For years, BlackBerrys were the only mobile devices corporate IT departments allowed past their gates. Now those heavily guarded doors are swinging wide open to all kinds of personal gizmos, including iPhones, iPads, Android gadgets and more.

The trend has obvious advantages: Businesses get to cut expenses by having their employees use their own phones and tablets, and employees get to carry around high-powered devices of their choosing. It also comes with a cost: The "bring your own device" phenomenon introduced a whole slew of vulnerabilities to corporate networks.

Big corporations are "offering up a way into their networks on a silver platter," says Georgia Weidman, CEO of Bulb Security, an information security consulting firm. "Every app you install on your mobile device could lead to compromise, every text message you receive. Every website you browse using your own device's mobile browser is possibly suspect."

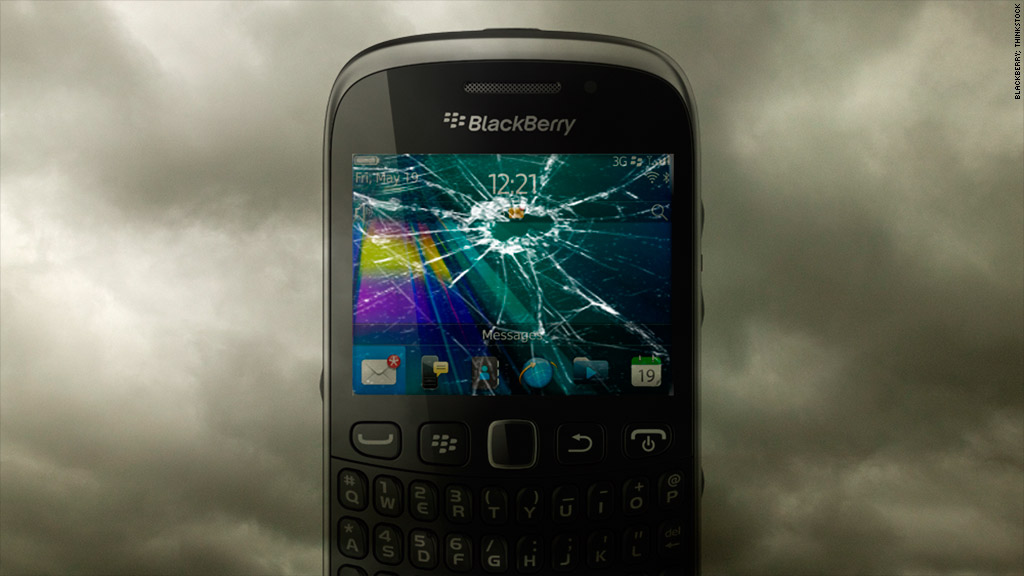

BYOD has been a growing trend over the past several years, but it rapidly accelerated this year as the floor gave out under BlackBerry. Research In Motion (RIMM), BlackBerry's creator, now makes up just 9.5% of the U.S. smartphone market, according to comScore, down sharply from 22% a year ago and 39% in 2010 -- when it was No. 1 in the market. Some companies are even banning BlackBerrys entirely: Yahoo (YHOO) recently cut them off in favor of new Apple, Google and Microsoft phones.

Research In Motion long had a reputation for making the most secure mobile devices on the market: "BlackBerry had the killer app, which was secure e-mail and secure messaging," says Lawrence Reusing, head of global mobile security for Imation.

Its rivals have caught up. Over the past few years, Apple (AAPL), Google (GOOG) and Microsoft (MSFT) vastly improved their mobile software's corporate-grade security protections to get their devices into BlackBerry's former territory.

But there's a bigger problem: Today's most popular smartphones are simply more powerful than the BlackBerrys of years past, giving their users more ways to unintentionally download something harmful.

"BlackBerry is a less functional platform, and 'less functional' and 'more secure' always go hand-in-hand," says Dave Aitel, president of security firm Immunity Inc. and a former NSA computer scientist. "I don't think the built-in protections are any greater on BlackBerry than on iPhone or Android. The browser was just terrible -- and it is still terrible to this day."

Reusing agrees. As companies toss out their aging BlackBerrys, they're bringing on devices that are inherently more risky.

"With advent of iPhone, and Android, you can now do a lot more on iPad than you ever could on your BlackBerry," he says.

Cyberattacks on mobile devices are on the rise, and cyberthieves are increasingly targeting mobile devices as a backdoor into corporate networks, according to Intel (INTC) subsidiary McAfee. If just one device has been compromised -- if a single employee clicks on a bad link, downloads a malicious app, or leaves the device at a bar -- attackers could get a free pass into the network.

Related story: Your smartphone will (eventually) be hacked

A recent study conducted by the Ponemon Institute found that 59% of corporations that allow BYOD report that their employees fail to lock their personal devices, and 51% experienced some form of data loss as a result. Without basic protections like passwords, anyone who picks up a lost or stolen device that's attached to a corporate network can access potentially sensitive data like e-mails and contact lists.

The risks of BYOD aren't just on the employee side. Corporations are taking a far too relaxed approach to the new trend, security experts say.

A recent PricewaterhouseCoopers study found that 88% of consumers use their own mobile devices for both personal and work purposes, yet just 45% of companies have a security strategy to address BYOD devices.

"BYOD came into the workplace a lot faster than organizations were prepared for," Reusing says. "It's difficult to have an organization secure a device it doesn't own and control."

Solving the BYOD problem is complicated, because smartphones and tablets aren't built like PCs. Most mobile devices place their software in silos, preventing one app from tapping into another. That's effective in preventing malicious software from spreading, but it presents a problem in designing things like third-party antivirus apps.

"Antivirus has far less benefit on mobile than on the PC," said Chris Burchett, co-founder of security firm Credant Technologies. "That's not where mobile OS makers want to spend their resources."

Some of proposed security fixes include mandating password locks and giving corporate IT departments the ability to remote-wipe employees' phones. That can bring in a whole new set of challenges, though: Would you want to give your employer the ability to delete data off a personal device you own?

Get ready to deal with that kind of question. As Stu Sjouwerman, CEO of security training firm KnowBe4, puts it: "With BYOD, our company employee has become the 'thing' that needs to be secured."