When two warring sides can't even agree on what "tracking" means, it's not surprising that little progress has been made toward launching a single browser button that prevents advertisers from tracking your online behavior.

Nearly two years after the Obama administration, digital advertisers, browser makers and privacy advocates agreed in principle to create a "Do Not Track" mechanism for Web browsing, the various parties still have not agreed on a basic framework for the tool. In an effort to salvage Do Not Track, leaders of the working group shepherding the agreement put their collective foot down on Monday.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), which is moderating this increasingly fractious and seemingly endless debate, said that it has chosen a foundation upon which all other discussions about Do Not Track will be based.

All the group needs to do now is hammer out 25 major disagreements about that foundation's "base text," including what kinds of data can be collected, how advertisers can identify users, how users' information is stored, and the very the definition of the word "tracking." No biggie.

Choosing a framework might technically constitute a step forward for Do Not Track, but the reality is that the besieged tool is no closer to seeing the light of day.

"The parties are now further apart on the negotiations than they ever had been," said Jonathan Mayer, a Stanford privacy researcher and Do Not Track technology developer who is involved in the negotiations.

Related story: Do Not Track is dying

The groundwork that the W3C chose was based on a draft that the organization's Tracking Protection Working Group cooked up in June. Both privacy advocates and digital advertisers raised objections to the draft, but it was considered the working agreement -- until the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA), an industry trade group, proposed sweeping changes to the draft late last month.

In its ruling on Monday, the W3C said the advertisers' proposal muddied the already well-murked waters about what tracking would entail. Under the DAA proposal, advertisers would still be able to profile users and target advertisements to them -- even if those users had turned on Do Not Track in their browsers.

That fails to meet the widely understood meaning of Do Not Track, the W3C said.

"There would be widespread confusion if consumers select a Do Not Track option, only to have targeting and collection continue unchanged," wrote Matthias Schunter and Peter Swire, co-chairs of the tracking protection working group.

DAA released a written statement saying that its proposal was "true to our 2012 White House agreement, and provides real choice to consumers."

So what happens now?

The W3C said it won't entertain any more discussion over the base text except for "polishing and editing" of the language.

Some working group participants aren't optimistic about where things are headed.

"I don't see a credible path forward for the group," Mayer said. "The June draft goes too far, according to DAA, but the privacy advocates say it doesn't do anything we want Do Not Track to do."

The group is supposed to come forward with its final proposal at the end of the month, but no one realistically expects that to happen.

More problematically, the sides with the real power here -- the DAA and browser makers -- can simply choose to ignore the W3C's standard if they don't agree with it. Two of the largest browser makers, Google (GOOG) and Microsoft (MSFT), just happen to control two of the largest advertising networks.

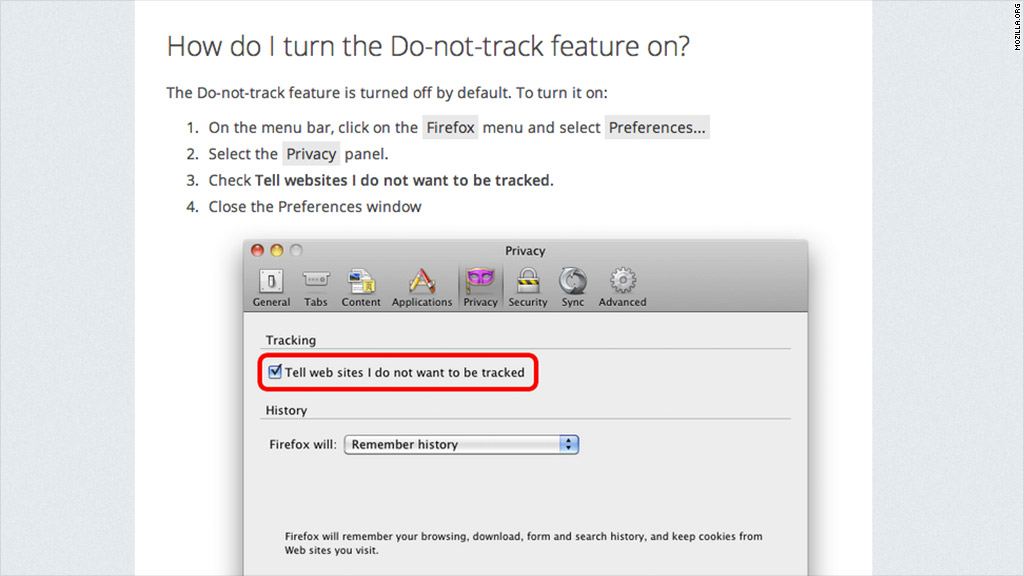

For now, Do Not Track is practically dead in the water, and some browsers are coming out with their own solutions. Mozilla, for example, said it will implement a feature in Firefox that blocks all third-party cookies. That would effectively block most tracking.