In early 2010, Nish Bhalla sat down at his computer with one objective: steal a huge amount of money from a bank.

It wasn't a typical heist. Bhalla is the chief executive of Security Compass, a company that tests security systems at banks, retailers, energy companies and other organizations with sensitive data. His clients -- including the bank branch in the United States that he targeted in his 2010 attack -- pay him to break into their systems.

It can be easier than most people think. The alleged thieves who made headlines last week for their $45 million bank heist used a similar type of attack that "created" money out of nowhere.

Bhalla talked CNNMoney through his caper. Here, in four easy steps, is how he made himself into a millionaire.

Step one, get access. Bhalla had one big advantage on actual thieves: His client gave him access to the bank's internal network. For real-world crooks, there are some surprisingly easy ways to get in.

It's possible, Bhalla said, to gain access in some places simply by logging on to the bank's wireless network -- an amenity more and more banks are providing as a service to customers. Once you're on the bank's Wi-Fi, the internal and external networks are frequently not segregated enough. It can be possible to fool the bank's other computers into thinking that your computer is a bank computer, a process known as "arp spoofing."

Another on-ramp: Someone posing as a janitor could insert a thumb drive into a teller's system and reboot it using a new operating system, which would enable them to access the hard drive of the teller's system. From there, user names and passwords are often readable.

Because he could simply log straight into his client's network, Bhalla and his assistants skipped the "get physical access" step and dove straight into finding the money.

Step two, start exploring. Bhalla used "sniffer" software, available online for free, to map out which of the bank's systems were connected to each other.

Then he "flooded" switches -- small boxes that direct data traffic -- to overwhelm the bank's internal network with data. That kind of attack turns the switch into a "hub" that broadcasts data out indiscriminately.

The machines that the tellers use quickly became Bhalla's prime target. Again, the sniffer software was deployed to look for login information and passwords in the data flood. Eventually, one hit. He was inside a teller's machine.

Gallery: Scenes from a $45 million bank heist

Step three, move up the ranks. Amazingly, the information being sent between the tellers' computers and the branch's main database was not encrypted. This meant passwords and bank account numbers were all out in the open.

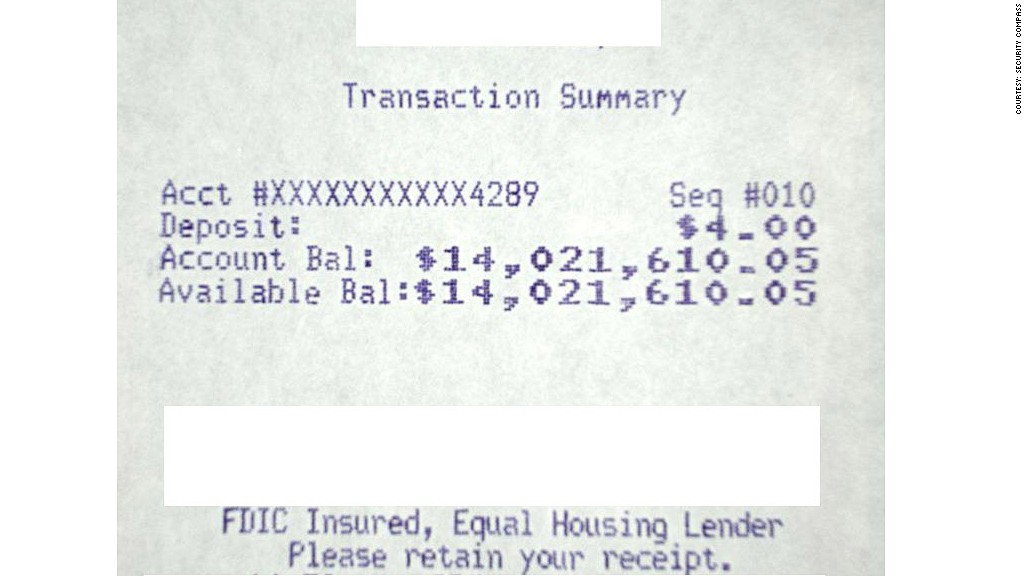

Step four, cash in. Rather than steal money from depositors' accounts, Bhalla just invented a new account for himself.

"We went into the database where the accounts are and set up an account with $14 million," Bhalla explained. "We just created $14 million out of thin air."

If he wanted to, he could have walked into any bank branch, transferred the money to an offshore account, and never have had to work again.

Instead, he went to an ATM to print out a record of his ill-gotten wealth.

"The bank executives were extremely surprised," Bhalla said. "Their faces were shocked."

The bank promptly deleted Bhalla's bounty, he said, and took steps to shore up its network.

In the heist that came to light last week, federal officials say the thieves hacked into networks at firms that process transactions for pre-paid debt cards and manipulated accounts to create high spending limits. From there, it was just a matter of making physical debt cards for those accounts and going around to ATMs to withdraw the cash.

"They just updated the database with that debit-card information," Bhalla said. "That's how simple it was."

In many cyber bank heists, including the recent $45 million scam, it's hard to pin down who is ultimately liable for any losses.

It's typically not individual customers. U.S. law protects consumer checking and savings accounts from losses stemming from fraud. Business accounts, though, have fewer protections.

Bhalla said some financial institutions have insurance to cover the losses -- but he noted that insurance companies are reluctant to issue policies with high coverage limits because the risks in this area area still poorly understood.

In the end, he said the losses are likely borne by a combination of the company, insurance firms and governments.