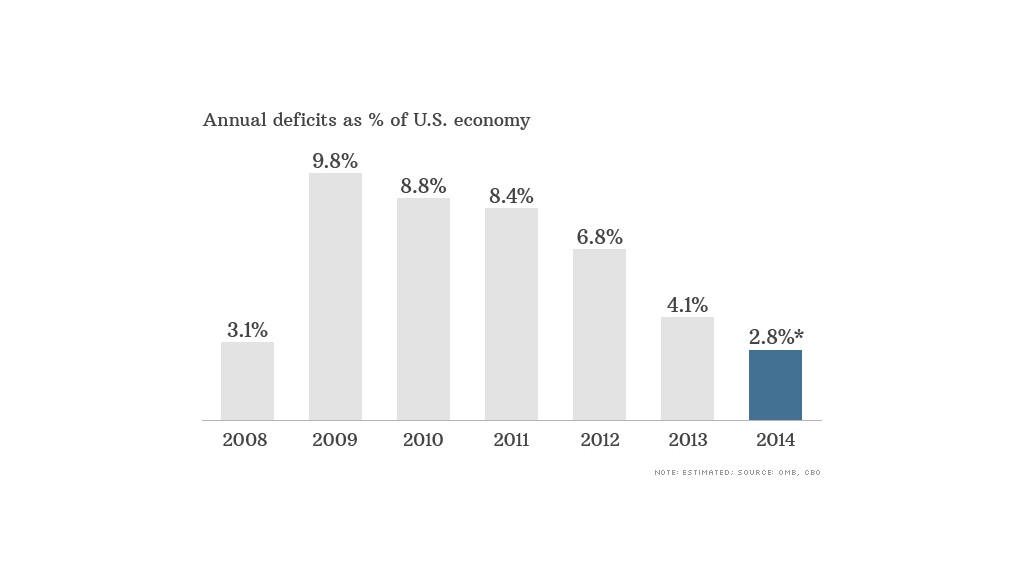

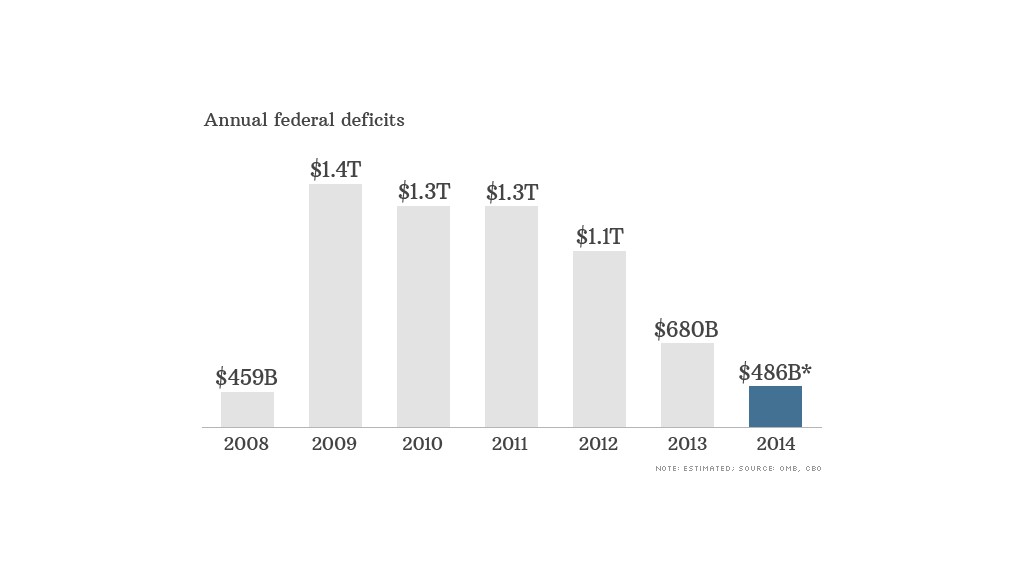

The federal budget deficit just keeps getting smaller.

It fell sharply in 2014 -- its fifth consecutive annual decline.

That's according to an estimate Wednesday by the Congressional Budget Office. The deficit for fiscal year 2014, which ended on Sept. 30, will come in at roughly $486 billion, the CBO said. The Treasury Department will report the official number in a few weeks.

The 2014 number is $195 billion less than a year earlier. And as a share of the economy, the deficit dropped to 2.8% of GDP from 4.1% last year.

The deficit is the gap between how much the government spends and how much it takes in over the year. It borrows to make up the difference.

The biggest reason for the slide: An improving economy, higher taxes, and continued spending restraint.

Revenue grew by 9% over the prior year, or by $239 billion. That growth was fueled largely by a 7% jump in income and payroll tax receipts combined. Corporate tax revenue rose by 18%.

Spending, meanwhile, only grew by 1% over 2013. The bulk of that growth came from mandatory spending, which Congress doesn't vote on annually. Spending on Social Security benefits went up 5% and Medicare spending rose 2.7%. Medicaid spending jumped nearly 14%, primarily because of health reform provisions that went into effect in January 2014.

But the spending increases were largely offset by drops in outlays for defense and some domestic programs.

Defense spending fell by 5%, or $30 billion, while spending by the Department of Housing and Urban Development dropped by 31%, or $18 billion. And unemployment benefits fell by 34%, or $24 billion.

But the days of falling deficits may be numbered.

"Fiscal restraint is falling out of fashion," Greg Valliere, chief political strategist at the Potomac Research Group, noted recently.

For the past few years, lawmakers have only passed spending and tax measures that didn't add to the deficit -- using what's known as budget "pay fors."

Related: Despite dropping deficits, debt picture a concern

But there's a good chance they won't end up paying for the total cost of extending a host of tax breaks by the end of December or replenishing the Highway Trust Fund, among other measures.

Plus, given the swell in geopolitical troubles, lawmakers may want to reverse the budget cuts on tap for defense created by the "sequester," the across-the-board cuts Congress forced on itself. The sequester was never intended to go into effect, since it was only supposed to prod lawmakers to find a smarter, more gradual way to reduce deficits.

Any easing of the sequester for defense could, in turn, "prompt Democrats to demand that [the sequester] be dropped for domestic spending as well," Valliere said.

But even if Congress keeps the spending curbs in place, the CBO has noted previously that annual deficits will start to move up again in a couple of years, and the country's accumulated debt will again start rising faster than the economy.