Despite all the hype, Bitcoin isn't anonymous. It's electronic cash. And like anything digital, it leaves a trail of bits.

The latest example? The guilty verdict in the trial of Ross Ulbricht, the kingpin behind the online drug bazaar Silk Road.

His attorney took a stunningly odd approach to his defense: Yes, Ulbricht ran the site. Yes, those millions of dollars in bitcoins are his. But he stopped running Silk Road a long time ago.

Here's why that logic didn't work: Federal prosecutors showed that millions of dollars in Bitcoin payments were traced from Silk Road back to Ulbricht's personal laptop -- until just before his arrest.

How was that possible? Here's a mini crash course in Bitcoin.

Bitcoin is all about electronic wallets that send digital cash directly to one another. All you need is a Bitcoin wallet address. You never need to know someone's real name. And at the center of it all is the engine that keeps the system alive: a public record of all transactions called "the blockchain."

It seems anonymous at first -- but only if you keep your wallet address secret. If that's connected to your name, the whole world knows every transaction you've ever made.

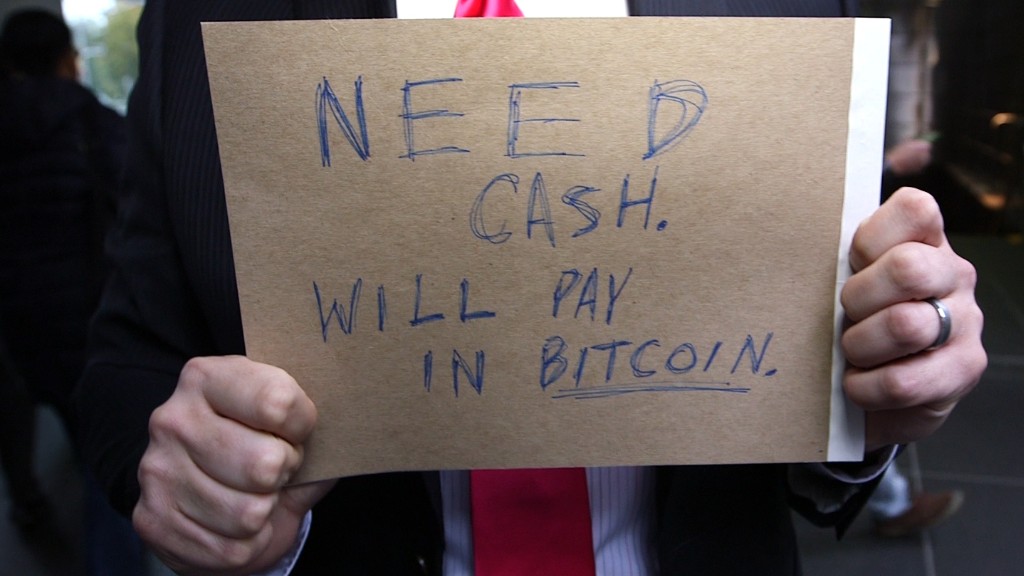

That's why Bitcoin's notoriety as the tech-savvy criminal's currency of choice is absolute lunacy. Bitcoins track everything. Some Bitcoin users have even taken to calling them "prosecution futures."

In Ulbricht's case, it all came down to what happened in a New York federal court on January 29.

That was the day jurors heard testimony from Ilhwan Yum, the FBI agent who examined the Silk Road website's computer servers in Iceland and Ulbricht's confiscated laptop. He cross-referenced Bitcoin wallet addresses found in each computer to the blockchain itself -- and voilà.

From September 2012 until August 2013, Ulbricht's personal laptop received 3,760 transactions from the Silk Road worth 700,254 bitcoins, the FBI agent said. That means Ulbricht had received the equivalent of $18 million over that time.

"I didn't do any complicated analysis," Yum said in court, noting that the publicly available blockchain records made it even easier to figure out than if a criminal had used a legitimate bank. At least that takes a subpoena.

The numbers also showed that 89% of the bitcoins that made it to Ulbricht's laptop came straight from the online black market. That didn't jibe with his defense attorney's story that they all came from his Bitcoin trading.

Ulbricht's lawyer, Joshua Dratel, protested that he was blindsided by this in-depth FBI analysis of Bitcoin wallets and transfers. But it was too late. He should have known, U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest said. Outside security researchers, like Stanford's Nicholas Weaver, had already determined that a sizable portion of Ulbricht's Bitcoin stash came from Silk Road.

As computer scientist Sarah Meiklejohn warned last year, "Every Bitcoin is by nature a marked bill. All that's required is putting together some pieces."

That's why Ulbricht's trial is so curious. It's among the first times that truly electronic money played a major role in determining someone's role in a crime. The jury found Ulbricht guilty on all seven counts related to money laundering, hacking, trafficking forged identities and distributing narcotics.

And Ulbricht's defense -- saying he actually owned the bitcoins -- made it so easy that U.S. prosecutors told CNNMoney they were flabbergasted (before the verdict was even out).

Think of what federal prosecutor Timothy Howard told the judge in court last week.

"At the end of the day, it is all based on public records showing one-to-one connections between Bitcoin addresses. It is not anything very complicated," he said.

Now that should make criminals think twice.

Jose Pagliery is the author of Bitcoin - And the Future of Money (Triumph Books, Chicago).