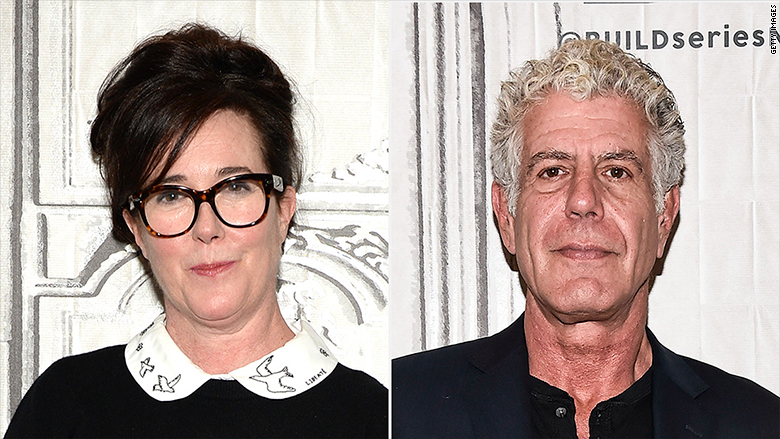

Two icons took their own lives this week, forcing the news media to grapple with one of the most painful and challenging subjects.

After news broke Friday that the roving journalist Anthony Bourdain had died of an apparent suicide, the Poynter Institute re-published a story detailing how the press often exacerbates matters in the ensuing coverage.

The story, written by Poynter Vice President Kelly McBride, was originally published in 2014. As if to underscore the recurring horror of suicide, McBride also shared the story on Tuesday, when the world learned that fashion designer Kate Spade had also taken her life.

News coverage of Spade's death, McBride said on Twitter, "is exactly the kind of news story that can lead to a contagion if the details are reported irresponsibly."

But days later, when the press had to confront yet another grim story in the death of Bourdain, McBride said she saw an improvement.

"I think most of the people who are covering Anthony Bourdain aren't making as many mistakes because they covered something similar earlier this week," she told CNN in a phone interview Friday.

"I think we're getting there," McBride said. "I think most organizations in the next 12 months will have these written in their code."

On Twitter, McBride listed a set of guidelines for reporting responsibly on suicide, including providing readers with "resources for people who need help." In the wake of Bourdain's death on Friday, many news outlets -- including CNN, where Bourdain hosted a show -- directed readers and viewers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Dr. John Draper, the executive director of National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, said he noticed an uptick in media outlets' promotion of the lifeline number (1-800-273-8255) following the death of actor Robin Williams in 2014. Williams' death was followed by the largest sustained spike in calls to the number, according to Draper.

"And that was entirely due to the media's reporting and the inclusion of the number," Draper told CNN. "That was probably the beginning of doing the right thing in a widespread way."

"The more ubiquitous the number is, the more people are calling," he said.

Related: How to get help for someone who might be suicidal

McBride also urged journalists to avoid lionizing the victim, oversimplifying the cause of death and sensationalizing the outpouring of grief. She also advised against wading into the explicit details of the means of death; "the less graphic and specific, the better," she wrote.

Details of Spade's death were quickly and widely reported. Reporting on those facts can become problematic in the online media environment, where news spreads like wildfire and is often accepted as truth before it is even verified. But adhering to that guideline may run counter to the journalistic impulse to provide readers with as much information as possible.

McBride said she saw some examples in the coverage of Spade's death "that did not adhere to the best practices, specifically because they mentioned the means of death and provided specific details in headlines."

She acknowledged the balancing act of reporting on the nature of a suicide but said that downplaying the exact cause of death, including keeping it out of headlines, can help prevent a contagion.

"I think you can report it minimally. You can put it low in the story," she said. "You don't have to keep repeating it in subsequent stories."

"Our duty is to inform, and I get that," McBride added. "Individual reporters can't really be responsible for that. Organizations have to own that. We have to create standards in organizations that are organization-wide."

Draper echoed that.

"You cannot not report on suicide. You have to report on someone like Anthony or Kate Spade when they kill themselves," he said. "But when anyone dies, the focus should not be on the cause of death so much as what they meant to the living and what they meant to people around them. The story of their life is so much more important than the story of their death."

McBride cautioned against overly laudatory coverage of celebrities who take their own lives -- a particular challenge in the case of two widely admired figures like Spade and Bourdain.

"It's really tricky," she said. "You read over the language you're using about the significance of his career and see if there are ways you can state it with fewer adjectives and adverbs. With Anthony Bourdain, you could say something like, 'He connected with an entire generation in exploring the globe,' as opposed to, 'He inspired an entire generation to embrace adventure.' There's a difference in tone. A lot of times in obituaries, we go for an over the top tone."

Still, McBride said that "we're likely to continue to see a contagion" following this week's news. On Thursday, the Center for Disease Control reported that suicide rates in the United States rose by 25% between 1999 and 2016.

Related: Remembering the life of Anthony Bourdain

That nearly two decade period included a number of celebrities who took their own lives, including Williams, whose death in 2014 was followed by a spike in suicides by a similar means. Coverage of Williams' death was filled with graphic descriptions of the suicide, including an infamous New York Daily News front page headline that said, "HANGED."

"Disrupting the cycle of a contagion is something we can help in journalism simply by making different choices," McBride said. "I'm not saying don't cover it, I'm just saying make a couple different choices when covering it, and add more context."

But Draper said he's taken heart in the increased awareness among members of the news media, particularly since Williams' death four years ago.

"I can't tell you how many folks in the media have said, 'How can we stop contagion?' And that is something I have not heard before, at least not to this extent," he said.

The contagion is being confronted elsewhere, too.

Samaritans, a British charity that provides suicide assistance and counseling, has its own guidelines for covering the matter. When it comes to reporting the methods, the group urges reporters to "avoid giving too much detail," particularly "any mention of the method in headlines as this inadvertently promotes and perpetuates common methods of suicide."

"Details of suicide methods have been shown to prompt vulnerable individuals to imitate suicidal behaviour," according to the group's guidelines, which note that such reporting runs the "risk of imitational behaviour due to 'over-identification.'"

Earlier this year, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), a press regulator in the UK, announced that it will be teaming up with Samaritans to provide assistance to journalists who are covering suicide.

IPSO said it will regularly publish blogs authored by Samaritans covering "the research around the reporting of suicide and key points for editors and journalists to consider," while also providing "practical recommendations for journalists." In addition, IPSO said it will offer its own set of guidance on the issue.

"Ultimately, we can only reduce the numbers of suicides each year if we continue to talk about the issue," said Charlotte Urwin, head of standards at IPSO. "Through information, training and guidance, IPSO can help journalists to cover this important topic without putting vulnerable people at risk."

How to get help: In the U.S., call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. The International Association for Suicide Prevention and Befrienders Worldwide also provide contact information for crisis centers around the world.

https://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

https://www.iasp.info/resources/Crisis_Centres/

https://www.befrienders.org/need-to-talk