After decades of losing members, legislative defeats and a declining return on labor, American unions have stopped looking within for the answer.

Now they're looking to you.

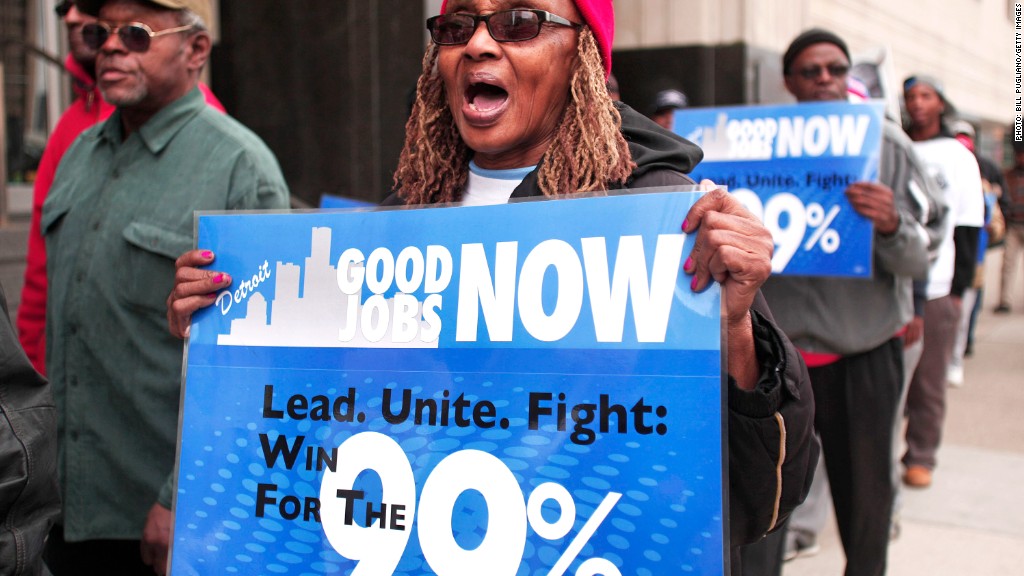

Once focused mostly on the narrow goals of its members, unions of late have sought to spark broader civic movements. Big unions like the SEIU are funding groups like OUR Walmart and Fight for 15, which advocate for workers' rights — though not many Wal-Mart or fast-food workers seem to show up at their demonstrations.

More from Ozy: Me, mom, dad, grandparents all under one roof

Others are taking workers' battles up the supply chain — in some cases, all the way to Wall Street, whose banks they accuse of charging employers predatory fees. And some unions have found creative ways to enlist parents and citizens in their battles, so that when contract negotiations roll around, they're armed with reinforcements and can't be easily labeled as greedy.

Call these methods hacks, call them alt-labor, call them workarounds: They all aim at getting labor out of the corner that it says it's been painted into for the past 40 years.

More from Ozy: Come to the U.S.: Buy a sports arena

"Fixing what's wrong with the labor movement is the responsibility of more than the labor movement and requires the involvement of more than the unions themselves," says Joseph McCartin, a Georgetown historian who directs the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. In May, the Initiative held a conference called Bargaining for the Common Good to discuss ways to open the labor movement beyond employers and employees. Unions actively participated, says McCartin, having "seen that the future for them has to be reaching out to allies and communities, and bargaining differently and in ways that include those allies."

More from Ozy: Extreme food at state fairs

By most accounts, organized labor in the United States has been on the outs for decades. Last week's Supreme Court decision, Harris v. Quinn, chipped away at a cornerstone of union operations — agency fees — and though the decision was narrow, the Court signaled it'd take a wrecking ball to the whole edifice if given the chance. Many in the labor movement had been preparing for worse.

There's no doubt that traditional unions have not kept up with the shifting economy or our politics. For years after the Wagner Act of 1935, which regulated employer-union relationships, most unionists worked in manufacturing. Membership peaked in 1954, at 28.3 percent. Some years later began the long slide of globalization. As factory jobs moved overseas and the American workforce shifted to service-economy jobs, manufacturing lost leverage and unions lost members. Despite pouring millions of dollars into luring new members, the movement never made much of a dent in the service economy.

More from Ozy: Crime that pays well unless you're a woman

Public-sector workers are a different story. Some 35 percent are unionized, and most can't be offshored. Many provide vital services, like home care, trash collection, teaching and policing. In many ways, they're the heart of the union movement, which Harris hurt so much.

It's also one reason that alt-labor considers public unions promising ground: The public has a clearer stake in teachers' working conditions and sanitation workers' wages than, say, auto workers' wages.

Alt-labor won a key victory in February during teacher-contract negotiations in St. Paul, Minnesota, by rallying community members to the teachers' cause and pushing negotiation limits. The teachers' union had spent the previous year on a listening campaign: Think "house parties, book discussions and focus groups" for parents and community members. All those house parties generated a list of demands that went well outside the usual — salary, hours — and into a vision for the school system. The resulting contract hikes teacher salaries, but also invests $6 million in pre-K education; hires 42 professional support staff, like librarians and social workers; limits class size; and reduces class time devoted to standardized testing.

More from Ozy: Come to the U.S.: Buy a sports arena

Such strategies might not work everywhere. They likely breached "management prerogative," a practice that prevents unions from bargaining for much outside wages and hours. But just as important, such demands might be too narrow in appeal. Seeking community involvement and forming qualitative demands are strengths of alt-labor. But they're also liabilities; it's hard to come up with unified demands.

Another alt-labor strategy bargains up the labor supply chain. It's a recognition that "the entitity that decides how much people are going to get paid is rarely the direct employer," says Stephen Lerner, who organized the Justice for Janitors campaign. Employers these days are often middlemen, squeezed and lacking much room to maneuver themselves.

Beginning in the 1980s, Justice for Janitors organized custodians not against their direct employers — cleaning companies — but against the real power players: the building owners who hired the cleaning companies. Like the Mexican crawfish pickers who forced Wal-Mart to sunder ties with their employer, or the Florida tomato pickers who organized a boycott of Taco Bell, such methods try to locate responsibility somewhere.

As supply chains have lengthened, workers are bargaining all the way up to Wall Street. Last week saw the start of what is likely to be a protracted negotiation between Los Angeles and its city employees, including its trash collectors. The trash collectors don't want just a raise; they also want the city to stop paying "predatory fees" to Wall Street bondholders. They've driven circles around City Hall, honking their horns and clanging cowbells.

Citing all this, Lerner refuses to get down about the labor movement. "I am not a member of the union death cult," he says. Unions' best chance of success, he says, is "embracing the notion that acting together is the only way to take on concentrated power — and I'm optimistic, because you see the seeds of this starting to be planted."

Then again, he adds, "people just aren't excited about joining a movement that says there's no hope."