The Los Angeles police chief is asking Google to eliminate a cop-spotting feature from its Waze traffic app.

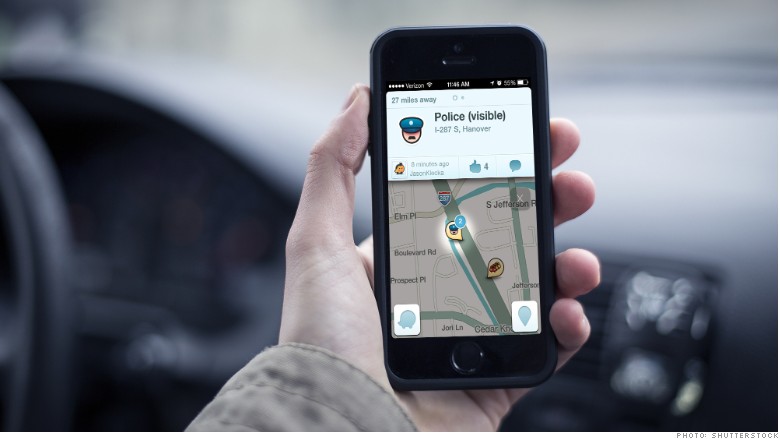

Waze is Google's (GOOGL) popular traffic app that lets users collaborate to report locations of heavy traffic, road closures, police speed traps and other driving incidents.

Publicly sharing information about the location of a marked police car, the LAPD chief claims, jeopardizes police officers' lives.

His evidence? The man who recently killed two cops in New York had used the Waze app at some point before the shooting. The shooter, Ismaaiyl Brinsley had posted screenshots of it on his since-deleted Instagram page.

In a Dec. 30 letter, LAPD Police Chief Charlie Beck cited last month's killings and told Google CEO Larry Page, "Your company's 'Waze' app... poses a danger to the lives of police officers in the United States."

Now Waze is answering back, saying that it actually operates with support from law enforcement.

"Police partners support Waze and its features, including reports of police presence, because most users tend to drive more carefully when they believe law enforcement is nearby," Waze spokeswoman Julie Mossler said in a statement.

CNNMoney asked the LAPD chief why the location of uniformed officers and marked police vehicles should remain secret, but he hasn't yet responded.

At the heart of the issue, though, is a question America is wrestling with today: To what extent can the public monitor the police?

There's an increased pressure for police monitoring, given the recent unprosecuted incidents of police violence -- from the shooting of teenager Michael Brown to the slow, death choke of Eric Garner.

In recent years, citizens have started arming themselves with cameras and filming police encounters. And while the public has an established right to videotape police in public, officers have repeatedly fought back by confiscating cameras and making arrests for charges that are later dismissed.

Waze plays a role in that. The nationwide volunteer police monitoring group Cop Block, for instance, uses it to spot police locations so they know where to go with their cameras. Its founder, Adam Mueller, remembers using it a few months ago in his hometown of Keene, New Hampshire.

But it's not always accurate. Waze is based on user-submitted data, which is often old and sometimes unverified. If a police car is on the move, that data is useless seconds later. That's why Waze isn't the dangerous cop-tracking tool it's made out to be.

And even if it is accurate, Mueller thinks people have every reason to share police locations on Waze.

"They're in clearly marked cars," Mueller said. "They're public officials conducting a public duty in a public space. There's no expectation of privacy."

To that extent, Waze is little different from the old trick of flashing your headlights to warn oncoming drivers of a police car. Or the niche hobby of listening to publicly-broadcast police radio traffic.

Carlos Miller, who aggressively advocates for police-monitoring and runs the Photography Is Not A Crime blog, thinks Waze is just the natural public response to all of the advanced ways police have been surveilling Americans in recent years, from a facial recognition database to using planes to spy on phones.

"We finally got the technology to watch them back, and they don't like that," Miller said.

Related: China crackdown makes it harder to get around the Great Firewall