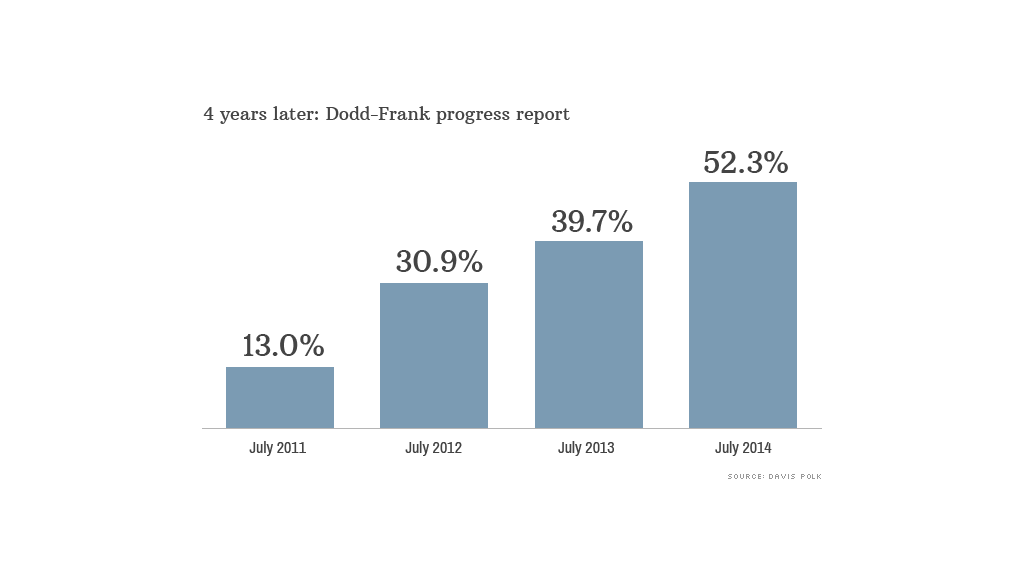

Four years have passed since Congress passed a reform law aimed at limiting the fallout of another Wall Street collapse. Only half of the intended rules are in place.

While regulators have sped up the pace of finalizing the complex batch of regulations required by Dodd-Frank, there's clearly a lot more work ahead.

According to law firm Davis Polk, 208 (52%) of the 398 total rulemaking requirements have been met so far. It's an improvement from 2012, when just 31% of the Dodd-Frank rules were in force, but still lacking.

Missed deadlines: "Progress will ultimately be measured based on whether we have implemented rules that create a strong and effective regulatory framework and stand the test of time under intense scrutiny in rapidly changing financial markets," SEC chair Mary Jo White said in a statement last week.

In the past year, regulators have made progress in a number of areas, including limiting in-house trading activities through the Volcker Rule, reforming the market for complex financial instruments called swaps, cutting back on the reliance for credit ratings firms and creating new rules for municipal advisers.

But it's clear regulators are not exactly moving at lightning speed, at least compared with the timeline set forth by Congress when Dodd-Frank was ushered into law in 2010.

Related: Banks won't lend? Use these guys instead

Out of 280 rulemaking deadlines that have passed, 127 (45%) of them have been missed by regulators, Davis Polk said. That's probably not a track record that your boss would appreciate.

Regulators have fallen behind in a number of key areas that were at the heart of the financial crisis, including asset-backed securities, credit ratings firms, derivatives and mortgage reforms. America is also still awaiting rules tied to consumer protection and the orderly wind-down of financial institutions (think: what to do in case of another Lehman Brothers).

What's the holdup? It's difficult to overhaul the world's largest financial system. That task was made even more complicated by the fact that Congress left many of the tough decisions up to the regulators, since they have more knowledge.

"The burdens that Congress put on regulators through Dodd-Frank are incredibly complex. It's really the largest change to the financial sector's regulation since the Great Depression. So it's going to take a long time," said Gabriel Rosenberg, an associate in Davis Polk's financial institutions group.

Related: 6 events that spooked the markets in 2014

After writing the rules, regulators must give the public a chance to comment on the proposals. Those comments, often from lobbyists representing the financial industry, may result in changes to the proposed rules, which sometimes get watered down.

According to OpenSecrets.org, securities and investment firms such as Goldman Sachs (GS) and JPMorgan Chase (JPM) spent $98 million on lobbying in 2013.

Related: Obama wants more financial reform

"I'd rather the agencies take more time, get more comment and get it right than get it done fast," said Ernie Patrikis, former general counsel at the New York Fed and now a banking partner at White & Case.

"What's the rush? Banks are healing. The economy is healing. We're not going to face a crisis, touch wood, for a little while," he said.

While there has been talk that Dodd-Frank creates extra regulatory uncertainty for the big banks at the center of the new rules, Patrikis doesn't think so.

"If things come in a more orderly way, it's easier to implement," he said.