The age of walking, climbing, driving robots is here -- but they're more toddlers than terminators.

They're slow. They trip and fall. Some even break their ankles or wrists.

The latest in robotics was on display the past few days at a racetrack just south of Miami, Fla., part of a $2 million competition funded by the U.S. military.

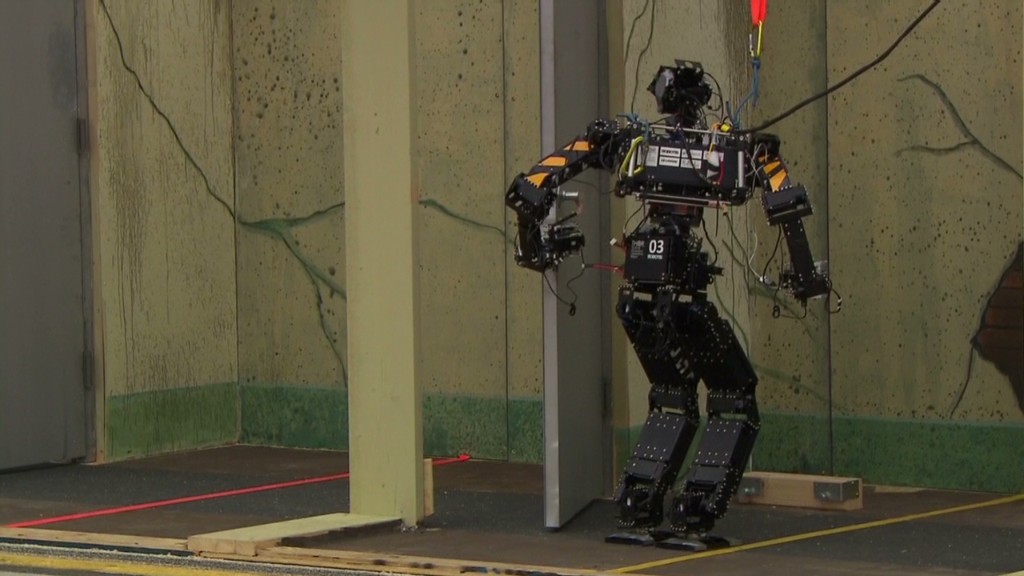

Engineering teams from high-tech companies and top universities showed off their designs, ranging from crawling models that look like spiders to heavy, hulking humanoids.

In all, 13 teams were competing for a $2 million award from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to be handed out next year.

Related: Google moves into military robotics

Competitors ranged from well-funded researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to hobbyists with Team Mojavaton in Colorado. They even came from abroad, including the Japanese startup Schaft (recently bought by Google (GOOG)) and Hong Kong University.

Throughout the demonstrations, the smell of oil hung in the air as robots made their way across test tracks. The aim was to test how well the machines could open doors, turn valves and keep their balance on uneven terrain.

The engines of some of the robots made a low hum, while others let off a high-pitched wail.

There were seven copies of the Atlas robot -- a two-legged, 300-pound creation by Boston Dynamics, which was acquired by Google last week. All looked alike, but each performed differently, because the software teams had designed different versions of its brain.

Related: 7 robots too expensive (or lethal) to own

A robot called Thor, built by Virginia Tech, looked oddly human while driving a four-wheeled buggy through a winding track -- its right arm turning the steering wheel and its left arm hanging casually off the side.

In fact, many engineers are racing to build robots with human-like dimensions and functionality so they can step through doorways, climb ladders and turn pressure valves.

The need for such robots was made urgent in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in Japan, when cleanup crews needed machines to venture into zones too dangerous for humans, said Arati Prabhakar, head of DARPA.

Engineers say robots able to perform simple human tasks would lead to applications well beyond rescue and disaster mitigation, however.

The scientists building these bots see a robust future for robotics in home health care and precision manufacturing, but they are leery to predict when that will happen.

Even if robotics has a long way to go, Google's entry was seen by those at the DARPA challenge as a sign the field is about to explode with advancement.

"This robotics challenge will change the way people perceive humanoid robots," said Dennis Hong, a mechanical engineering professor at Virginia Tech. "I envision them doing dishes, talking out the trash, doing the laundry. The future is quite near, but we've got a long way to go."