Bill Carter is a contributor for CNN and a former television reporter for the New York Times. He is also the author of four books, including "The Late Shift," "Desperate Networks," and "The War for Late Night." The views expressed in this commentary are his own.

When he was an actor, Leslie Moonves, capable of a truly menacing glare, almost always played the villain.

He gave up the acting profession when he started to work as a television executive--and also, he always said, because he realized he wasn't a very good actor.

Well, who knows?

For the past 30-plus years, Moonves has performed at a very high level as an entertainment executive, ultimately and most consequentially, as the CEO of CBS; he was almost surely the most successful television executive of his generation. CBS, once a joke in the business, has become perhaps the last bastion of true broadcast network power. That was all Moonves's doing.

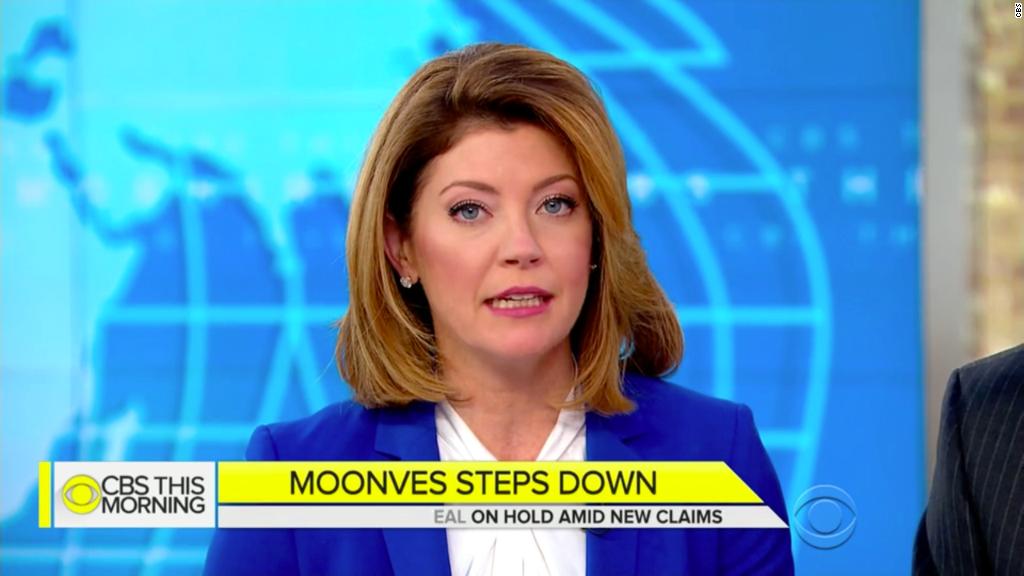

But as he leaves the network, undone by a torrent of stomach-turning accounts of vile acts of sexual predation, Moonves stands accused of a return to his roots. If even a portion of what a growing assemblage of women in Hollywood-- ranging from actresses to writers to producers, and even a doctor he happened to seek treatment from -- have said is accurate, Moonves seems to have played the really bad guy in an awful lot of disturbing episodes.

He continues to deny the worst of the incidents. I certainly was not a witness to any of them. I didn't know Moonves as a person. I covered him on a professional basis as a reporter for more than 25 years. In that time, I interviewed him countless times, in person and on the phone. He stood out from many other TV executives I have gotten to know mainly in his drive and his demeanor—and his success.

Related: Will Les Moonves leave with $0, $120 million, or something in between?

Moonves didn't have any of the jangly nerves of most TV programmers, who know they work on infinitesimally short leashes, among the shortest in corporate America. Instead, Moonves was always a full-throttle guy, ambitious and unashamed to admit it, hugely confident, hugely quotable, ferociously competitive, egocentric, with a penchant for using intimidation when he felt that would work.

I never felt the intimidation, maybe because I was not vulnerable, as employees were (and apparently women were, far more significantly.) For me, it was the professional relationship of a reporter and a subject of news. I never went out for drinks with him, or to ballgames, played golf with him, or shared any other private pursuit.

I never heard any credible account of acts like those that have now emerged. Of course, he had a nasty divorce, and married an on-air network employee after carrying on an open affair with her. Though hardly admirable, that did not rise to the level of suspicious behavior in Hollywood. And that second marriage, to Julie Chen, has seemed outwardly solid. Certainly, Moonves's public temperament mellowed in recent years.

In conversation, Moonves could be candid or cagey, charming or irascible. He liked some stories I wrote and hated others. That was the job and we both knew it.

Of course, I heard about his temper. Especially in early years at CBS, he was said to be volcanic at times. I wrote about some examples. Like a time one personal habit went too far. Though he stopped this long ago, he used to flick at his cheek with the back of his fingers as he spoke, sort of like Brando in "The Godfather." One time, I was told, as he worked himself into a lather about something at a CBS meeting, the flicking got so impassioned, flecks of blood began to sprinkle down the front of his white shirt.

Usually, his rage related to some competitive encounter. Moonves always had people he considered professional enemies, and something about them could set him off. Ted Harbert, who was a pal of Moonves and a sometime executive competitor at ABC and elsewhere, told me, "You poke Les, he'll hit you in the head with a frying pan."

That was a metaphor, I presumed. I never heard anyone at CBS say he had been physically aggressive, though he could be verbally abusive, to some people's extreme discomfort. Some of these tales had a mythical quality to them: the Hollywood boss biting off the heads of his underlings.

But those executives were also unusually loyal to him. Executives stayed at CBS for lengthy tenures, often their whole careers. They had reason to because they were well compensated. Under Moonves, CBS soared as a media enterprise. As stockholders, their fortunes soared as well.

Related: A stunning end to a historic run for Les Moonves

Even in private conversation, executives I spoke to respected Moonves' leadership. That certainly included some women, several of whom attained very high positions at CBS. Nina Tassler, for one, rose to the top program position at the network. Whether she or any another executive had much autonomy was another question. Every important thing at CBS, from the promos to the casting of major roles, had to get final approval from the Boss. But Tassler always officially praised Moonves and thanked him for the opportunity he had given her.

In the weeks since Ronan Farrow's original stunning piece about the accusations against Moonves, Tassler, interestingly, has not commented, and went out of her way to avoid comment at a public appearance last month.

Did she or other people at CBS know about these alleged episodes of sexual advances, abuse of power and intimidation that many women have now credibly described? None so far has admitted it.

It's possible that we were all watching the most effective performance of Leslie Moonves's life.

The show is over now.