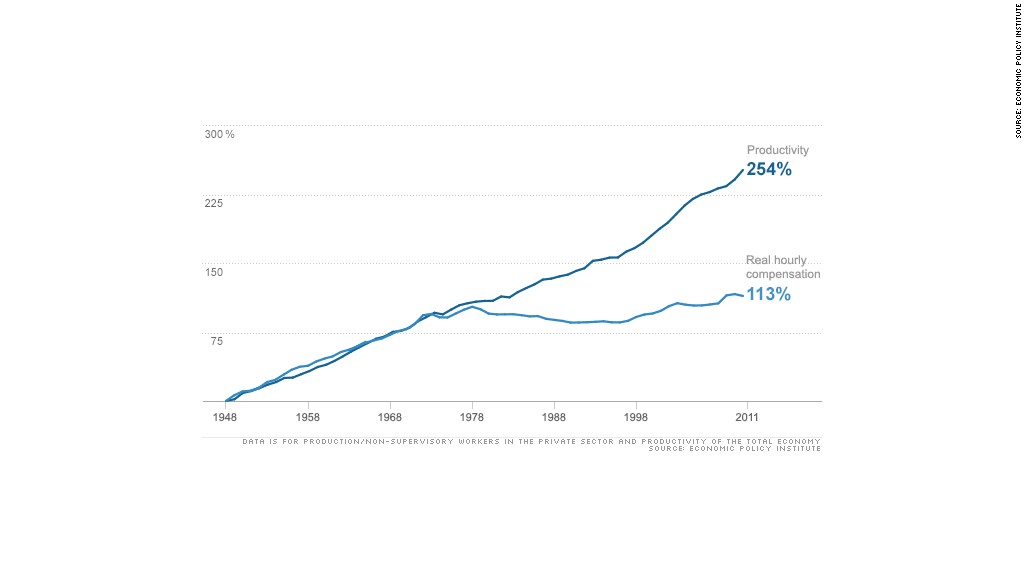

Companies are on a tear in terms of productivity and profits, but they aren't sharing much of the gains with their workers.

The gap between hourly compensation and productivity is the highest it's been since just after World War II. This divergence is one of the major drivers of the nation's growing income inequality.

"A bigger share of what businesses in the U.S. are producing is going to the owners of the firms and the people who lent money to the firm, and a smaller share is going to workers," said Gary Burtless, senior fellow in economic studies at The Brookings Institution.

(Related: Stressful jobs that pay badly)

Productivity, which measures the goods and services generated per hour worked, rose by 80.4% between 1973 and 2011, compared to a 10.7% growth in median hourly compensation, according to the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, which crunched the numbers last year.

That's a marked shift from the trend between 1948 and 1973, when productivity and compensation grew in tandem.

The main reason for the wider gap is a dampening of wage growth in recent decades, both among the college-educated and those without degrees, said Lawrence Mishel, the institute's president. Global competition and national deregulation have kept compensation down, while the decline of union power weakened workers' ability to bargain for higher pay.

The split has been particularly acute since the beginning of the 2000s, when wage growth flattened. And now, with unemployment hovering around 8%, workers feel lucky to have a job and aren't pressing as much for raises.

"Companies are using that power to get a better deal out of workers," Burtless said.

Employers are achieving their gains with fewer workers, too. U.S. economic activity is now 2.5% higher than it was when the recession began in late 2007, but there are more than 3 million fewer workers on the job, said Mark Perry, a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

Looking at hourly compensation alone doesn't tell the whole story, though, because it doesn't include benefits. They make up about 30% of a worker's total compensation, and their cost has been rising over time, Perry said.

He attributes the gap to market forces, and he expects it will narrow as the economy recovers. As things improve, the labor market will tighten and companies will raise wages, Perry said, pointing to the energy boom in North Dakota, which has prompted employers there to boost compensation.

"It's just taking a while," he said.