Reggie Gray thought working for FedEx was his ticket to a better life.

It turned out to be anything but: His years as a driver for FedEx Ground ended with him filing for bankruptcy and taking the company to court.

Gray is one of the thousands of FedEx (FDX) drivers who have sued the company for classifying them as contractors, rather than employees. Many, including Gray, have won.

"We all signed up for what we thought was the American dream," said Gray. "We received the exact opposite. It was a really bad deal."

The FedEx Ground division, created in 2000, delivers small packages to homes and businesses nationwide. But its army of 32,500 uniformed drivers, managers and affiliated workers are classified as contractors, a controversial policy that allows FedEx to save on health benefits, unemployment insurance, retirement accounts and overtime pay, among other things.

"This is an intentional policy on the part of FedEx Ground to deny drivers their rights as employees," said Erin Johansson, research director at Jobs with Justice, a labor rights group.

For Gray, it all started when he left his job in 2002 as a letter carrier with the U.S. Postal Service in Missouri, and signed a contract with FedEx Ground. He thought it would be a great way to start his own independent business with the backing of a major brand.

But Gray quickly realized he wasn't really independent. In fact, FedEx controlled almost all the aspects of his business, even though he had to put up a lot of his own money.

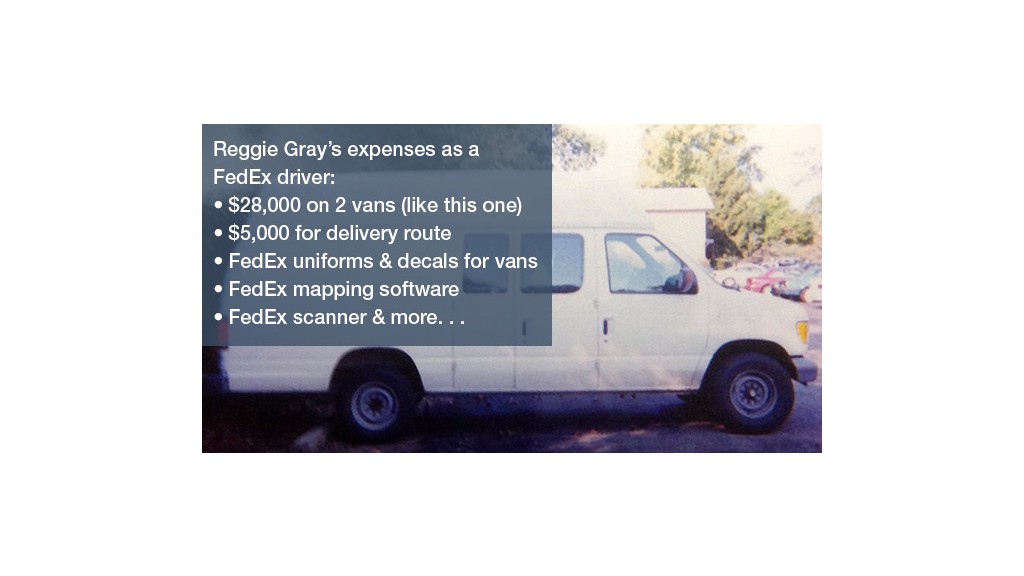

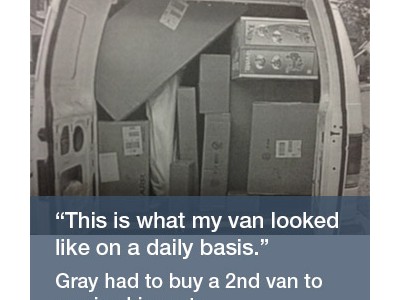

Gray had to purchase his delivery route for $5,000. He bought his own van for $17,000. FedEx later made him to buy another vehicle for $11,000 and hire a second driver when his route got so busy that one van wasn't enough to deliver all the packages. The vehicles needed constant maintenance -- oil changes, brakes, transmission and radiator replacements -- and all came out of his own pocket.

