Online voting is taking off in local elections, particularly overseas. But Americans shouldn't expect to vote for the president on their laptop or iPad anytime soon.

The battle over whether to digitize the voting process has become a full-blown war in the United States, even as countries like Canada, Norway and Australia have increasingly adopted online systems. Proponents say going digital will boost voter turnout, while naysayers cite hacking and other security threats as risks too great to overcome in the near future.

"It's such a different world than it was 20 years ago, and yet very little has changed in our voting process," says Rob Weber, a former IT professional at IBM (IBM), who started the blog Cyber the Vote in 2010.

Like many supporters of online voting, Weber points out that many young Americans don't vote. Bringing the voting process to a format they're familiar with -- a website on a PC, tablet, or even a mobile phone -- would overcome the "enthusiasm gap," he believes.

But that argument hasn't been enough to bring online voting into the mainstream. For that, Weber places the blame squarely on election officials whom he says aren't interested in changing the status quo.

"They find online voting culturally distasteful," Weber says. "They bring up theoretical hacking situations in order to make people afraid of the concept of change. And unfortunately it works."

Security researchers don't think those concerns are merely theoretical. Michael Coates, chair of the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) and director of security assurance at Firefox maker Mozilla, says hackers will attack anything worth hacking.

"It's guaranteed that such a system [online voting] would be attacked, for sure," Coates says. "All important systems, from financial to government, face skilled hackers. There are security flaws in every system; it's a matter of how you detect and respond to them."

Home PCs, in particular, are susceptible to a myriad of cyberattacks that could be used to alter a user's vote.

"Until we can reliably foil malware and viruses -- and who knows when that will be -- it's hard to consider a system in which we vote from our home computers," Coates says.

Such issues have felled some past attempts at online voting in the United States.

In 2004, the military began testing the Secure Electronic Registration and Voting Experiment (SERVE), which would have let service members stationed overseas vote online in the general election. But Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz scrapped the plan after government-commissioned studies warned of extensive security flaws.

Another oft-cited failure came in 2010, when Washington, D.C., conducted a pilot project to allow overseas or military voters to download and return absentee ballots over the Internet. Before opening the system to real voters, D.C. invited the public to evaluate whether the system could be hacked.

It was. Within 36 hours of going live.

A University of Michigan team "found and exploited a vulnerability that gave us almost total control of the server software, including the ability to change votes and reveal voters' secret ballots," professor J. Alex Halderman later wrote in a blog post about the hack.

Halderman termed the system "brittle" and proclaimed online voting too dangerous to implement anytime soon.

"It may someday be possible to build a secure method for submitting ballots over the Internet, but in the meantime, such systems should be presumed to be vulnerable based on the limitations of today's security technology," he wrote.

Such high-profile debacles are a difficult obstacle for online voting companies like Everyone Counts, says CEO Lori Steele.

"The problem with the D.C. hacking is that it was a less-than-mediocre system run by people who had no experience," Steele says. "When people use it as an example, it's like, c'mon -- those issues were all security 101."

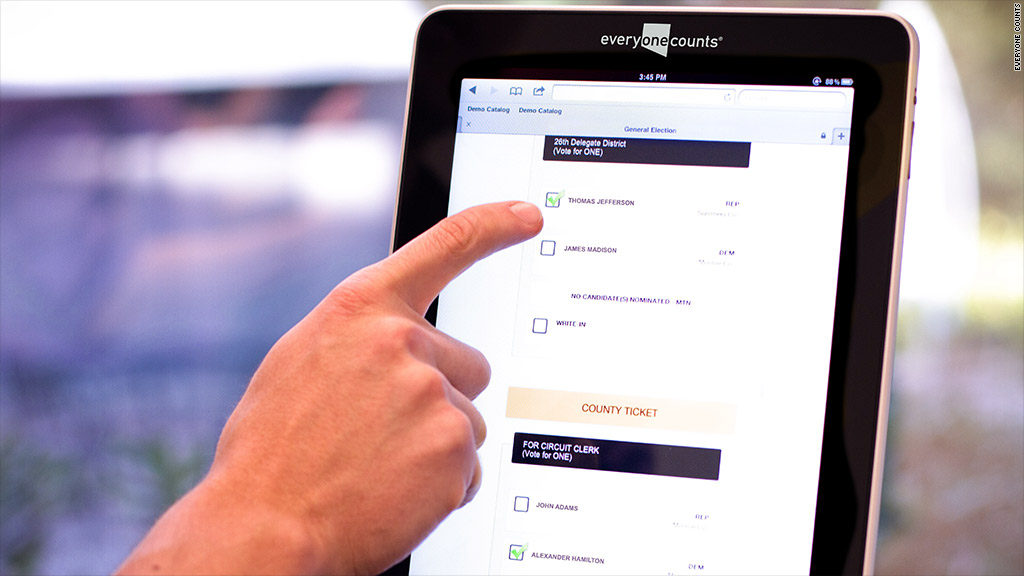

Bad PR for any online voting attempt undermines the entire cause, Steele says. Still, California-based Everyone Counts has run online elections for local and municipal contests in U.S. locations including West Virginia, Honolulu, El Paso, Chicago and Washington state, in addition to the United Kingdom and Australia.

Everyone Counts uses "military-grade encryption" for its ballots, and can also provide a paper trail for clients who want it, Steele says. A "transparent code" policy allows any client to inspect the company's source code.

While Steele admits that online voting, like any system, is susceptible to attacks, she thinks the sheer number of devices in the wild would make it difficult for would-be hackers to hit their targets.

"They don't know which PCs or tablets or phones will be used for voting," Steele says. "Plus, people talk about paper being the Holy Grail of security, but that is so far from reality."

The biggest limitation of paper ballots was on display last week, when Hurricane Sandy decimated parts of the northeastern United States. The storm's destruction cut many voters off from their scheduled polling station.

On Saturday, New Jersey announced that displaced storm victims will qualify as "overseas voters," meaning they are eligible to vote via e-mail or fax.

"The storm was awful, but it could serve as a wider reminder that we need to reform the system," says Michelle Shafer, director of communications at Scytl USA.

Scytl's Spanish parent company has conducted online voting in over 30 countries worldwide. In the U.S., it's slowly gaining steam. The company has completed online "ballot delivery" -- digitally delivering a paper-ballot-like form that voters can fill out and submit -- in six U.S. states. Those digital ballots are typically used by military members and overseas residents. It has also run direct online voting for local elections in West Virginia, Florida and Alaska.

"I don't think we'll be voting online by [2016's general election], but my hope is that we'll continue to take slow and measured steps toward that eventuality," she adds.

While the United States takes it slow, countries like Canada and Norway continue to expand online voting.

Dean Smith, president and founder of Canada's leading online-voting firm, Intelivote, says the divide between his home country and the United States is vast. Popular Canadian labor unions have used online voting for years -- which means users have grown accustomed to the process -- and the country's ballots tend to be far less complex than those in the United States.

"In general, people here see the benefits of online voting and there's an acceptance," Smith says of Canada. "The U.S. would be a great coup, but there are so many academics who made their name by being naysayers. There's so much fighting about it. Right now, we don't need the additional problems."