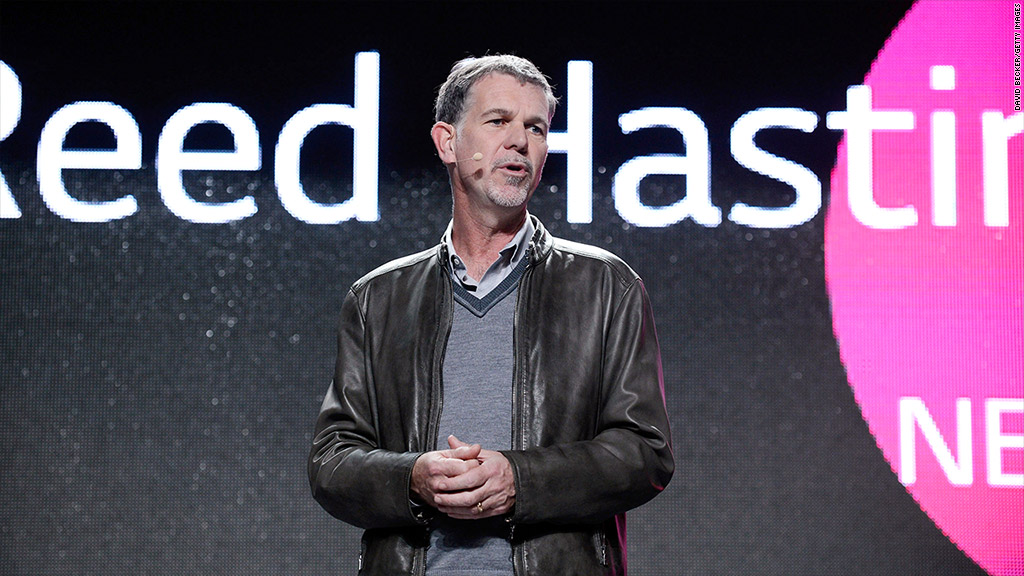

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings is hopping mad at the country's biggest Internet service providers. But they've got a bone to pick with him as well.

Hastings sounded off Thursday on the likes of Verizon (VZ), Comcast (CMCSA) and others, accusing them of "sacrific[ing] the interests of their own customers" in demanding fees to ensure quick delivery of content from Netflix (NFLX) and other data-intensive services. AT&T (T) fired back a day later, calling Hastings' argument "arrogant" and "self-righteous."

The dispute flared up earlier this year following news that Netflix streaming speeds for customers of major ISPs were slowing, as these firms attempted to extract a fee from Netflix in exchange for connecting directly to their networks and resolving the issue.

Netflix announced an agreement with Comcast last month under which it will indeed pay for a connection, and has been in talks with Verizon as well.

Hastings said his company was engaging in these talks "reluctantly." He accused the ISPs of abusing their market power and short-changing customers.

Related: New chapter begins in net neutrality fight

But the ISPs tell a very different story. They point to the fact that Netflix generates a massive amount of data consumption -- around a third of traffic online during peak hours -- while sticking them with the costs of upgrading their infrastructure to handle the ever-increasing traffic.

"It's simply not fair for Mr. Hastings to demand that ISPs provide him with zero delivery costs -- at the high quality he demands -- for free," AT&T senior executive vice president Jim Cicconi wrote in a blog post.

"Nor is it fair that other Internet users, who couldn't care less about Netflix, be forced to subsidize the high costs and stresses its service places on all broadband networks."

The National Cable and Telecommunications Association says just one percent of broadband subscribers -- primarily heavy streaming-video users -- consume nearly 40% of bandwidth going into homes.

Other big tech companies, including Microsoft (MSFT), Google (GOOG) and Facebook (FB), already have paid-connection deals with big ISPs. Comcast vice president David Cohen said in response to Hastings that these arrangements "have been an essential part of the growth of the Internet for two decades."

Dan Rayburn, an industry analyst at Frost & Sullivan, says it's not clear that the ISPs are to blame for customers' lagging Netflix speeds. In a blog post Friday, he noted that Netflix has the option of rerouting the traffic it sends to ISPs when congestion occurs at one connection point.

The heart of the problem is that high-speed Internet networks are extremely expensive to deploy. There aren't many companies with the resources to do it, and there isn't enough competition in most regions to push ISPs to quickly upgrade their infrastructure.

Paid-connection deals like the one between Comcast and Netflix are part of the way the broadband industry wants to address this issue.

"As we all know, there is no free lunch, and there's also no cost-free delivery of streaming movies," AT&T's Cicconi wrote. "Mr. Hastings' arrogant proposition is that everyone else should pay but Netflix."

But Hastings says this cost-sharing doesn't make sense if the ISPs aren't also willing to share subscription revenue.

"When an ISP sells a consumer a 10 or 50 megabits-per-second Internet package, the consumer should get that rate, no matter where the data is coming from," Hastings said in his blog post.

Related: Court strikes down net neutrality rules

ISPs have accused Netflix of "dumping" data onto their networks, a characterization that Hastings rejected.

"Netflix isn't 'dumping' data; it's satisfying requests made by ISP customers who pay a lot of money for high speed Internet," Hastings wrote. "If this kind of leverage is effective against Netflix, which is pretty large, imagine the plight of smaller services today and in the future."

Going forward, broadband providers would like to move to a tiered pricing structure for customers depending on how much data they consume, similar to those offered by mobile carriers.

"[I]t's unfair to ask lighter users to subsidize super-user activity," the NCTA says.

But part of that formula will likely involve letting content providers subsidize consumer data consumption that goes toward their services. AT&T announced this kind of "sponsored data" program earlier this year for the mobile Web. The worry with this system is that it favors established companies that can pay up for speedy delivery of their content, putting smaller firms at a disadvantage and potentially stifling innovation.

"On a tiered Internet controlled by the phone and cable companies, only their own content and services -- or those offered by corporate partners that pony up enough 'protection money' -- will enjoy life in the fast lane," the advocacy group Free Press says.