Related: Is your company wrongly classifying you as a contractor? Share your story.

He paid for FedEx uniforms and decals for his vans, company mapping software and also leased a FedEx scanner for the package bar codes. He also had to pay for Department of Transportation inspections and random drug tests the company required.

Gray said FedEx managers in the terminal where he worked hounded him about the condition of the tires on his van and the conduct of a driver he hired to help him with his route.

His supervisors constantly threatened to revoke his contract and docked his pay with inflated "claims" for lost packages. In one case, he said the company charged him $1,600 for a $400 box of vitamins that he failed to deliver.

The debts piled up and Gray was forced to file bankruptcy in 2008. The financial turmoil took a toll on his marriage, which ended in divorce. He almost lost his house.

"This whole ordeal cost me a lot, it really did," said Gray. "Financially, it was a huge, huge hit. And the pressure of that weight was crushing."

The tipping point for Gray came when the IRS reviewed a copy of his contract and told him that he was actually an employee of FedEx, which implied that he was losing out on eligible benefits. He went online and found other drivers in the same situation. After his attempts to work things out with FedEx were unsuccessful, Gray decided to take legal action. (The IRS wouldn't comment on individual cases.)

In 2006, he and a few other drivers filed a lawsuit against FedEx seeking compensation for employee benefits and pay that were denied.

Related: 'My job is super stressful and it pays badly, too'

After several years in court, a jury sided with the drivers this past April. Gray was awarded more than $90,000 in damages.

FedEx said: "We will appeal the court's decision in this case."

FedEx drivers have won some significant legal battles recently. Courts in Oregon, California and Kansas have ruled that FedEx Ground drivers fit the legal definition of an employee. The National Labor Relations Board ruled on September 30 that drivers in Connecticut are FedEx employees. A decision is expected soon from the Seventh Circuit court of appeals, which has jurisdiction over cases in Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin.

The company is currently facing 30 more active lawsuits from former contractors in several states.

FedEx points out that the ruling in Gray's case runs counter to more than 100 other cases where courts have upheld its policy of classifying drivers as independent contractors.

However, that's a fraction of the lawsuits former FedEx contractors have filed against the company, said Catherine Ruckelshaus, general counsel at the National Employment Law Project.

"FedEx actually loses more of these cases than it wins," said Ruckelshaus, who has followed lawsuits against FedEx closely. "But because calling drivers contractors is such a lucrative practice, they keep doing it."

FedEx disputes that it has lost more cases than it has won, and stands by its employment policy.

Related: Part-time jobs put millions in poverty or close to it

Under pressure from Attorneys General in several U.S. states, FedEx Ground changed its policy in 2011. The drivers are still not FedEx employees. But the company now contracts with incorporated businesses that agree to treat staff as employees. That way, drivers get basic protections required by law such as workers compensation coverage and unemployment insurance. But again it's the contractor that provides those protections, not FedEx Ground.

FedEx's policy is in stark contrast with its main rival. UPS classifies all of its drivers as employees. As members of the Teamsters Union, UPS (UPS) drivers have significant bargaining power.

FedEx recently started tracking how much cash its contractors generate. The company says the average business with about four drivers each brings in $443,000 a year in revenue.

Related: Why I have a roommate at my age

Gray's route, which he worked with one additional driver, brought in far less.

Before taxes and expenses, Gray said he brought in between $50,000 and $70,000 per year. After paying all his dues, insurance and the other driver, Gray's net income ranged between $25,000 and $35,000 per year. At that rate, Gray was earning roughly minimum wage while putting in 12 to 16 hour days.

The court's decision for Gray has been a hard-won battle, even though it's stuck once more in FedEx appeals limbo.

"The men and women in that terminal made this company millions and millions of dollars," said Gray, 44, who is now back working for the postal service as a letter carrier. "For this company to knowingly and willingly do this to us -- it's wrong."