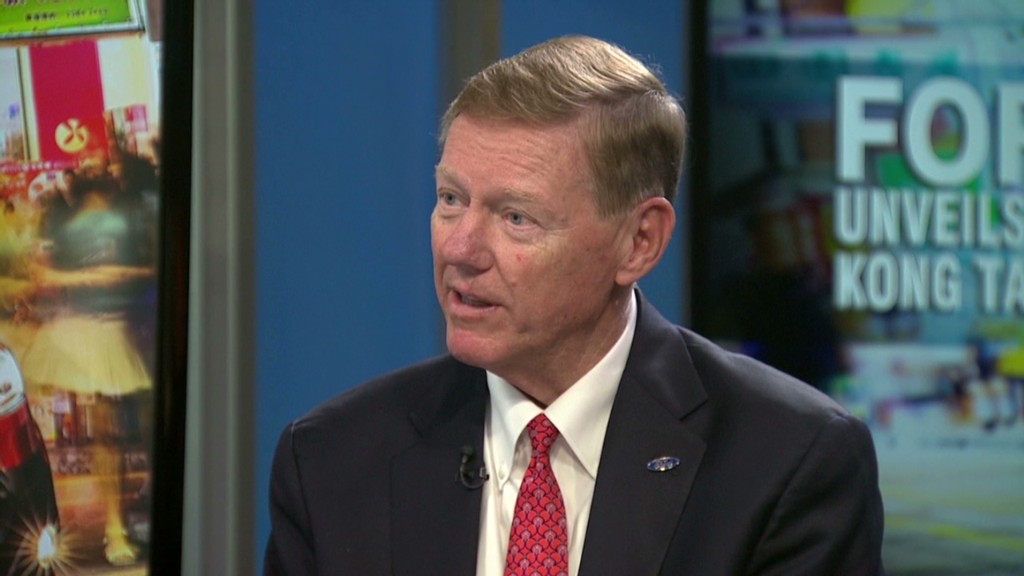

Ford CEO Alan Mulally tried Thursday to damp down reports he's preparing to leave the automaker to take the top job at Microsoft. But his denial doesn't necessarily rule out a move.

In a call with analysts to discuss Ford's strong third-quarter results, the very first question was about talk in the media that Microsoft (MSFT) wants Mulally to replace outgoing CEO Steve Ballmer. Mulally answered that his plans to stay at Ford until "at least 2014" haven't changed.

"I'm clearly excited and honored to continue to serve Ford," he said.

But when asked by a reporter if he had talked to Microsoft, he refused to answer the question, saying he would not comment on speculation. When asked what the chances were that he'd stay at Ford beyond 2014, all he would say was "our plan has not changed."

Ballmer, in announcing his retirement In August, said he would leave within the next 12 months. So Mulally's previously stated departure plan doesn't necessarily rule out his moving to the software maker.

Related: Fortune's Brainstorm podcast with Alan Mulally

Last year, when Ford disclosed Mulally's plans to stay through 2014, it named Mark Fields as president, a position that hadn't previously been filled. He is seen as the likely successor to the 68-year old Mulally.

Mulally has been Ford (F) CEO since 2006, joining the company from the commercial aircraft unit of Boeing (BA). He is widely credited with helping Ford avoid bankruptcy and the federal bailout that rivals General Motors (GM) and Chrysler Group endured in 2009. Under his leadership, Ford recaptured the No. 2 spot in U.S. car sales from Japanese rival Toyota (TM).

Related: 8 reasons why Mulally is better for Motown than Microsoft

Ford shares were higher in Thursday trading after it reported a record third-quarter pretax profit of $2.6 billion, up 19% from a year earlier. Revenue was up 12% on an increase in the number of vehicles sold worldwide.

The company was able to trim its ongoing losses in Europe and raise its earnings guidance. It did report a drop in net income, but that was due to severance costs from plant closings in Europe and a charge for a shift in white-collar pension plans.