The tantalizing promise of a single button that prevents ads from tracking your online behavior is fizzling fast.

More than nine months after the Obama administration, digital advertisers, browser makers and privacy advocates agreed in principle to create a "Do Not Track" mechanism for Web browsing, the tool is no closer to becoming a reality than it was in February. In fact, the entire plan is on life support.

The various parties have been sitting around a table every Wednesday -- both virtually and, on six occasions, physically -- trying to reach a consensus on how a Do Not Track button would be implemented.

After months of wrangling, the groups still can't even come to an agreement on what "tracking" means and includes. The advertising industry wants to hang on to the current business model of targeted advertising, which tailors ads to users based on their browsing activity. Privacy advocates and lawmakers believe people should easily be able to opt out of that. The one thing all sides agree on is that they are hopelessly deadlocked.

Privacy advocates accuse the advertising industry of unfairly stalling the process.

"The advertisers have been extraordinarily obstructionist, raising the same issues over and over again, forcing new issues that were not on the agenda, adding new issues that have been closed, and launching personal attacks," said Jonathan Mayer, a Stanford privacy researcher and Do Not Track technology developer who is involved in the negotiations.

"We have made, maybe, inches of progress," he said. "This continues to be a stalemate."

On the flip side, the industry claims that privacy supporters are trying to impose overly restrictive changes that could seriously damage the digital advertising business.

"We have a real concern about using a sledgehammer for a flyswatter problem," said Marc Groman, executive director of the National Advertising Initiative, a coalition of online advertisers. "Do Not Track will have a disproportionate effect on our stakeholders."

The World Wide Web Consortium, colloquially known as the W3C, is moderating this increasingly fractious and seemingly endless debate. In an effort to blast through the impasse, the W3C this week hired Peter Swire, an Ohio State University law professor and a former privacy official for the Obama and Clinton administrations, as the working group's new chair.

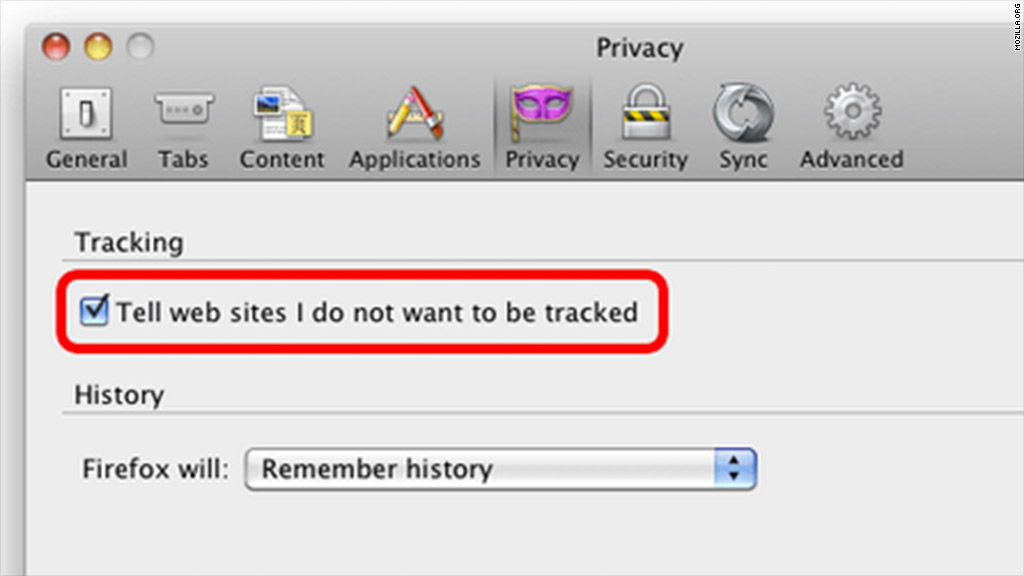

W3C's Hail Mary hope is that Swire can quickly build consensus. Currently, most major browsers include a Do Not Track button, but without any agreement on how Do Not Track should work, the button doesn't do anything.

An initial plan to have Do Not Track up and running by end of the year is looking impossible.

Part of the problem is the huge number of stakeholders with competing interests. For instance, smaller advertisers argue that Do Not Track favors large players like Google (GOOG), AOL (AOL) and Yahoo (YHOO), each of which has a vast content network of its own. Even with Do Not Track turned on, those giants will still be able to track users' behavior on their own sites -- just not across the rest of the Web.

Another wrench in the gears came when Microsoft (MSFT) opted to turn Do Not Track on by default in its latest version of Internet Explorer. That threw negotiations into a tizzy over which default -- "on" or "off" -- best represents a user's intent. (That's the official line. The disagreement is really over whether the advertising industry is still willing to play along with Do Not Track if the default setting is "on.")

"Why is this taking so long? Because people don't want to budge," said Ian Jacobs, spokesman for the W3C. "It's like a budget deficit committee meeting."

The W3C is determined to break the deadlock, and it believes it has a solution -- albeit an undesirable one.

In the agenda for its latest face-to-face meeting, held last month, the group finally admitted that "many issues cannot be resolved in a way that does not raise any objections." So the W3C plans to start pushing all parties forward on the path of least resistance.

"We always seek consensus, but when we can't, we get votes and make decisions," Jacobs said. "Saying 'I don't like this' is not going to be considered a strong objection. We're not going to be held hostage when a group can't make progress."

But even the W3C acknowledges that all parties will have to voluntarily agree to honor Do Not Track once the negotiations end. If the final decision isn't unanimous, some advertisers and browsers may choose to simply ignore Do Not Track protocols.

That's why some privacy proponents are advocating for a more nuclear option: ad blocking.

"Do Not Track was supposed to be the olive branch. It was the polite solution," said Stanford's Mayer. "If we don't get an agreement, then we'll just start blocking those guys."