More than $350 billion a year. That's how much the federal government spends on the nation's two largest safety net programs, Medicaid and food stamps.

Medicaid provided health coverage to more than 70 million people -- about one in five Americans -- for at least one month in 2011. Food stamps helped feed nearly 47 million low-income Americans a month, on average, last year.

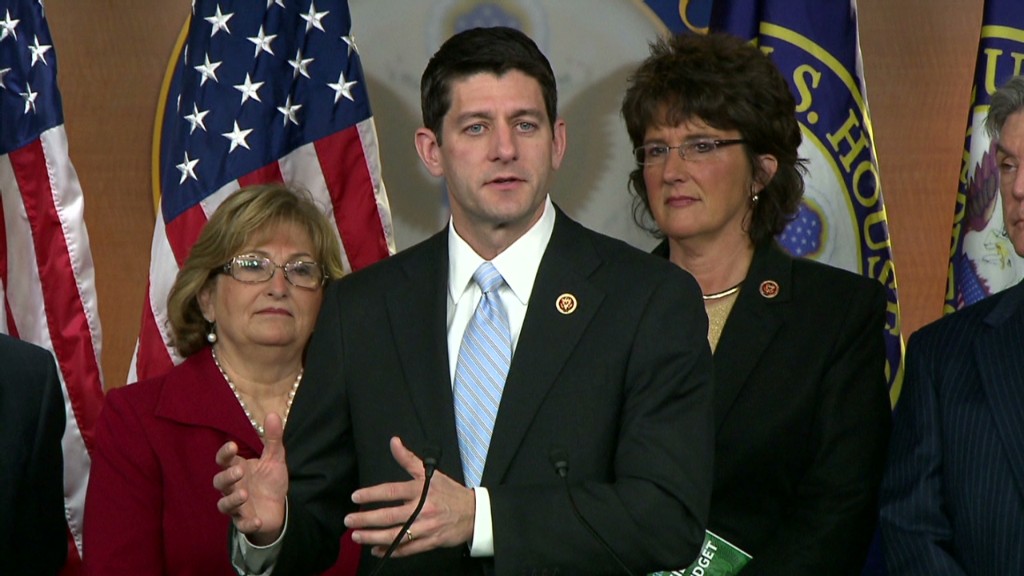

Rep. Paul Ryan wants to overhaul these safety net programs by giving more power to states and empowering recipients to get off of government aid. In the House Republican budget released Tuesday, Ryan once again proposed turning Medicaid and food stamps into block grants, which would give states more flexibility to tailor the programs to their residents' needs.

Critics of Ryan's plan argue this would also minimize federal support of these programs, which they say are crucial to keeping poor people afloat -- especially in economic downturns.

Here's a closer look at these safety net programs.

Medicaid: Enrollment jumped more than 13% during the Great Recession, according to federal data. While eligibility varies by state, most of those covered are poor children, the elderly and the disabled. Few other adults are covered, with the median income threshold for eligibility being 61% of the poverty line for working parents and 37% for jobless ones. Only a handful of states extend benefits to childless adults who are not disabled or elderly.

Medicaid spending totaled $432 billion in 2011, up 30% in just four years. The federal government covered about $275 billion and states picked up the rest. Spending per participant came in at nearly $7,000.

The Medicaid program is about to get a whole lot bigger. As part of the Affordable Care Act, states can opt to expand Medicaid coverage to all residents earning less than 138% of the poverty line with the federal government picking up 100% of the tab for the first three years. About half of states have agreed to expand Medicaid or are likely to do so.

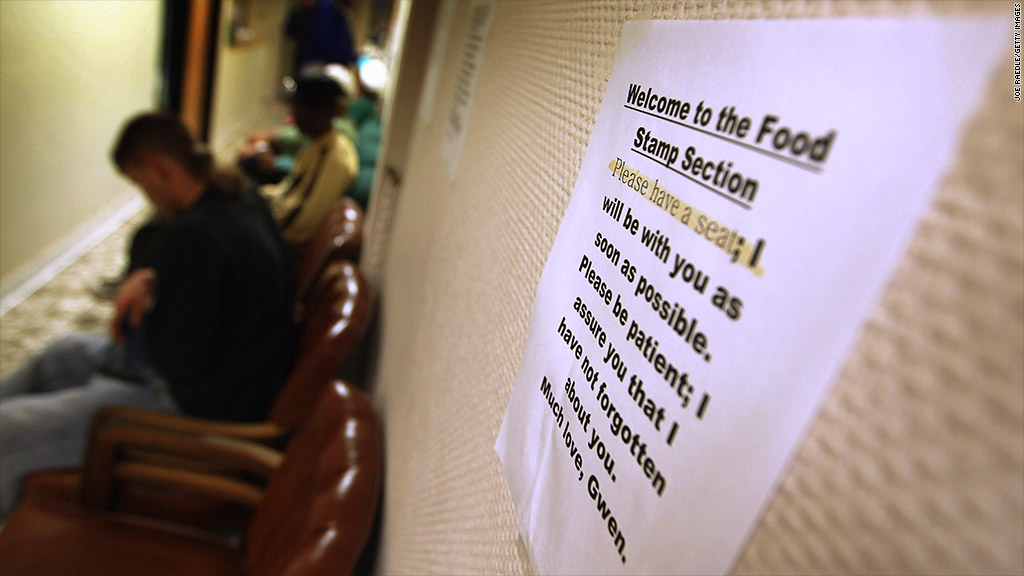

Food stamps: More people flocked to the food stamp program during the Great Recession as well. Some 46.6 million people, on average, received this assistance in 2012, up 77% over five years, according to federal data. The average monthly benefit was $133 per person.

Nearly 72% of participants are in families with children, while more than a quarter are in in households with seniors or the disabled, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. To be eligible, participants generally must have gross monthly income at or below 130% of the poverty line, or $2,069 for a three-person family in 2013, and assets of $2,000 or less. Households with elderly or disabled members have different criteria.

Spending on food stamps totaled about $78 billion in 2012, up 136% from five years ago. But costs are expected to come down as the economy recovers and more people get jobs, lifting them above the eligibility limits.

Related: Republicans revive Medicare subsidy plan

Now comes the hard part: How to overhaul these programs for both the good of the nation's budget and the poor that rely on this safety net.

Turning Medicaid into a block grant would reduce spending on Medicaid by about $810 billion over 10 years -- the figure was originally $756 billion but was later updated -- and on food stamps by about $135 billion, according to Ryan's budget plan.

The main fear among advocates for the poor is that block grants would curtail federal support of these safety net programs, particularly during economic downturns when enrollment rises. Since states would receive a fixed amount, they would likely have to cut eligibility or benefits to stay within the grant level, as opposed to the current system, where funding is open-ended and depends on how many people apply.

"When you talk about slashing the safety net to save it, it's hard to call that anything but Orwellian," said Elizabeth Lower-Basch, senior policy analyst at CLASP, which focuses on policy for the poor.

Many conservatives, however, argue that states are in the best position to know the needs of their low-income residents and can tailor the federal programs most efficiently to them. Block grants can also cut out some of the costly bureaucracy at the federal level.

"There's a big difference in being poor in New Mexico and being poor in Illinois," said Veronique de Rugy, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center, a free-market think tank at George Mason University. "A lot of these poverty needs are only known at the local and state levels."