office after seven unsatisfying years working in retail.

She calls herself a Luddite, but took quickly to managing spreadsheets and answering email, and now feels that she would have plenty of options.

"I feel so modern now. I have skills up the wazoo!" trills Malingo, 67, a slight woman with a gray pixie haircut. "They dropped me in the pool and I had to swim."